Dominion Energy and Duke Energy Corporation plan to build three massive compressor stations along the Atlantic Coast Pipeline’s 604-mile route — including one in Union Hill, a historic African-American community in Virginia founded by freed slaves after the Civil War. Designed to keep the fracked gas flowing in the pipeline, the 54,000-horsepower facility would also expose local residents to constant noise and hundreds of tons of harmful air pollution each year — including pollutants that exacerbate asthma and increase the risk of lung cancer.

Union Hill residents have spent years fighting the corporations’ plan to build this dangerous industrial facility in their community. Last August, Virginia’s Advisory Council on Environmental Justice – established to provide advice to the governor – cautioned that the compressor station “could be perceived as exhibiting racism in siting, zoning, and permitting decisions and public health risk.” (Research indicates that companies tend to site facilities that threaten human health in communities of color and low-income communities because they often lack the political clout and resources needed to fight siting decisions.)

In January, the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality and the State Air Pollution Control Board nonetheless approved an air permit for the compressor station—after Governor Northam abruptly removed two Board members who had expressed concerns about siting it in Union Hill. Two local groups promptly filed an appeal in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit challenging the permit.

In June, several civil rights and faith-based groups joined the Sierra Club in filing a “friend of the court” brief in support of that challenge. These groups include Union Grove Missionary Baptist Church, Virginia State Conference NAACP, Virginia Interfaith Power & Light, and the Kairos Center for Religions, Rights, and Social Justice.

Siting the polluting compressor station in the predominantly African-American community of Union Hill is a textbook example of environmental injustice. The brief highlights the state agencies’ misguided attempts to evade that plain reality:

-

The state agencies relied on census-based analyses that obscured the very existence of the African-American community in Union Hill. Because the compressor station site is located in a large census tract that is majority white, census-based tools grossly underestimated the percentage of people of color living near the compressor station (where health risks would be concentrated). For example, one census-based tool estimated that the population living within a mile of the compressor station is 29% minority. But a comprehensive door-to-door survey showed that more than 83% of the community members residing within a 1.1-mile radius of the site are people of color.

This discrepancy is precisely why the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s guidance on environmental justice warns that “pockets of minority or low-income communities… may be missed in a traditional census tract-based analysis.” Yet the state agencies inexplicably continued to afford great weight to the census-based results even after they were invalidated by local demographic data showing the actual make-up of the surrounding community.

-

The state agencies relied on the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission’s (FERC) arbitrary environmental justice analysis, which utilized a flawed methodology seemingly designed to avoid the on-the-ground reality that the compressor station would be located in a predominantly African-American community. The Sierra Club and other groups are separately challenging FERC’s approval of the Atlantic Coast Pipeline. (This is not the first time that the Sierra Club and its partners have challenged FERC’s disturbing pattern of cherry-picking data to conceal that a new polluting facility would be located in a community of color. In 2016, for example, FERC insisted that a compressor station in Albany, Georgia would not be located in an environmental justice community because the census tract is majority white—conveniently ignoring that 82% of the residents within a one-mile radius of the site are African-American.)

-

It is the policy of the Commonwealth to ensure that new energy facilities do not have a “disproportionate adverse impact on … minority communities.” But the state agencies adopted the untenable position that only a proposed energy facility that would violate air quality standards—that is, a proposed facility that would not receive a permit in the first place—can have a disproportionate impact on environmental justice communities. This nonsensical approach ignores that the compressor station would emit more than 30 toxic air pollutants, as well as pollutants such as fine particulate matter that have no known safe exposure level—and that the adverse health impacts would fall squarely on the predominantly African-American community living near the compressor station.

As a result of these errors, the state agencies approved the air permit without ever grappling with the environmental injustice of locating the compressor station in Union Hill. The Fourth Circuit has already blocked several agency approvals for this unnecessary pipeline, and the air permit for the compressor station deserves the same fate.

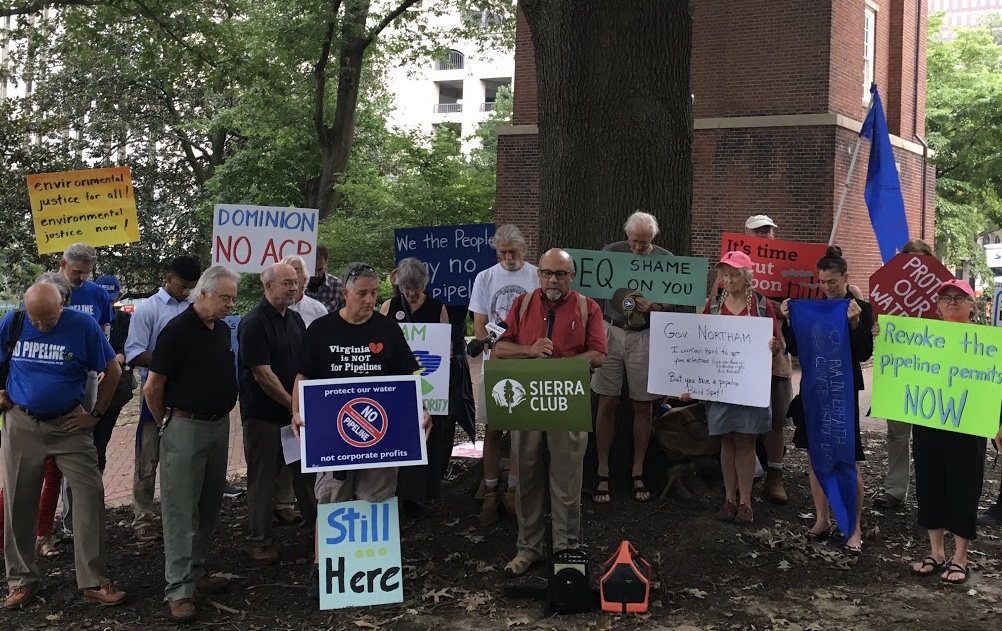

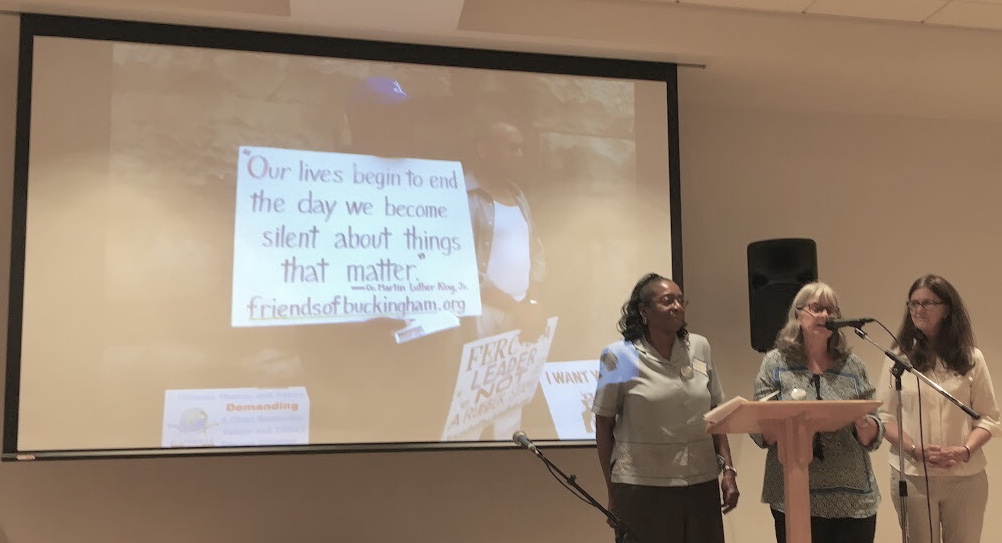

Union Hill residents Ella Rose and Chad Oba, along with Dr. Lakshmi Fjord, speak at the “Rally For Our Planet: No To Pipelines!” event last September (photo by William Davies).