Sierra Club Napa Group

White Paper on Water Sustainability Management

Summary

Far from exhaustive, this list of necessary actions is essential to beginning a path to a sustainable water management system within Napa County. Decisive leadership is required to address the crisis we are heading toward. Basic actions that need to be taken by the Board of Supervisors include:

1. Growth limits

The county cannot permit new and expanded water use when the supply is undergoing a long-term decline. That’s not policy or ideology, it’s arithmetic. Do not permit any development that increases total water use at all. Any permitted project must be a net zero water consumer.

2. Implement LAFCO recommendation to consolidate water districts

The Local Agency Formation Commission (LAFCO) commissioned a study on the county’s water and wastewater systems. The analysis revealed significant inefficiencies and inequities between the many agencies within the county that would be improved by consolidating agencies into a single county agency. Consolidation would enable substandard systems to be upgraded and a shared management of a shared system.

3. Watershed-wide sustainability management

Within a watershed, defined by the topology of an area, all water is one. It falls as precipitation, becomes surface water and groundwater, sometimes moving back and forth. It flows down hillsides to the valley floor, and ends in the sub-basin or flows out to the ocean. It’s a system. Manage it as a system, rather than limit discussion and planning to just one aspect.

4. Monitor and measure effectively

One cannot manage water sustainability without knowing inputs and outputs. Estimations and honor system reporting inject uncertainty, biases, and variability into a process that then creates forecasts and models. We need actual data. Wells should be metered. Well levels should be monitored. No grandfathering. Base analyses and decisions on facts.

5. Withdrawal permitting

It is essential that if we monitor extraction and diversion of water, we should actively manage extraction and diversion with permitting. A host of beneficial functions can be incorporated into a permitting system that would protect small farms and domestic wells, allow for equity provisions, and make management active rather than passive and reactive.

6. Limit trucked water use

Trucked water is the transfer from one source, often urban, to agricultural. Businesses should not be allowed to rely on trucked potable water for operation. Business expansion that includes trucked water should not be approved. Permitting of trucked water should require plans for sustainability without trucking in water.

7. Actual community participation

The process has been managed to have limited representation by various community and environmental interests (but not minority or disadvantaged communities). It has been actively managed to have controlling representation of the large water users who have interest in maintaining the status quo. The controlling interest have interest in development, expansion, and minimal accountability on the part of the largest water users. This needs to change, or the status quo of unsustainability will be sustained. This issue has been addressed in depth in a recent open letter from Save Napa Valley.

Purpose

The Sierra Club Napa Group has followed and attempted to participate in the county’s sustainability planning and management effort. To date, we have seen significant opportunities missed and a high level of activity grossly insufficient to assure the sustainability of our water systems, particularly in light of climate change. We have witnessed significant consultant expenditures and voluminous reports that overwhelm the ability of citizen committees to process, while missing the key decisions that are essential to any path toward sustainability.

In this document, we list a few essential actions that must be taken by our elected officials. Without these actions, sustainability will be out of reach, and the likelihood of emergencies will increase.

Perspective

Much attention has been focused on water sustainability in the Napa sub-basin. The sub-basin is just one part of a system; we, the Sierra Club, are focused on the whole system of the Napa River watershed as well as water sustainability for the county as a whole. Creating studies, management, and solutions for one part of a system inevitably leads to sub-optimization and false successes. We seek to avoid paper successes in favor of creating a management process for the whole system involving all communities.

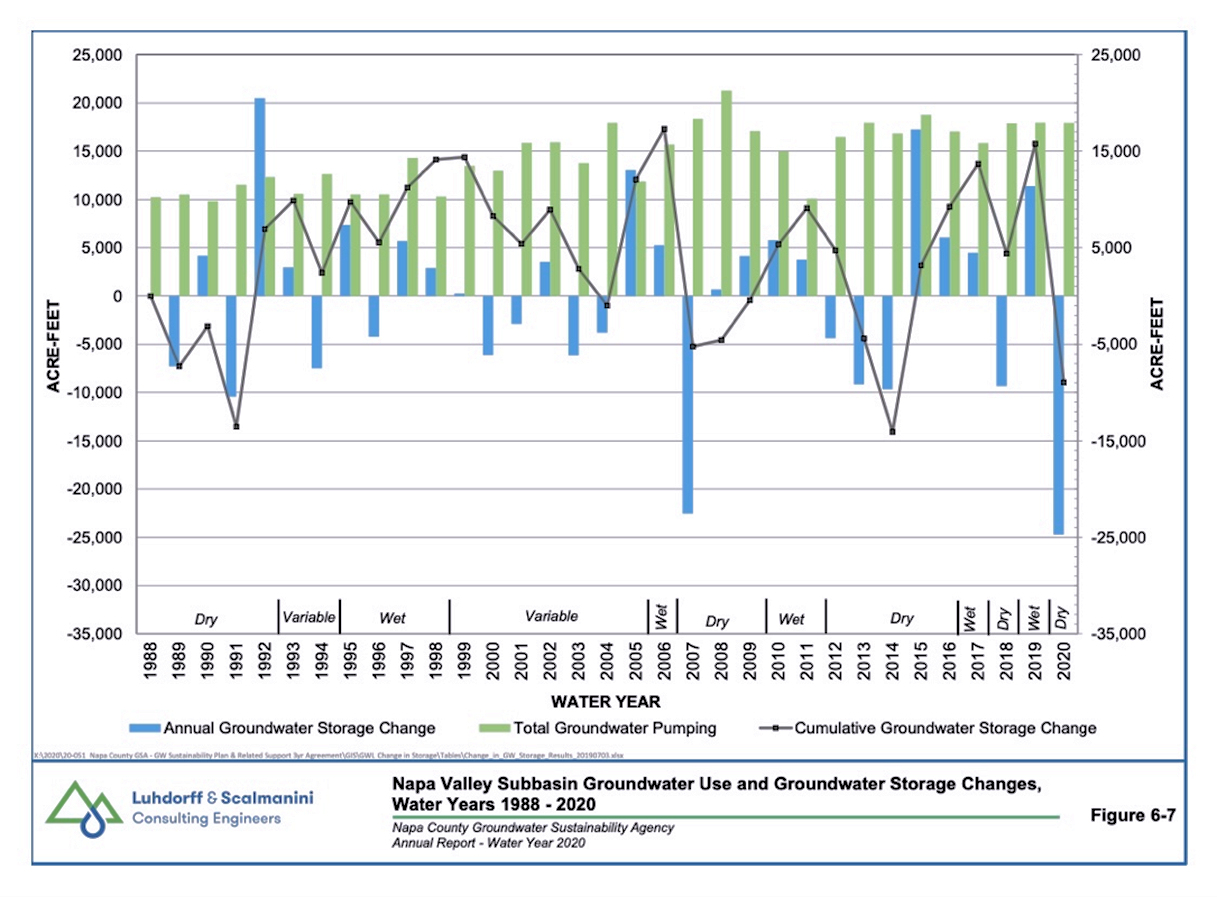

The first given, the factual condition we are in, is that the Napa River sub-basin, the low point of the valley water system, is in overdraft. Year after year, more water is pumped from it than is replenished. This fact was buried in a complex graphic in an appendix to a report to the county from its consultant. It was surfaced by a tireless Sierra Club reviewer. It was inserted into the GSPAC discussion after the Sierra Club published it in comments on deficiencies in the draft GSP. This might not have been included in the GSA action plans were it not for this citizen diligence.

From the Sierra Club Napa Group response to the GSP:

The situation in the Napa Valley Sub-basin is especially critical and in need of Project and Management Actions to reduce groundwater pumping and to curtail development that will entitle new pumping. According to the GSP, the Sub-basin sustainable yield, as defined by SGMA, is approximately 15,000 acre-feet per year (GSP Executive Summary).

Groundwater pumping has exceeded this amount since the water year 2012, as shown by the Total Groundwater Pumping bars in Figure 6-7 (pg 199) in the 2020 Napa Annual Groundwater Report.

The natural unit of study and management of water resource is the watershed. A watershed is a natural topological feature that receives precipitation and brings it down along hillsides into groundwater and surface water flows, and into the lowest points, sub-basins, and then rivers that flow out of the watershed toward the ocean. Water flows downhill. Focusing sustainability management on the lowest elevations creates a mindset that is reactive and driven by the detection of failures. The water flows within the watershed are very interdependent; the health and sustainability of one part of the watershed is joined to the health and sustainability of all the others.

We cannot rely on imported water

Water may be imported into an area from areas of surplus, and exported, either as surplus water or in the form of products, whether agricultural products or as commercially bottled as branded water.

The import of water from outside sources can fulfill water demand that exceeds the sustainable amount available in the watershed, but it also makes the local supply vulnerable to the sustainability of other areas. Availability of imported water is also dependent on demands from other communities within the state. Dependence on imported water should be considered a vulnerability, particularly in an era of climate change and increasing demand. We cannot reliably budget for imported water; we can see that allocations from the State Water Project cannot be relied upon. Emergency allocations from sources such as Berryessa cannot be planned for; it stresses the sustainability of that water source which is also subject to increasing demand because of regional drought. We strongly advocate for sustainability management to focus on long term sustainability without the reliance on imported water.

Sustainability for the watershed and for the count

Political entities, whether city, county, or district do not neatly map onto the natural units of water management - watersheds; jurisdictions may contain portions of watersheds or multiple watersheds. Our considerations and policy recommendations are for sustainable watershed management as well as sustainable and equitable distribution of water resources within the political entity, the county.

We offer a summary of our research, as a service to elected officials and candidates for office who have a role in developing and approving regulations and permits.

Key positions

We have shared our analysis of methodological weaknesses of the process that created the GSP. There are a few action items that are in the sphere of influence of county elected officials and their staffs. We would like to see advocacy and action on these items.

1. Growth limitations: Net zero water usage requirement

We find that water resource in Napa County is a zero-sum game. Greater use by one community comes at the expense of the others. Growth plans, whether in increased residential population, hospitality businesses, or land under cultivation, all assume availability of water. Each bit of growth increases water usage while total available water is in decline due to climate change. This is the definition of unsustainable.

We can support development and growth only when long term availability of water can be ascertained, and new water extractions are offset by mitigations, such as recycling and conservation. This is a “net zero” approach to growth. American Canyon has implemented such a requirement; we believe it is necessary for the whole county. We might envision a usage credit marketplace where real savings may be transferred from one business to another as a way to facilitate creative solutions and an incentive to conserve.

We suggest that development permits be conditional on net zero fresh water usage and that if a permitted development violates these conditions, the permit is suspended. That means that a business will not be able to extract water or operate as a business until it comes into compliance with its permit. Violators should not be allowed to submit for variances or modifications of permits.

2. LAFCO implementation: County-wide water and wastewater agency

LAFCO commissioned a study by Policy Consulting Associates, LL.C. and Berkson Associates on water agencies in Napa County. In the public review draft, dated May 18, 2020, the report noted the inequities in access to water, disparities in facilities and a Balkanized collection of agencies within the county that amounted to variability in compliance with standards, reliable access to fresh water, and areas in need of common regulation, such as trucked water. They strongly recommended that Napa create a single unified agency for the whole county, incorporating the large, small, and unserved communities into one agency. LAFCO incorporated that into their recommendation to the county, which has not been accepted. We strongly support a county-wide agency.

From the Consultant Report:

GOVERNANCE STRUCTURE ALTERNATIVES

Over the course of this MSR several governance options were identified with respect to each of the agencies under review. These options are summarized in the Overview chapter (Chapter 3. Refer to the affected agency’s chapter for discussion on options specific to that agency.

In addition to the agency specific options, the potential for a county water agency and/or a countywide county water district was also identified. These options have the potential to affect many or all of the reviewed agencies and have far reaching impacts on water and wastewater services in the County. Benefits to forming a county water agency or county water district include:

- Efficient use of the County’s water resources,

- Enhanced water resource management,

- Solidarity amongst Napa water purveyors with greater leveraging power,

- Greater scrutiny of all utility providers,

- Enhanced technical and operational support for local providers,

- Elimination of redundancies and duplication of efforts amongst the smaller systems, and

- Improved economies of scale.

It is recommended that water purveyors in Napa begin discussions regarding their vision for water utilities in the County in the long term to address existing concerns and ensure a persistent and stalwart effort at providing reliable and sustainable water services throughout the County.

3. Watershed-wide sustainability management

As described in the introduction, the natural unit for water management is the watershed, the area defined by a ridgeline, with water migrating toward the lower elevation features of rivers and basin. While Napa County contains all or part of several watersheds, the largest and most significant is the Napa River watershed.

The State Department of Water Resources (DWR), in compliance with its role in administering the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act, designated the Napa River subbasin as a “priority 1” basin, meaning that there is significant and increasing demand on groundwater, and that the basin needs a plan and an agency to actively manage water resources to avoid overextraction and other adverse impacts.

This designation triggered a mandate to create a Groundwater Sustainability Agency (GSA) and Plan (GSP) to be submitted to the DWR for approval and oversight. The county vigorously opposed the creation of a GSA and the development of a plan, asserting that there was perfectly adequate sustainability management without the additional oversight. That adequate management was the one that overlooked the over-drafted state of the sub-basin groundwater.

Why the focus on the sub-basin?

The GSP focus on the sub-basin as the water resource to be managed is not because it is somehow separate from surface water or water in aquifers outside the designated sub-basin. It is not because this is the singularly most critical water resource that needs to be managed. It is because water law separates groundwater and surface water into two bodies of law, precedent, and regulatory authority. The DWR has authority over groundwater, not surface water, so its ability to mandate practices is correspondingly constrained. The DWR and SGMA also do not and cannot proscribe good sustainability practices in surface water or in integrated water management.

A common groundwater feature within a watershed is the sub-basin, the area under the lowest part of the watershed, and a significant storage structure for groundwater. It is well defined because the United States Geological Survey has consistently and precisely mapped sub-basins for watersheds. As such, it is a common feature in all managed areas that is consistently and precisely defined.

Neither of these is reason for county oversight to focus only on the sub-basin or subordinate the study and management of all water systems in a watershed. The condition of the sub-basin is very dependent upon the condition and management practices in all the other parts of the system, whether surface or groundwater, whether hillside or basin.

Many have been led to believe that the GSA is proscribed from managing the sustainability of the whole watershed. That is simply not true; the DWR doesn’t have the power to mandate a comprehensive view. It likewise does not have the power to prevent considerations of all aspects of water by one local agency. Suppression of discussion of the whole system does not serve the needs of any community; it only serves to achieve a recorded state of compliance with regulations. Suppression of discussion of the whole water system suppresses inquiry, discussion, discovery, and action that will prevent adverse conditions.

As it happens, when it came time for the Board of Supervisors to designate the membership of the GSA, they designated themselves, a political body, as the GSA. As the Board of Supervisors, they actually have more power than is invested in GSAs that are not also the most senior political body in a county. The Napa BOS/GSA does have the power to develop plans for sustainability that are integrated and rigorous, and not be overly constrained by authority stovepipes.

We very strongly advocate the creation of a water sustainability plan that manages all water in the valley, not just that that is flowing under the ground in the bottom of the valley.

The BOS/GSA has the authority, and it has the duty to look at an integrated view of water in Napa[1]. The county may not have the authority to change surface water rights, but can monitor and engage the state agency in setting limits. Failure to do so can result in compliance with just one legal mandate along with a potentially catastrophic failure serve all communities in the county. Isolating and serving only one aspect of water is a breach of public trust.

4. Monitoring and measuring

You cannot manage what you do not measure. We cannot know the true condition of water resources without rigorous monitoring and measurement programs. A good measurement program will give early warning of trends toward unsustainability and point toward causes. This will enable action before there are crises. Those programs need to be instituted as soon as possible, and not when we find ourselves in a declared emergency.

We need to measure:

- The level of all wells in all locations. The frequency of measurement should capture seasonality, as well as the impact of water diversions in the same area.

- Metering of wells in all areas, with the exception of domestic wells. Grandfathering of well permits should be brought up to date and all wells should be required to be metered, with only the domestic exception. Ideally, telemetry can enhance the collection of data into automatically created reports.

- Streamflow monitoring should be of the level of the water from the bottom of the stream, and also volume, dissolved oxygen, and other indicators that biological experts have determined important for sustainability of fish and riparian vegetation.

- The frequency of streamflow measurement should be relevant to the success of species, particularly migrating and spawning species.

- Surface water diversions should be metered just as well water is.

Data from these measures should be easily queried and reported by any member of the public.

5. Groundwater Extraction Regulations: Withdrawal permitting

The GSP recognizes a need for a Groundwater Pumping Reduction Plan (GSP Management Action #2, targeted for workplan development in 2022). This aims to address the current situation in which groundwater extraction has exceeded the sustainable yield of 15,000 acre-feet/year for the seven-year running average (2016-2021).

The GSP discusses an overall reduction strategy in which reductions would be applied to all wells with the sub-basin that are not de minimis groundwater users and suggests a reduction that retains approximately 75% of groundwater pumping to achieve a savings of 1500-5000 AFY.

“A modeling scenario was developed to simulate the potential effects and benefits of reduced groundwater pumping. The scenario focused on agricultural and landscape irrigation. Using simulated monthly pumping in Scenario A, a threshold value of approximately 75 percent of total monthly groundwater was implemented (Appendix 8A). The resulting reduction in simulated pumping ranged from 1,500 and 5,000 AFY with respect to Scenario A.”

(from https://www.countyofnapa.org/DocumentCenter/View/22909/GSP_Section-11_Sustainable-Groundwater-Management-Projects-and-Management-Actions?bidId=, page 11-34)

However, a pumping reduction plan is a reactive measure. A more wholistic approach to groundwater management should include groundwater withdrawal permitting for all groundwater users (as required in Arizona, New Mexico, Nevada, Texas, and Utah). The Stanford Water in the West program provides information on the benefits of groundwater permitting:

a) Withdrawal permitting can reflect local, regional, or state priorities and preferences.

Withdrawal permitting can take legal form in state statutes or in ordinances by local agencies that are granted permitting powers by the state. There are examples of local, state, and hybrid approaches to management. Because permitting regimes are developed through legislation and regulation, the principles reflect the preferences of elected representatives and can be amended if public perspectives change.

b) Permitting regimes can consider equity, efficiency, or socially preferred water uses.

Permits to withdraw groundwater are conditioned on a variety of factors, including the amount of water pumped and the use of the water. Most areas exempt certain types of withdrawals (i.e., domestic or stock watering) from permitting requirements

c) Withdrawal permitting can broaden the concept of sustainability beyond “safe yield”.

Historically the law limited total groundwater extraction to “safe yield,” but permits allow for the consideration of a range of issues affected by groundwater pumping, including impacts on other water users, environmental effects, future water needs, and the public interest.

d) Permitting regimes and “good” science go hand-in-hand.

Informational tools like metering and monitoring are often mandated by permits criteria to collect data about groundwater levels and use. Fact and data-based monitoring and decisions will lead to progressively better decisions and planning.

e) Permitting regimes provide the foundation for water markets.

Groundwater permits often specify a precise amount of water allocated to each user and require monitoring of actual pumping levels. These two factors can form the basis for trading of groundwater rights or allocations.

Groundwater permitting for agriculture could ensure that water is actually needed and is being used in the most efficient way possible by restricting use in areas that can be dry-farmed and by requiring irrigation assessments for vineyards (currently offered by the Napa County Resource Conservation District and required as a part of the Napa Green Vineyard Certification). Permitting for commercial uses could require recycling water in-house to minimize extraction.

6. Trucked water: limits on commercial use

When domestic wells go dry, often because of adjacent over-pumping, homeowners are forced to have water trucked in. For the homeowner, it is a survival necessity.

Winery, hospitality, and vineyard operations are using trucked water as part of their planned operations. We don’t know the volume of trucked water because records are not available. These businesses don’t have sufficient local water to operate at the scale they wish. These operations are, by definition, unsustainable. Trucked water becomes the workaround to groundwater limits.

The water that is trucked in is typically taken from municipal sources, effectively transferring an urban resource to agricultural use.

Trucked potable water should not be allowed for the on-going operation of commercial enterprises. If those businesses cannot operate with the water supply they have, they need to find the additional supply via use of recycled water, conservation, or scaling back their operation to sustainable levels.

Trucked water for domestic use when wells go dry should be allowed.

Delivery of trucked water should be recorded and reported. A business that uses trucked water during a year should be required to file a plan to become water sustainable in subsequent years, not allowed to grow in water requirements, and be subject to fines or sanctions for continuous use of trucked water.

The water that is trucked is not created out of thin air; it draws on resources designated for other communities. As such, it should be constrained. Sustainability plans and practices should be required of all businesses.

7. Active involvement of all communities

The process of developing a groundwater sustainability plan has been dominated by the wine industry. A few environmental representatives participate in the proceedings, but have largely been marginalized.

The draft plan has largely been developed by a consultant hired by the county, and then moved through the process with only marginal modifications by the GSPAC. Participation by communities consisted of only three presentations at the end of the process, and citizen input carried no weight. Minority and underprivileged communities had no voice at all, either in the development process nor in the after-the-fact presentations.

Attempts to bring new ideas or challenges into the process were subject to real time rebuttals without opportunity to discuss or debate.

We need full participation on the front end of plans and equitable treatment of all communities, particularly those that have less political influence in decisions.

a) Residential

Consideration of residents is key, and that applies to residents in cities, towns, and in remote areas that are dependent on groundwater. The voices of those who see wells go dry when nearby businesses pump more water should be listened to.

Low-income well-owners: A special category of domestic well users is low income well users. When their wells go dry, they do not have the means to find new groundwater or afford the expense of trucked water.

The County is under mandate from the state to develop more housing for an increasing population. Long term water availability should be considered in permitting such developments.

b) Business

The business community is well-represented in water planning. We might say over-represented, as they occupy more seats in decision-making bodies, and participants nominally representing government agencies are acting in the service of the elected officials who appoint and direct their activities. The agri-business interests should accept that they are part of the problem in order to be part of the solution. They should voluntarily initiate measurement and information sharing and acknowledge the legal status of water resource as a shared asset and not an entitlement.

c) Ecosystems

The most voiceless community consists of ecosystems. They are an interconnected web of mutual dependencies that collectively depend on reliable water resource. When public officials develop grand water budgets, they typically do so on “water year” bases – annual budgets. The anadromous fish, however, don’t benefit from such gross units of management; they need a flow of cold water to swim upstream to spawn at specific times of the year.

We can parse ecosystems into components so that we can organize measurement and management activities, but we need to be mindful that the minimum unit of water monitoring and management is a whole watershed. It is interdependent in ways that we learn of only when we cause it to fail.

The SGMA reporting requires us to monitor groundwater dependent ecosystems (GDEs), focusing our attention on the area it has jurisdiction over, the groundwater. Watershed woodlands are part of GDEs, too. Mature woodlands and forests contribute to percolation of rainwater into aquifers rather than erosively run off.

The bigger picture

In the 2022 California Water Law Symposium, indigenous presenters who were expert in water law and treaty history, described the fundamental difference between indigenous and Euro-centric views of natural resource management. In American approaches, things are divided up and treated separately. Small scope problems with many small scope solutions that typically conflict with each other. Private property rights make all solutions contentious because often the gain for the community is experienced as a loss to a property right holder.

In the indigenous perspective, if the river is not well, the fish will not be well. They are one thing. The people need sustainability of the fish to be healthy, so the health of the fish stock is linked to the health of the people. The water, the fish, and the people are really one. The health of each is linked to the health of all. Water, fish, and people and not treated as resources to be exploited. They are appreciated as parts of the same body. Nobody has greater rights than the needs of the whole community.

As we consider sustainability of water for our many interdependent communities, we have to realize that many communities have been given privileged rights and will relinquish those only under duress. We create jurisdictions and regulations that parse nature up in ways that nature will refuse to respect. If we are to find a shared path to a future that includes a changing climate, we need to consider the system as a whole, as nature provides, and to address needs with full consideration of all communities, privileged, underprivileged, and nature itself.

[1] https://lawreview.law.ucdavis.edu/issues/45/3/Topic/45-3_Frank.pdf