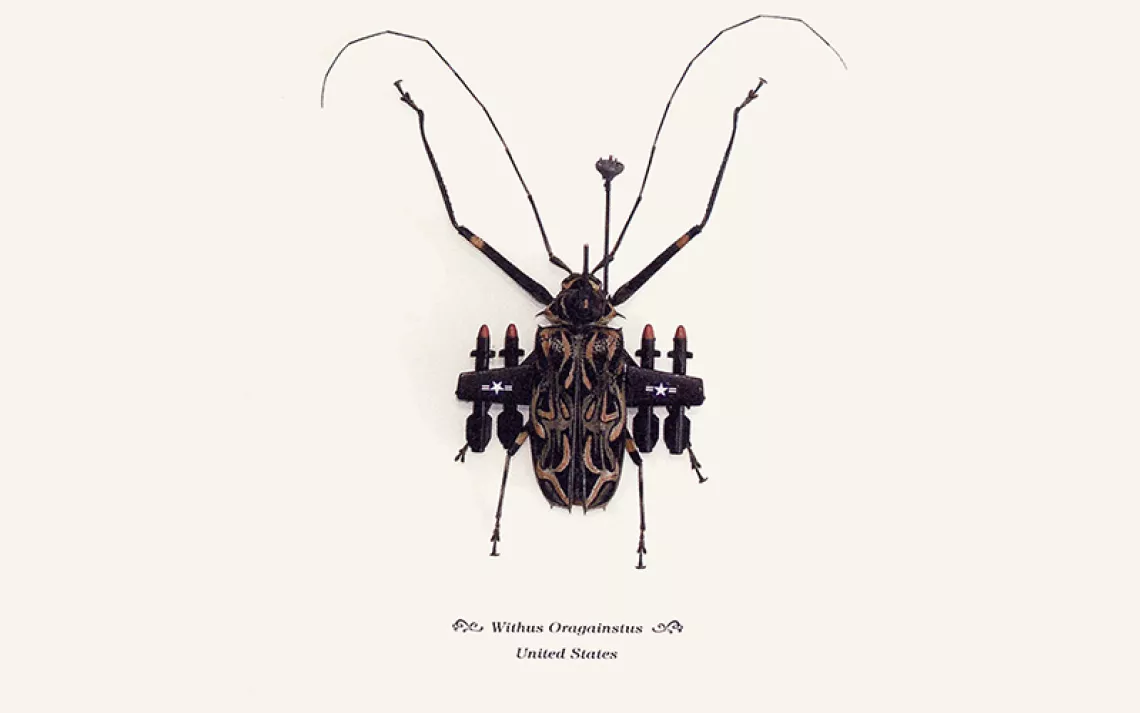

Turning Junk Into Art, and Making Anything Possible

Patrick Amiot turns found objects into art and neighborhoods into magical places

Photo by Michael Shapiro

California artist Patrick Amiot stumbled across an old aluminum boat for $40 at a flea market one day, thinking he might turn it into a giant African mask. The boat languished outside the house for a few weeks until Amiot’s wife suggested he clean up the driveway.

“That’s when I came up with the idea of making a giant fisherman,” Amiot said recently in an interview. “That was the very first piece [of junk art]: The body was made with the old rowboat; the head was made with a wheelbarrow and a Weber barbecue. And he’s holding a fish that was made with a drop tank.” He noted that drop tanks were World War II containers used by fighter planes to carry extra fuel—after missions, the planes would drop the tanks in the ocean. “So after the war, they were scattered everywhere throughout the Pacific,” Amiot said. “There are still thousands of them available. It looks like a giant torpedo—I made the fish out of that.”

He put the fisherman in front of his house, in the town of Sebastopol, about 50 miles north of San Francisco, in May 2001. “I thought the city would tell me to take it down,” he said. But the eco-minded city council, then with a majority of Green Party members, was as thrilled as most of Amiot’s neighbors were with the 15-foot-high artwork that graced Florence Avenue, a couple of blocks west of downtown. Amiot felt he was “threatening the landscape." But, he said, "On the other hand, I was recycling. It was, ‘Yeah, he’s over-the-top, but he’s recycling.’”

He’s been turning junk into art ever since.

Amiot, 57, relishes how every object tells a story, and that’s part of the appeal of his whimsical art. Those who view his figures—which range from Batman to Babe Ruth, from mermaids to the Mad Hatter—love the challenge of trying to figure out the origin story for the different objects that compose each artwork.

After the Twin Towers fell on September 11, Amiot made a firefighter from discarded material, installed the figure on a box painted with American flags and put it in a yard across the street. Neighbors loved what they saw and invited Amiot to put a piece of his art in their yards.

Soon curious onlookeers were driving to Sebastopol to see Amiot’s whimsical creations.

Left: Patrick Amiot’s “Babe Ruth” on Florence Avenue in Sebastopol, Calif.; Right: Patrick Amiot’s “Batman” on Florence Avenue in Sebastopol, Calif. Photos by Michael Shapiro.

He calls it a “people’s gallery” because visitors can come any time they like—many artworks have lights shining on them at night—and unlike most musuems, there’s no admission fee.

Amiot’s wife, the wildly creative Brigitte Laurent, paints the artworks. Amiot said his wife deserves as much credit as he does for making the art so appealing, that she has buoyed him up when times were tough and always encourages him to challenge himself and take risks.

Their next project is to go to a place like Norway, see what they can scavenge in a week, then spend the next week making a monumental piece of art that fits with the country’s sensibility.

“Even though it’s not my first idea of fun,” Amiot said, “it would be a better challenge for me than any other because it would force me to go back to my roots. There’s something very magical that happens when you let your emotions free.”

Laurent immediately added, “I’m all for it!”

Her support goes far beyond art: Laurent has been Amiot’s co-conspirator in risk-taking for more than 30 years and supported the move from Montreal to the United States 20 years ago, arriving in Sebastopol on August 5, 1997, with their two young daughters (five and seven at the time).

Amiot had made a living in Canada creating ceramic figures, mostly of hockey players, but by 1997 wanted to do something different. That’s when he and the family landed in Northern California.

By the early 2000s, Amiot had made several more artworks and put them in neighbors’ yards, but he never thought about selling these artworks. Then a neighbor, a college professor named Rene Peron, called him and said he had some stuff to give him.

“So I picked up all of his stuff and made a vow to transform it into something for him,” Amiot recounted. “When his wife saw the pickup truck, with a cow in the back, that I made out of all the stuff he’d given me, she bought it. Isn’t that amazing? One day this guy calls because he wants you to pick up the shit that he’s put by the road—tin cans and drums and garbage cans—and another day he buys it and puts it in front of his house and lights it up and glorifies it.”

Amiot said it’s recycling in every aspect. “I recycled his thinking, because he went from seeing something that you didn’t care about to all of a sudden really caring and loving it.” The truck with the cow remains one of the star attractions of Florence Avenue. Peron’s truck “is his baby,” Amiot said. “Rene would always stand next to his piece when tourists were there—he loved to engage them.”

Photo courtesy of Patrick Amiot

Soon other neighbors wanted their castoffs to become part of Amiot’s art. “When I came to California, I didn’t know the word ‘hoarder,’” he said. “Some woman called me and said her father was a hoarder—all I could think about was sheep.”

The woman’s father had a barn full of [car] taillights and hubcaps from the 1940s. “Hoarders usually don’t let go, but this guy was dying of cancer,” Amiot said. The daughter told Amiot it was very important for her to see him use this stuff. “She said to me later that every time she drove up and down the street, she could feel her father’s spirit—there were all these taillights that I used to make eyeballs. I felt like I was really fulfilling my job because I was recycling, I was helping this woman get rid of something, and the dad felt like in a way he’d become immortal.”

Soon Amiot and Laurent were doing what they couldn’t imagine when they moved to California: making a living turning junk into art. Even as their reputation grew, they continued to give back to the community—donating a great-horned owl to a local school, fashioning a towering cat for the Sebastopol Police Department that urges motorists to slow down for safety, and creating an annual calendar to raise money for local schools.

In 2012, a Canadian developer approached Amiot seeking a piece of his art for a new project near Toronto. Amiot suggested an installation much more ambitious than anything the developer could conceive: a functioning carousel with 44 of his junk-art sculptures. Called The Pride of Canada, it was built in Sebastopol, then shipped to the Toronto suburb of Markham, where it’s been delighting kids—and their parents—since its first spin last summer.

Amiot and Laurent hope their message is about more than turning junk into art and reducing the amount of waste going into landfills. They hope their work demonstrates how a neighborhood can be a “magical place” where kids grow up thinking anything is possible.

“All of a sudden, it’s normal to have something big, bold, and crazy in front of your house. That to me is way more important than anything else,” Amiot said. “In mainstream America, you don’t see giant sculptures in front of people’s houses, but if you’re brought up in this community, it’s a natural thing. These people grow up thinking it’s alright to show your colors and do wild and crazy things. And it just so happens that the things they saw were actually made out of recycled materials.”

Amiot remains modest, saying he doesn’t have the skills of many accomplished artists. “I’ve met people who are way better than me technically. But Brigitte and I were gamblers. We were willing to take chances.”

Laurent added, “We followed our hearts in easy and rough times.”

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club