Will the Circular Economy Save the Planet?

The vision of industry in harmony with nature catches on with capitalists

Illustration: Andrea Mongia

|Illustrations by Andrea Mongia

IN THE SUMMER OF 2019, William McDonough walked onto a stage at a Marriott hotel in Minneapolis wearing what he called the world's first circular pair of jeans. He was speaking at Circularity 19, North America's first major conference dedicated to "turning circular economy concepts into profitable opportunities." In the audience were Fortune 500 CEOs, investors, city managers, and government officials from around the world.

The apparel industry churns out about 5 billion pairs of jeans each year in a resource-intensive process; making a single pair requires at least 800 gallons of water and is responsible for the release of 20 kilograms of CO2 equivalents (comparable to charging your phone about 2,550 times). Add to that about a third of a cup of chemicals to achieve the colors and distressed look consumers have come to expect.

Unlike standard jeans, McDonough's duds were manufactured as sustainably as possible. The thread, care labels, pockets, and interlinings, normally made of polyester, were 100 percent organic cotton, and all the dyes, stabilizers, and finishes were made from minimally toxic chemicals. But the real breakthrough was the jeans' stretch fiber—a blend of denim and a proprietary elastane that breaks down in soil without releasing any harmful toxins and can be easily recycled. McDonough pulled the denim away from his leg and let it snap back into place. "Twenty years," the lanky, silver-haired architect told the audience with a broad smile. "That's how long it took us to get an elastane that's biocompatible." The result of a collaboration between McDonough's circular economy foundation Fashion for Good and the European fast-fashion chain C&A, the pants were already available to consumers for the reasonable price of $35.

The fashion industry is notoriously wasteful, consuming roughly 108 million metric tons of nonrenewable resources each year, from pesticides and synthetic dyes to coal and oil. Only about 1 percent of all textiles are recycled into new clothing. The majority—more than two-thirds of textiles—are either incinerated or tossed into landfills.

These problems are hardly unique to the fashion industry: Our entire economy is built on an inefficient and dangerous system of resource extraction. In 2017, the world passed a grim new annual record of 110 billion tons of resources consumed—from gravel and cement to fossil fuels, metal ores, and timber—an 8 percent increase from just two years before. According to the consultancy Circle Economy, a scant 8.6 percent of materials get reused.

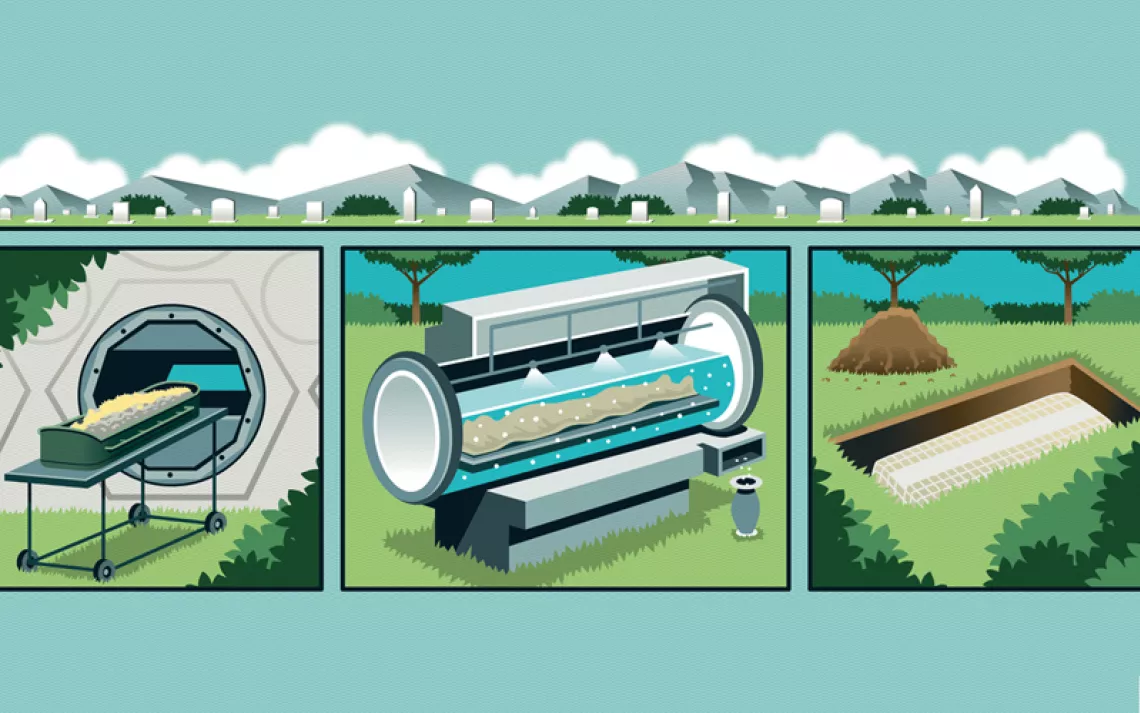

McDonough and other proponents of the circular economy aim to change all this. They promulgate a vision of industrial manufacturing that is less harmful to the environment because materials are continuously being used and reused. In their view, humanity's polluting, extractive legacy is merely a design flaw that can be engineered out by mimicking Earth's naturally circular systems.

Over the past decade, the idea of shifting the economy away from a linear model to a circular one to solve our environmental woes has taken hold in corporate boardrooms and government offices around the world. Last June, leaders from the World Economic Forum, the European Parliament, Fortune 500 companies, and environmental groups endorsed the circular economy as a way to restore the environment and promote growth in response to the coronavirus pandemic. Google, Amazon, Coca-Cola, IKEA, Unilever, and H&M have all rolled out ambitious plans to go circular. The United Nations identifies circularity as a key pillar of its Sustainable Development Goals.

While a global plan to become more sustainable sounds like progress, the circular economy is a huge and fuzzy concept, and it can be hard to pin down how exactly it translates into practice. A 2017 research paper on the topic identified at least 114 definitions of the term, with the majority amounting to little more than reuse and recycling. This is concerning because environmentalists have been championing reuse and recycling for decades, but our exploitation of resources has only intensified.

Like other utopian environmental theories before it, the circular economy promises to decouple economic growth from our endless consumption of stuff, but are its proponents really offering a planet-saving paradigm shift, or just another version of something we've tried and failed at for decades?

THE IDEA OF A MODERN SOCIETY built around nature's circular systems first emerged in economist Kenneth Boulding's 1966 essay "The Economics of the Coming Spaceship Earth." In it, Boulding described the urgent need to transition away from an "open economy" of careless resource extraction, production, and consumption to a "closed Earth"—a cyclical economic system that preserves and maintains resources by creating products that never wear out.

In the 1970s, Swiss architect Walter Stahel further advanced the concept of a looping economy in an influential report for the European Commission in which he imagined jobs created around large-scale reuse and remanufacturing of durable consumer goods. Companies would lease everything from tires to lighting to vehicles and recover them for refurbishment and recycling. In the 1990s, industrial ecology, now a widely practiced field of environmental science, was promoted by sustainable strategist Hardin Tibbs, who proposed that economies be built around a "continuous cyclic flow of materials," with the outputs of one industrial system used as inputs for another.

It was McDonough (often called the father of the circular economy) and German chemist Michael Braungart who pushed the concept from academic exercise into mainstream discourse. Many environmentalists, myself included, were introduced to the heady ideas of circularity through their visionary 2002 book, Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way We Make Things, which paints a picture of consumer products—from shoes to sedans—that could regenerate ecosystems rather than harm them. "If humans are truly going to prosper," the two wrote, "we will have to learn to imitate nature's highly effective cradle-to-cradle system of nutrient flow and metabolism, in which the very concept of waste does not exist."

Through their environmental consulting firm, MBDC, and their Cradle to Cradle Certified program, McDonough and Braungart have sought to bring their ideas to life. One of my favorite projects was an early concept car for Ford called the Model U, whose parts were designed to be easily disassembled and repurposed. The car top was compostable, the interior was made from recyclable polyester, and the engine was a made-to-last hydrogen fuel cell. Some of McDonough and Braungart's other innovations, including recyclable chairs by Herman Miller and carpet tiles for one of the world's largest flooring companies, are in production today.

The various proponents of the circular economy are inspired by nature's capacity to eliminate waste by transforming it into new fodder for ecosystems (Cradle to Cradle uses the example of a cherry tree's falling blossoms feeding the soil). But a practical guiding principle runs through their theories. "What all of these fields of study and contributions are saying is that resources are finite," says Jennifer Russell, an assistant professor at Virginia Tech and a leading circular economy scientist. "We need to be careful about where we're getting them, how we're using them, and what we're doing with them when we're done with them." It's a straightforward idea, but whether its practical application can make a dent in our resource consumption has yet to be fully tested.

In FALL 2020, H&M, the fashion brand perhaps most infamous for producing high volumes of disposable clothing, debuted the world's first in-store garment-to-garment recycling machine at its flagship location in Stockholm. Shoppers can book a time to watch as a set of eight machines sanitize an old T-shirt, chop it up, then spin and knit it into a brand-new sweater, baby blanket, or scarf. The process takes around five hours but costs at most $16, about the same rock-bottom price as a new H&M sweater.

Responding to decades of pressure from activists and consumers, the fashion industry has seemingly made the most progress applying circular economy principles. Around the same time that H&M unveiled its textile-recycling machine, ASOS, a British fast-fashion company, launched its Circular Collection, featuring reversible T-shirts and unisex suits that are durable enough to be passed between multiple owners on the secondhand market, jeans made from 100 percent cotton so they're easy to recycle, and a zero-waste peasant blouse (no scrap of fabric goes to landfill in its design process). The American shoe company Timberland has launched a line of its iconic yellow boots that are easy to disassemble; 80 percent of the materials can be recycled.

Perhaps more significant (if less technologically alluring), a number of apparel companies are developing business models that revolve around extending the life of the clothes they produce. The secondhand-clothing sector is growing 25 times faster than fast fashion, according to a report by ThredUp, the world's largest online thrift store. Eco-minded brands like Patagonia and Eileen Fisher now refurbish and resell their own secondhand clothing. And consumers are responding to the trend. The RealReal, an online consignment store for designer clothes, became the first unicorn (valued at $1 billion) circular business in 2019.

But the real cutting edge for circular fashion is material innovations that enable fiber and footwear components to be reused over and over again without degrading, keeping materials out of landfills and potentially zeroing out the need for virgin fibers. (Current recycling technology produces lower-quality materials that are usually blended with virgin materials.) We're closer to this science-fiction-sounding scenario than most people realize. Seattle-based start-up Evrnu's NuCycl fiber, for example, is made by turning used cotton into a pulp and drying it into paperlike sheets that can then be dissolved and spun into new fibers. NuCycl yarns can be recycled multiple times with no loss in quality, according to Evrnu founder Stacy Flynn. Clothes made from NuCycl should debut in Stella McCartney, Levi's, and Target stores in 2021. Likewise, H&M is making some of its pieces from Renewcell, a nearly identical technology. These innovations amount to a fraction of the overall output of the apparel industry, but they offer a tantalizing vision of what circular design could look like across the sector. "You've got active reuse systems, you've got active repair systems, and you've got refurbishment that's happening," Russell says. "Fashion is really stepping up and trying to own this space."

Companies outside the fashion industry have also introduced circular economy initiatives in recent years. IKEA has committed to making all of its furniture out of renewable or recyclable content by 2030. The company is rolling out its Second Life for Furniture program, which pays customers for their gently used IKEA furniture and resells it in stores across 27 countries. Coca-Cola, 3M, Procter & Gamble, and Unilever are pouring millions of dollars into recycling infrastructure to "close the loop" on plastic pollution, and Apple is launching a 9,000-square-foot facility in Austin, Texas, to refurbish more of its phones and gadgets.

IT'S HARD NOT TO BE DAZZLED by circular innovations like an in-store recycling machine that spits out a new sweater. But as the circular economy scales up, and case studies emerge in real life, problems with the concept are coming to light.

Circularity promises an exciting world of technological progress where we can have it all—the trendiest jean silhouette, the latest gadgets, single-use plastics—without harming the planet. Some of the world's largest disposable-goods companies are advertising their commitment to circularity as a win-win for consumers and the environment. Levi's SecondHand tagline reads, "If everybody bought one used item this year, instead of buying new, it would save 449 million pounds of waste." And H&M says, "If we use a recycled cotton shirt to make a new shirt, there's no need to grow more cotton." The suggestion is that as long as we reuse and recycle everything, we've "closed" nature's loops and avoided ecological damage. The reality is far more complicated.

To begin with, it's important to note that the business community is promoting circular economy projects involving resale, rental, and even more-durable design to entrepreneurs as an additional revenue stream. A 2016 McKinsey & Company report on circularity frames it as an opportunity to expand markets to a new customer group without cannibalizing existing sales. It estimates that the European economy could unlock about $2 trillion from new circular economy businesses like electronics refurbishment and textile-to-textile recycling and simply from the "increased spending fueled by lower prices" associated with shared and secondhand products. Likewise, the business consulting firm Accenture promises a staggering $4.5 trillion windfall from investing in new circular economy businesses, including those that focus on advanced recycling technology, innovative new recyclable materials, sharing platforms (like ride or home sharing), or subscription models (like fashion-rental website Rent the Runway). Russell concedes that most big businesses that are exploring circularity aren't doing so at the expense of their main revenue streams. "These companies are not abandoning their make-new-products strategy," she says.

What that means is that in fashion and elsewhere, the circular economy is not replacing the linear economy; it's merely running parallel to it. In other words, circularity is being positioned as a way to drive new growth, not necessarily as a way to cut down on the use of raw materials. There's no evidence that any of the large brands embracing circularity are actually using fewer virgin resources overall. The fashion industry is a case in point: It still manufactures an estimated 100 billion garments annually, enough for every human on the planet to buy something new to wear every month. Total production of virgin textiles—whether polyester, cotton, or rayon—hit historic highs in 2019.

What's more, by emphasizing reuse and recycling—rather than reducing production—the circular economy runs the risk of becoming a red herring, enabling companies to increase their environmental impact while appearing greener to the public. The circular economy is essentially riding on decades of public conditioning that has us convinced that reuse and recycling are always good for the planet, but that's not the case. "We've tried [reuse and recycling] over and over again, and it just hasn't worked," says Roland Geyer, a professor in industrial ecology and pollution prevention at the University of California at Santa Barbara and a critic of the circular economy.

The economics and difficulty of recycling complex consumer goods like electronics, cars, and furniture mean that wide-scale refurbishment and recycling of most products remain elusive. But even if industry were to overcome these barriers and finally scale up recycling, virgin-resource consumption still might not decrease. This is partly because recycling itself requires water, energy, and chemicals. It is far from a zero-impact process. In the case of recycling textiles, energy is needed to spin old fibers into new material, then chemicals are required to dye and finish that material into garments, and more energy is needed to ship them to retail stores. A 2018 Quantis report on the fashion industry found that scaling up to clothing made from 34 percent recycled materials would only cut carbon emissions across the industry by a mere 5 percent.

In fact, designing products so they're made to be recycled and reused could drive up overall consumption of virgin resources. In a 2017 paper, Geyer and environmental science and management expert Trevor Zink explain how the circular economy could be initiating a rebound effect. Besides creating new and separate markets for cheap secondhand products that don't replace new products, it could dramatically increase the supply of recycled materials. This would put them in competition with virgin materials, driving the price of both down and the consumption of both up.

Steel, for example, is the most widely recycled material, and yet consumption of primary steel has doubled in the past 20 years. Because the total consumption of resources is growing by about 3 percent every year, it's difficult to make every new thing out of old things, which means recycled material will always be in competition with virgin material. "The whole point, the only point, of reusing and recycling is so we make less new stuff," says Geyer. "And that's just not happening."

Despite decades of enthusiasm about the circular economy, today's world is much further away from being sustainable than when Cradle to Cradle was written. The Model U still hasn't been mass-produced, the amount of carpet landfilled in the United States has nearly doubled, and more than 9 million tons of furniture winds up in the trash in the United States every year. Electronics are now the fastest-growing waste stream in the world.

RUSSELL KNOWS ALL THE potential downsides of the circular economy. She agrees that recycling is "the last thing we want to focus on" and that the whole endeavor could fall prey to greenwashing. Still, Russell maintains that reuse and refurbishment scaled up across society could result in environmental gains, as long as we can figure out how to tame the rebound effects and hold down primary consumption—though she concedes that these are big ifs. "It makes a lot of sense in theory, but the problem is figuring out how to get from where we are now to where we want to be," she says.

Russell also believes that growth remains inevitable under our current economic paradigm. "Unfortunately, companies still have to satisfy shareholders," she says. Until we change that, new businesses are going to start every year, and the circular economy is the better alternative because it's ensuring that new growth comes from lower-impact activities, like refurbishment, resale, and recycling. "People still need to be employed," she says.

So no, the circular economy isn't going to save the world. But according to Russell, it's still a useful framework for pushing for change. She sees it as the training wheels to help our consumption-addicted society begin to move away from its linear ways, a set of principles that could, over time, nudge businesses, shoppers, and even governments toward the responsible use of resources. "It's the thing that's going to help us get through the next few decades—I hope sooner—to change behaviors and make us realize that we have a problem and that we also have the ability to do something about it."

Like Russell, Geyer believes that a circular economy, even one grounded in reuse and recycling, could help us get closer to our ultimate goal, which is to live within the planet's boundaries. But that won't magically happen. Nations and companies will have to commit to constraining virgin-resource usage. "If we're serious about environmental sustainability, we cannot afford for virgin-material production to grow at all, quite frankly," Geyer says.

There are some signs that regulatory bodies are starting to recognize this. The European Union has set requirements for consumer products to be repairable, upgradable, and durable, and the Netherlands, considered a leader in circularity, has set a goal to half its raw-material consumption within a decade. But as of yet, no country has decoupled resource consumption from growth, nor have any consumer-goods companies. So far, the environmental benefits of the circular economy exist mostly on paper.

I RECENTLY READ CRADLE TO CRADLE again, tumbling into its visionary world of industry in harmony with nature. Nearly a hundred pages in, it hit me that McDonough and Braungart's vision doesn't have all that much in common with the circular economy paradigm that's emerged in recent years.

The most impactful aspect of the cradle-to-cradle system is redesigning products and industries from the start to be nontoxic and regenerative, using as much renewable energy as possible along with safe chemicals and materials. Remaking new products from old ones and keeping them out of the landfill is only the final step in a completely transformed industrial process. What's truly circular about McDonough's jeans, it occurred to me, is the fact that they were produced in a way that minimizes harm and they can be safely composted in my backyard. The least impressive thing about them is that they're recyclable, which essentially renders them as feedstock for a wasteful industrial system.

I called McDonough last September to ask him what he thought of the movement that he'd helped spawn. He didn't hesitate to voice his trepidation.

All too often, McDonough said, the circular economy is boiled down to chasing higher and higher rates of recycling without paying enough attention to the types of materials being circulated (like plastics that shed microfibers and come from fossil fuels or textiles that contain hazardous chemicals). "It's all about quantity," he says, whereas Cradle to Cradle is about quality. What does he think about reorganizing the entire business sector around reuse and recycling? "If it's seen as the panacea," he says, "then I think that can be problematic."

And yet, Cradle to Cradle is fiercely pro-growth. McDonough and Braungart argued that all business and industrial growth is natural, that economies, just like organisms, die without it. Producing a lot of stuff is fine as long as that stuff behaves like the blossoms of the cherry tree, falling to the soil and returning to nature. This stance seems naive now, given the explosive rise in disposable consumption since the book was published. Fast fashion barely existed two decades ago.

The notion that we can go on making as much as we want as long as we reuse it all is a myth that we'll have to leave behind if we ever want to realize the dream of a circular economy. "We're already past the carrying capacity of the planet," Russell warns. "Unless we repair something without also buying something new—unless we buy a used coat and don't also buy a new one—we are still perpetuating the same system. We'll just have two different marketplaces, and we'll be buying from both."

This article appeared in the January/February edition with the headline "Will the Circular Economy Save the Planet?"

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club