The Science of Awe

Can psychologists chart what happens when nature blows your mind?

Cedar Wright enjoy a view of the long way down, moments after getting the first ascent of the Virgin Tower in Enshi Grand Canyon National Park, China. | Photo by Keith Ladzinski

A FEW YEARS AGO, I RAN Utah’s Green River with a group of 13-year-olds. Our first day was a grueling, 26-mile slog through mostly flat water, with a few Class I and II rapids as our prize. I knew the real reward would come when we entered the most majestic part of Desolation Canyon in a couple of days, but they wouldn’t take my word for it. They were slouched in their boats asking, “Why are we doing this?”

That evening a thunderstorm rolled into the river valley, and we spent an hour in our tents. It was one of the most intense and otherworldly storms I’d ever seen. When thunder struck, it felt like my body was inside God’s clap, and the lightning galvanized the entire sky. Eventually the sky cleared. I stepped out of my tent as if exiting a bomb shelter, with a distinct feeling that the world would be different. The kids seemed to emerge from their tents at the exact same instant. The air was heavy and hot, the sky a color I had never imagined—gold from the land to the firmament. Time slowed. The mountains, the people, and the river flowing through it all seemed held together by an intelligent pattern.

The frustration of the day’s paddle was wiped away. I felt benevolent and open toward the kids. Making dinner was easy. The storm had pulled us together.

Looking back, I was puzzled by the experience. What had happened to me during that thunderstorm? I know humans don’t move in unison accidentally, so why did I think we’d emerged from our tents in perfect sync? I’m not a spiritual person, or a gushy one, so what caused this quasi-religious feeling that the mountains, people, and river were hanging together in ethereal balance?

I am both thrilled and dispirited to report that science has answered these questions.

Scientifically speaking, the storm brought me into a state of awe, an emotion that, psychologists are coming to understand, can have profoundly positive effects on people. It happens when people encounter a vast and unexpected stimulus, something that makes them feel small and forces them to revise their mental models of what’s possible in the world. In its wake, people act more generously and ethically, think more critically when encountering persuasive stimuli, like arguments or advertisements, and often feel a deeper connection to others and the world in general. Awe prompts people to redirect concern away from the self and toward everything else. And about three-quarters of the time, it’s elicited by nature.

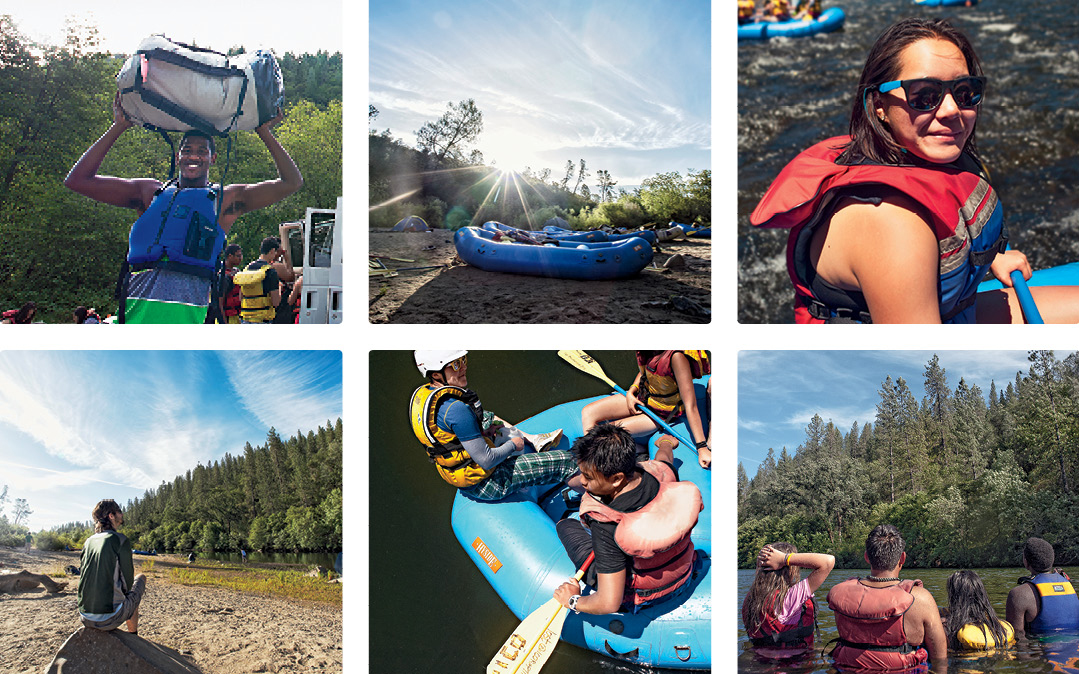

In June 2014, the Sierra Club’s Inspiring Connections Outdoors program (formerly known as Inner City Outings) arranged to take 25 Oakland High School students on a two-day rafting trip down Northern California’s American River. They also took part in a study designed to quantify the biological and emotional benefits of such a trip. | Photos by Jayms Ramirez

IT WAS ONLY 11 YEARS AGO that psychologists Dacher Keltner of the University of California, Berkeley, and Jonathan Haidt, then at the University of Virginia, proposed awe as an emotion worth studying. “In the upper reaches of pleasure and on the boundary of fear,” they wrote in the journal Cognition and Emotion in 2003, “awe is felt about diverse events and objects, from waterfalls to childbirth to scenes of devastation. . .Fleeting and rare, experiences of awe can change the course of a life in profound and permanent ways.”

Over twenty studies later, the picture of awe is clearer and more detailed. “In various studies we’ve asked people, ‘What’s running through your mind when you feel awe?’” Keltner said, “and they’ll say things like ‘I want to make the world better,’ or ‘I just feel like being quiet,’ or ‘I feel like purifying things.’ It makes you humble. It makes you curious about the world.” To awe, Keltner attributes both the faith of Krishna, who, according to myth, on being shown the secrets of the universe through a third eye, was suddenly ready to do God’s work; and the desire of John Muir to protect the environment, which was brought about by his life-altering experiences in the Sierra. Throughout his writings, Muir described quintessential awe experiences. Take this moment, when he feels pleasurably energized by the massive and threatening Mt. Hood: “There stood Mount Hood in all the glory of the alpenglow, looming immensely high, beaming with intelligence, and so impressive that one was overawed as if suddenly brought before some superior being newly arrived from the sky.”

Not surprisingly, such experiences are tough to replicate in a laboratory setting. To elicit and study awe, Keltner and his peers instead rely on mind-bending videos, quick exposures to nature amid urbanized landscapes, or vast and disorienting stimuli. In an early study, participants were asked to stare at a replica of a T. rex skeleton. These techniques work. Psychologists can show certain awe-inducing videos to a test group and then ask questions about how cognition, other emotions, and self-concept are affected by the experience.

However, Keltner, a tan Californian with sandy, shoulder-length hair and a wholesome smile—who cites hiking in the High Sierra, meeting the Dalai Lama, and the births of his daughters as among the greatest awe events in his life—thinks scientists can gain a new perspective on the emotion if they move away from amazing-video, dinosaur-skeleton awe. To conduct what Keltner believes will be the first study to measure the long-term, physical health benefits of awe, he and a team of grad students are moving the laboratory into the woods.

“The science of emotion gets really exciting when you get as close to the phenomenon as possible,” Keltner told me. “We want to engage with people and observe them when they’re really out there on the river or lying under the stars.”

WHICH IS WHY I FIND MYSELF pulling into an eddy on California’s American River with a boatload of students from Oakland High School and their environmental science teacher and guide, Kevin Jordan. A hundred yards ahead, the water drops at a commotion of river and rocks called Troublemaker. It churns with whitewater and white noise. The kids wait calmly as Jordan wrangles the other boats before we make the plunge. This is just one of seven Sierra Club Inspiring Connections Outdoors trips during which Keltner’s awe study will take place.

One of the boats holds Craig Anderson, a trim, towering doctoral student who studies with Keltner. He wears a vintage Seattle Mariners cap with a GoPro camera mounted on top, which he uses to tape the kids’ interactions on the rafts before, during, and after rapids. “We can analyze people’s facial expressions muscle by muscle,” he told me earlier. “We can run the vocals through a program. Are people kidding around? Are they calm? Are they working as a team?”

Anderson and Keltner want to study the effect a two-day rafting trip will have on people’s lives, and they suspect that awe will play a major role in the story their data have to tell. Yesterday, the 25-odd students spat into vials and answered survey questions about how often they felt happy, sad, or stressed and how well they’ve been sleeping. They will spit into other vials when the trip ends and fill out similar surveys a month from now. The saliva samples will show how awe correlates with levels of stress hormones and the genes related to dopamine function.

About five miles upriver, the Chile Bar dam has closed its gates, and now what’s left of the river is literally flowing by beneath us. Jordan points to a black band on a boulder. “That rock’s already got three inches of wet. We’ll be carrying our rafts if we don’t ride this faucet.” He calls, “All forward,” and we charge toward Troublemaker.

For a few seconds, we lose ourselves. The drop sucks us into a vortex of froth. A wave plops over the starboard gunwale. And then we shoot out, bow slapping the surface, everyone gasping and soaked. A black granite fin rises up ahead. We fly around a bend into shade, and the water fades from emerald to black. Then it calms and deepens. The kids are all gasping, or smiling, or both. Jordan lets everyone in his boat jump into the water.

Jordan’s been taking his high school students on outings for over a decade. They’ve been to Hawaii and kayaked off Catalina Island, but the rivers of central California are his natural habitat. He wants to take the kids on a snow trip to see where the rivers begin, and “so they remember that there was snow in the Sierra Nevada.” I ask who of the floaters has seen snow, and half of them shoot up their hands.

Jordan stands, gets his balance, and peers downriver—a mariner in a crow’s nest. A kid bobs near the bow. The bands on the boulders are growing. “Get that road kill in the boat,” he says. “We gotta get down this river before the water runs out.”

"WHAT'S COOL ABOUT AWE is that it literally blows your mind,” Anderson says, referring to how its stimuli force people to revise their mental frames of reference. We are sitting on the bank watching night come over the canyon. Since we set up camp an hour ago, the beach has grown by 15 feet. The river is at “fish flows,” the minimum level for sustaining life.

“We might do some analyses by raft. We know emotions are contagious. If there was one really awe-prone person, did that make other people feel awe? You might have noticed that in the swimming sections, in one raft, everyone was in the water, and in another, nobody was in the water.”

For much of the night, Anderson can be found sitting on the beach, knees to chest, contemplative, eyes fixed riverward. He grew up an Eagle Scout in New Mexico. As a young child, he loved watching Star Trek and pondering the show’s moral dilemmas, and he’s still taken by the unfathomable depths of the universe. “I’ve always been into space, thinking about how vast it is. Even now, the hairs are raising on my neck just talking about it.” (Piloerection is a telltale accompaniment to awe.) His favorite awe-eliciting videos are the opening to the movie Contact and a three-minute clip that begins on Earth’s surface and gradually zooms out to one of the largest known stars in the universe, beside which our planet appears as a mere pixel. He says that he doesn’t often use segments from Planet Earth or other nature documentaries for research because viewers feel intense compassion for the animals, which muddies the results.

Before the light disappears completely, Anderson gets up to distribute paper and pens to the students, who are keeping journals as part of the study.

Today we experienced the little beauties of nature, one writes. I was able to be me and learn about the things around me.

My favorite rapid was Triple Threat. It was scary but fun at the same time, writes another.

The most amazing experience I had on this trip was meeting new people, learning new things about others, and experiencing the events with everyone. Meeting new people lets me see the different kinds of personality of each person and adds spice to life, journals a third student.

I ask Anderson if he thinks feeling awe in nature will make these kids care more about the river that’s trickling by through the dark.

“Generally speaking, yes. They say they feel more connected, not just to people but to the world around them. When you’re having your mind blown like this, people’s self-concerns really aren’t at the front of their minds. All your attention is directed outward, toward the thing that’s eliciting awe, on the outside environment, and on others around you. Also, they’re saying they’re appreciating the beauty of their surroundings, and if you’re appreciating the beauty of something, you want to take care of it. You don’t want to see it ruined.”

The next morning, we have to wait for the water. Jordan sits on a boat for hours, watching as birds putter about in the littoral zone. He sees eight species in the first 10 minutes. They pick bugs out of the mud. The dam’s daily releases determine this ecosystem’s rhythms.

Around 11:30, the river finally shows up, and Jordan calls the kids into a circle. “Let’s go, young scholars! The faucet is on!” His solemn reverence for the river is contagious. The sun peeks over the hills, bringing the temperature up by about 20 degrees.

“We’re going through a really important transition today,” Jordan says. He paces in place as he speaks, his head down as he gathers his thoughts, then he lifts his chin to project. “You’ll see that when we enter the reservoir, the biodiversity disappears. It’s like the reservoir in Oakland.”

For a while, we ride amid pale yellow, dried-out hills, with a few oak trees at the tops. “It takes a lot to live up there,” Jordan says to the kids in our boat. We pound through one rapid after another. Then he brings us into the gorge. The walls rise up and close in, and suddenly everything is greener, even the water, which intermittently bubbles and froths in emerald whirlpools. We spill into Satan’s Cesspool, bounce through Bouncing Rock. I recall a possible explanation that Keltner casually proposed for why, when people are asked to recall awe-inspiring experiences, they so often cite nature. It is Edward O. Wilson’s biophilia hypothesis: the idea that humans are instinctively fond of living systems and see life-giving power in vigorous water or dense greenery. At some evolutionary level, we think the river looks better at high flow, when the dam allows it through.

That afternoon we emerge into civilization. People are crouched on boulders, panning for gold. A family is sitting in the river on beach chairs. The water is up to their chests. It seems as if they’re waiting for the river to burst through the dam and carry them away.

We take out at a place called Salmon Falls. But there are no falls or salmon. Not anymore. The namesake hydraulics were inundated by the backup behind Folsom Dam in 1955, along with the salmon’s historic spawning route. Now they stop below the dam, where they’re corralled and turned into food. The ecosystem is all but post-natural: lifeless dirt and concrete detritus.

With his call of “young scholars,” Jordan gathers everyone into a circle for one last elegy. “Here we are at Salmon Falls. I’m glad it’s named that. We’re reminded of the salmon that used to migrate up this river into the Sierra Nevada. Now we’ve got a 100-foot dam and a 300-foot dam, and all the salmon are stuck down by Sac State, where we did the tour the other day.”

Jordan is saddened by the way the ecosystem has changed. He cares about the mergansers and red robins and the native weeds being run out by invasive weeds, the thoughtless fish swimming upriver by instinct. He would not be a good subject for an awe study. Too prone toward compassion. The T. rex skeleton would probably make him sad for the dinosaurs.

The kids each say a word to represent the hardest part of the trip and the best part of the trip. For the hardest, they say, pancakes, burning, backstroke, pans, sleeping, rocks, cuticles, revenge, current, flatwater. For the best: teamwork, carnage, stargazing, water, native, swimming, backpaddle, fun, community. Then Anderson distributes vials for the kids to spit in, and everyone returns to the city.

This article was funded by Sierra Club Outdoors.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club