Where the Wild Things Are Familiar Again

Photographer Sam Hobson uses urban wildlife to connect people to the natural world

Photos by Sam Hobson

Sam Hobson often spends his nights hunting around alleyways and behind bushes and drainpipes, looking for urban wildlife. But when it came to a pair of migrating common toads? “They were literally on my doorstep,” he says.

Hobson is a professional wildlife photographer in the UK who specializes in documenting the creatures big and small that make their home in our concrete jungles. He grew up in London and is now based in Bristol; at an early age, he was fascinated by the animals right outside his front door. Today, Hobson is at the vanguard of a new enthusiasm in photography he helped popularize for professionals and shutterbugs alike: to explore and document the urban wild.

Hobson spends days, sometimes even weeks, researching and tracking animals through city streets—identifying their nesting sites, hunting grounds, and nocturnal routes, and marking prime locations for photographing them. He often employs an unconventional method for lighting and photographing creaturely life. For the toad series, he lit them not with flash but a constant torch light that is more commonly used by wedding photographers. “Because toads tend to stop dead still for a couple of minutes at a time,” he said in an interview, “you can shoot a long exposure and light them that way. You don’t need to use flash. I use a constant torch light that is color balanced with the city lights so that the toads are lit more naturally.”

He photographed the toads with a Sigma 15mm f/2.8 lens, which he favors for its close focusing distance. “You can literally be within a couple of centimeters of the subject and still get it sharp in the camera,” he says. “If you’re using a wide lens, it just means you can make what’s in the foreground nice and big and punchy and exciting if you get close enough, and still get tons of background. For me, it’s all about capturing the context—using the environment to tell a story.”

The locations for his shots are just as carefully thought through as the animals he photographs. For city-dwellers, wildlife is often liminal, experienced on the margins as something distinct and apart—either in controlled environments like zoos or parks, or in ephemeral moments early in the morning or late at night. Hobson wants to reconnect us with the centrality of the natural world by presenting it in familiar scenes of everyday city life.

“If you take a picture of an animal out in the middle of a field or in a tree, it’s got no connection for a lot of people,” he says. “Nature lovers like it obviously, but to the average person on the street, it could mean nothing to them. If you show that person any animal in front of something mundane, like a bus stop similar to the one where they sat every morning for the last several months, only in this picture there’s a big deer stag standing right there, it can spark something. They could think, ‘Oh wow, that deer could’ve been at my bus stop just a half hour ago.’ That’s why I do it: to reach those people; to use urban wildlife as a gateway to getting them thinking more about the natural world and wildlife in general.”

For most of his urban shoots, Hobson favors a weathered but trustworthy Nikon 17-35mm f/2.8— the same lens he used to shoot a stunning series of wide-angle close-up shots of wild urban foxes roaming around Bristol late at night. The lens’ autofocus is broken; he hasn’t gotten it fixed because he prefers not to use it anyway. Hobson likes to set his focus manually and wait for the animal to come into the right place. “I set up my lights, my focus, my exposure, everything before I take the shot, and wait for the animal to come to me,” he says. He’ll often take photographs remotely with a PocketWizard remote release.

Hunting down small creatures in the middle of a big city is an exercise in extreme patience. Hobson spends the least amount of time taking pictures and most of his time planning excursions, and then roaming around, from the environs to the heart of the city, and just noticing things. Often, he won’t even take a camera with him, focusing instead on documenting locations and backgrounds, taking note of areas with nice composition. He’ll then look around for tracks or other signs of animals. If it’s a certain time of year, when there is a lot of brush or grass everywhere, he may note the area as one to revisit in the winter, when the terrain will be flatter and better for pictures. Or he might take note of a bush he knows is good for certain types of berries located in an area with a good background, then come back in the summer when it has berries, and typically, he’ll find that there are birds there, or he’ll return in the spring when there are flowers and insects.

Sometimes he uses a trail camera, like a Bushnell. If he sees animal tracks somewhere, he’ll leave the camera on the trail to get time-stamped stills and video clips or images of what was walking past. It’s usually rats and neighborhood cats, but sometimes it can be something more interesting.

“It’s all about keeping your eyes peeled and trying to tune into nature,” he says. “That’s one thing you forget while living in the city: that there is a lot of wildlife around. If you have your blinkers up, you don’t notice it. But there are little things you can do to start paying more attention. If you learn the most common bird song, like five or six of the most common types you’re likely to hear in your own backyard, then when you hear one you don’t recognize, you know it’s potentially an interesting bird or maybe a migrating bird, and you can try to identify it.”

Sometimes, it’s the chance encounter he wasn’t expecting that has led to some of Hobson’s best work. More often—as in a series on rose-ringed/ring-necked parakeets in flight toward a roosting ground in a London cemetery—he maneuvers himself into precisely the right time and place through a meticulous methodology of scouting and planning.

His series on deer in London is one of the best examples. Urban foxes can be bold, but deer are fairly shy and flighty, and typically stick to the woods. While in the UK countryside, it might be typical to see deer on the side of the road, not so much in a big city like London. Hobson was determined to track them down.

The project started as many of his do: by speaking with locals. “There are certain types of people you can talk with that are gold mines of information,” he says. “If you speak to people that keep unusual hours, like night watchmen, security guards, or bus drivers who work the night shift, or people cleaning up the streets early in the morning, you often find out where the wildlife is in the city.” To find the deer, Hobson spoke to several night bus drivers who cover a lot of ground in London, and then established a stakeout at a hotel.

When he finally found them, Hobson was stunned. “Seeing a fully grown buck in somebody’s front yard eating their flowers was quite crazy,” he says.

Photographing the deer was a challenge: The animals tend to move in small packs and are very timid. On his first two nights, the deer ran off as soon as they saw Hobson coming, which produced only a series of hazy stills of dear rear ends. It took him a few more nights to map out their territory and identify where they came out of the woodlands and into the streets, and what their typical routine was. He was eventually able to anticipate the pattern, and then hid in his car, waiting for them to come to him.

This tactic can lead to stickier problems, such as how the occasional passersby react to the optics of the whole thing—i.e., of him. After all, the sight of a grizzled young man in a parka with the hood pulled over his head sticking a long camera lens out a car window on a city street late at night could be, let’s just say, a tad discomfiting. “You get the odd person coming up to you either thinking you’re a peeping Tom, or that some celebrity like Kim Kardashian is walking about,” he says. “But as soon as you say, ‘Oh, I’m trying to find these deer. I hear there’s deer around here,’ then often you get these guys who light up and say, ‘Oh yeah! Just go right around the corner; there’s loads of them down that way.’ I’ve never had bad encounters where things didn’t turn out for the better. All I had to do is tell people what I was doing and why."

“What I have found in my time shooting urban wildlife is that everybody’s got a story,” Hobson says. “You can literally stop anybody in the street and speak to them about wildlife, and they will have a story about growing up with foxes in their grandmother’s garden, or going home from work every day and seeing these amazing birds in the trees. I think it’s because it brightens up people’s day a little bit. You can get stuck in a mundane cycle of every day doing the same thing. But when you see a bit of wildlife, it’s a bit of excitement on your walk home.”

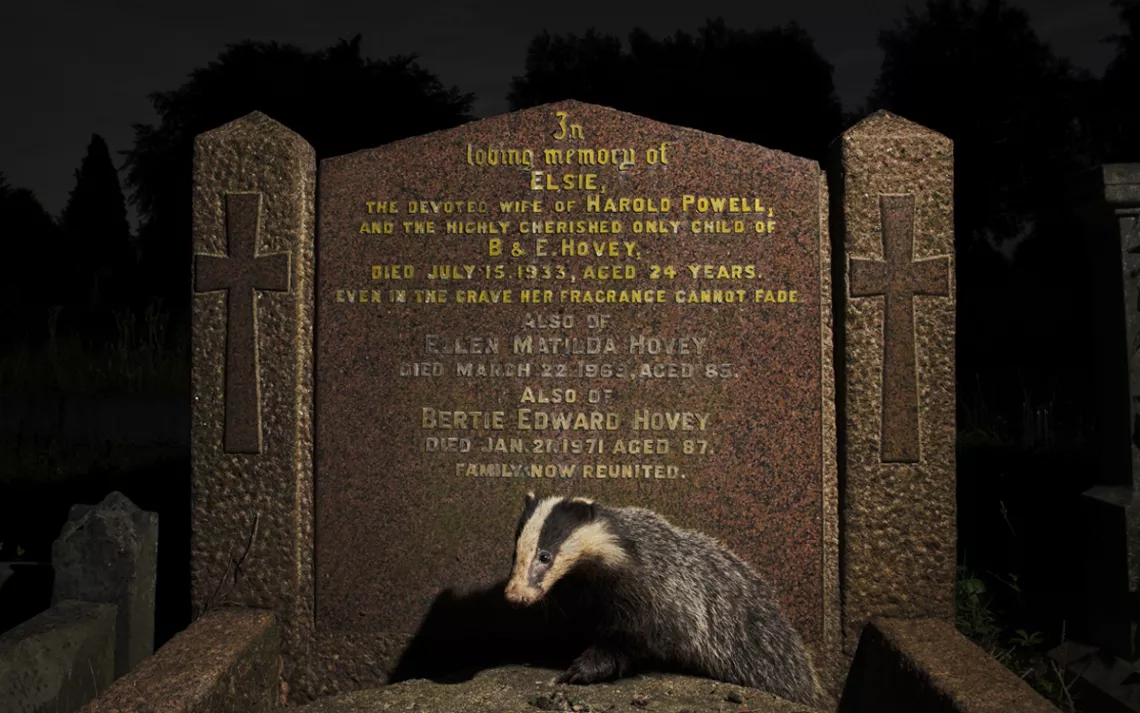

Photographing urban wildlife is an exercise in learning how to better see our planet’s small and fleeting wonders. The annual migration of small peripatetic creatures like warblers and toads can send some animals through city streets that have been traveling for miles. Meanwhile, along with those all-too-human neighbors across the street are the badgers, foxes, and goshawks that share with us the avenues and rooftops of a city’s byzantine metropolitan backcountry.

It’s one of the great ironies of city life: While chance encounters with the natural world in urban settings often excite us, rarely do we take the time to pay attention to how that world and its creaturely life are central to who, and what, we are. Through photography, Sam Hobson is out to shake us loose from the fugue of our everyday conceit, and give us a little nudge out the door. “The whole reason I do it, apart from the fact that this is where I come from and live, is human engagement,” he says. “It’s about reaching those people that are perhaps a little bit disconnected from nature by showing them something in a familiar context."

“People need that reminder that these wonderful natural things are still happening out there,” he says. “Especially now, with all the negative stuff going on in the world. The world would be a much more depressing place without the potential of having a chance encounter with the wild. Even if it’s just during a walk in the park.”

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club