Drops of Hope Along the Colorado River

After 174 years, the Navajo Nation is still trying to regain access

Update: On June 22, the Supreme Court ruled 5-4 against the Navajo Nation, striking down the Navajo claims that the federal government has an obligation to help the Navajo access Colorado River water rights.

“It snowed again!” exclaimed Crystal Tulley-Cordova during a phone call on a frigid January morning. After years of drought, it felt like a relief. “This is the most snow the Navajo Nation has seen in a long time,” she said. Only months before—in summer 2022—the nation had been in severe drought. Now it was facing a different emergency, as a lack of local tribal resources to clear roads of snow had left many people without access to food, medical services, and water.

Tulley-Cordova, 40, grew up in the remote community of Tohlakai, New Mexico. She and her family were “water haulers”: They had to drive to fill a tank on a trailer at a “watering point,” which was a livestock well. “I didn’t grow up thinking that water comes out of the tap,” she said. “When you are a water hauler, you have an understanding that the water is coming from somewhere. The water that I grew up on was essentially unregulated livestock water.”

Navajo Nation hydrologist Crystal Tulley-Cordova: “I didn’t grow up thinking that water comes out of the tap.”

Like Tulley-Cordova’s family, up to 40 percent of families in the Navajo Nation lack piped water. And like their watering point, many other tribal water sources are feared to be polluted by salinity (from drought and oil production) and the toxic legacy of uranium mining. Even so, Tulley-Cordova’s grandmothers taught her a lesson that would shape her life: that water is connected to the land it comes from and that every drop is unique.

Tulley-Cordova went on to study climate change and its effects on hydrology at the University of Utah. Her PhD dissertation focused on the science behind her grandmothers’ traditional wisdom: pinpointing the stable isotopes that give every drop of water a signature, a thumbprint of its origin, be it from snow, rain, lakes, streams, springs, or groundwater. Now, as one of the Navajo Nation’s principal hydrologists, Tulley-Cordova is responsible for the water security of 173,000 Diné (as the Navajo call themselves) as they struggle to adapt to a 23-year drought, the Southwest’s worst in more than 1,000 years. The significant snowfall last winter provided only a glimmer of relief. “Drought and above-average precipitation and flooding concurrently exist,” she said. “People don’t realize this. It would take a decade-long string of above-average winter precipitation to reverse this situation.”

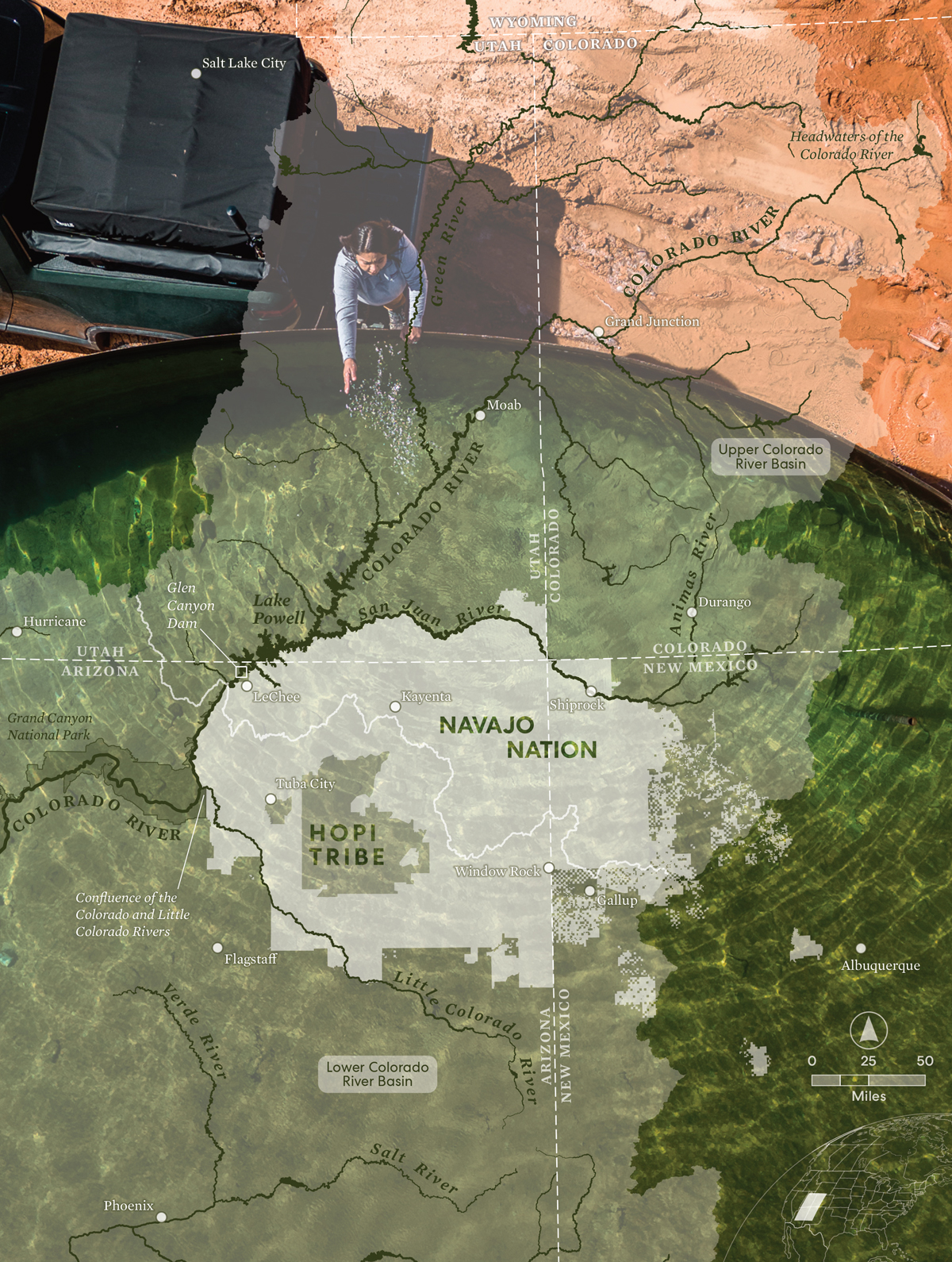

The Navajo Nation spans the borders of Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah, a semiarid region that gets between five and 25 inches of rain a year. The tribe’s water is mostly sourced from 20 aquifers—a finite and dwindling underground supply with a diminishing annual snowpack to recharge it. Additional water is drawn from springs, creeks, and the San Juan River.

But almost no water is drawn from the Colorado River. Although it passes through ancestral Diné lands, the river remains largely untapped by the tribe 174 years after the United States stole its land. (Only the Diné community of LeChee gets its water from Lake Powell.) Now, with water levels hitting record lows and more parties than ever sticking straws in the river, the Navajo Nation is facing off against the Department of the Interior in a Supreme Court case that legal experts say could shape the future of water use—and treaty rights—in the West.

WATER INEQUALITY IN THE UNITED STATES goes hand in hand with the dark legacy of colonization, systematic racism, and efforts to wipe out Indigenous cultures. For the Diné, it began with a treaty signed with the US government in 1849 that placed the nomadic tribe “forever” under the “exclusive jurisdiction and protection” of the United States, which included the promise of establishing a reservation. Instead, starting in 1863, the US cavalry forced 10,000 Diné to walk 400 miles from their homelands to a concentration camp at Bosque Redondo in eastern New Mexico, where they were detained for five years in an effort to eradicate their culture and language. In these “fearing times,” alkaline water caused crops to fail, water and firewood were scarce, and thousands of Diné died of dysentery, exposure, and starvation.

Water inequality in the United States goes hand in hand with the dark legacy of colonization, systematic racism, and efforts to wipe out Indigenous cultures.

When the Diné were released in 1868, they signed another treaty with the United States, Naal Tsoos Sani (“the Old Paper”), which formed the Navajo Nation and guaranteed enough water to sustain it. That promise was bolstered by the Winters Doctrine, after a 1908 Supreme Court ruling on tribal water rights. The doctrine established that the Navajo Nation has rights to the water that is necessary to fulfill the purpose of the reservation that the United States established for them, and that the United States has a federal trust responsibility to protect those rights.

Despite the doctrine, the Diné have struggled to regain access to their water. In 2003, the Navajo Nation sued, claiming that the US had breached that trust duty. Eighteen years later, the US Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit finally sided with the Diné. According to circuit judge Ronald Gould, federal agencies “have an irreversible and dramatically important trust duty requiring them to ensure adequate water for the health and safety of the Navajo Nation’s inhabitants in their permanent home reservation.” To the disappointment of many Diné, President Joe Biden’s Interior Department appealed the ruling to the Supreme Court, which heard the case in March.

Both sides of Interior v. Navajo Nation insist that understandings of the 1868 treaty at that point in time must be considered. The government contends that the main stem of the Colorado River should not qualify for the breach-of-trust claim because the Diné had not established that such trust duties existed. An amicus brief filed by the Diné Hataałii Association, an organization of over 200 Diné medicine men and women, argues that the case must consider how traditional Diné law interpreted the original treaty, which was drawn up while the Diné were under the duress of captivity and desperate to return home. The brief argues that the US has an affirmative duty to assess the Navajo Nation’s water needs and develop a plan to meet them, in keeping with Diné traditional obligations: Tó dóó dził diyinii nahat’á yił hadeidiilaa (“Water and the sacred mountains embody planning”) and Nitsáhákees éí nahat’á bitsé silá (“Thinking is the foundation of planning”).

Diné water-law expert Heather Tanana: “For the Supreme Court to take up this case is a little scary. No one can guess the outcome.”

During oral arguments, the US tried to avoid what the Supreme Court watchers at SCOTUSblog called “the default interpretative rules of Indian treaty construction, which strongly favor the Nation.” Instead, the US argued that the 1908 Winters Doctrine had granted the Diné a property right to water but that it wasn’t the government’s obligation to enforce it. Justice Neil Gorsuch, one of the court’s conservatives who is historically sympathetic to the protection of treaty rights, asked, “Could I bring a good breach-of-contract claim for someone who promised me a permanent home, the right to conduct agriculture and raise animals if it turns out it’s the Sahara Desert?”

The representative for the Interior Department expressed concern that a Navajo Nation victory in the case had the potential to limit the water available to other users in the drought-stressed Colorado River Basin, and that it would open up opportunities for other tribes to confront the federal government with similar cases. While a decision in favor of the Navajo Nation would not instantly resolve the tribe’s water woes, it would bolster the nation’s legal efforts, which have been at a standstill for decades. A decision in the case is expected this summer.

Diné water-law expert Heather Tanana, 40, is intimately familiar with the stakes of the case. When she was in middle school, her father, who worked for the Indian Health Service, accepted a job at IHS headquarters and moved the family from the Navajo Nation to the Washington, DC, area. “I saw the real disparity in education and infrastructure like roads and buildings,” she said. “It was my first time sensing not everyone is subjected to poor economic conditions like unreliable water.”

Until the Navajo Nation’s water is quantified, Arizona is making management decisions on water that is legally not theirs.

That unreliability affects the quality of life in Diné communities beyond the availability of drinking water. It limits agriculture, contributes to food insecurity, and delays the construction of essential infrastructure like hospitals. Seeing the effects of federal laws and policies on tribes, Tanana decided to follow her father in service to Native people by pursuing a law degree. But it was her family’s experiences during the pandemic that spurred her focus on water. “When COVID hit, my parents were living in Monument Valley, where high incidence rates were connected to lack of water,” she said. “This is directly correlated to the necessity of hauling water from community source points and thus not being able to take all the recommended CDC precautions.” (At one point in 2020, the Navajo Nation had the highest rate of COVID infection in the United States.)

The Navajo Nation spent $5 million in pandemic relief funds to increase watering points, waive water fees, and distribute disinfectant tablets. But the lack of safe piped water continues to be a health barrier for Diné communities. To address it, Tanana helped launch an initiative with several other tribal members and water experts called Tribal Clean Water, which pushes the federal government to address universal access to clean water for all tribes in the Colorado River Basin.

That objective is, of course, based on the government’s treaty and trust responsibilities as mandated by the Winters Doctrine, and Tanana was initially hopeful when the Ninth Circuit Court upheld it. “The government knew when they established these tribal lands that they didn’t have water and that they needed water to survive.”

That’s why she finds the Interior Department’s position that it has no obligation to provide the water so deeply worrisome. “For the Supreme Court to take up this case is a little scary, just because of everything else they’ve been doing in other cases,” Tanana said. “No one can guess the outcome with high certainty because they have shown they are willing to displace established precedent.”

Map by Anna Riling/Four Corners Mapping and GIS; Background photo: Mylo Fowler

THE UNITED STATES HAS GROWN and prospered by stealing not only Indigenous people’s lands but also their water. While the water rights of the Navajo Nation and 11 other tribes to the Colorado River remain unresolved, the river’s water continues to sustain and develop major southwestern cities. Or, rather, it did before the drought. In the past two years, Lake Powell, the second-largest reservoir in the United States, which harnesses the Colorado behind Glen Canyon Dam, has hit record lows. On a winter walk around Powell’s rim, which spans the Arizona-Utah border, former Navajo Nation water commissioner Leo Manheimer, 67, stopped to look down at the growing “bathtub ring,” the thick coating of white sediment on orange sandstone that marks the falling water level. “As for the lake, there is no middle,” he said. “It should be full and thriving, or it should be no more.”

During Manheimer’s childhood in Shonto Canyon, Arizona, his family didn’t have a car. Instead of hauling water, they collected it from nearby potholes and built earthen dams to capture rainwater for their farm. When he tended his family’s sheep in the surrounding canyons, he never carried water with him. “I knew where all the springs and potholes were,” he said. Manheimer fears that such knowledge will be lost in the shift from traditional lifestyles to a more consumer-driven economy, and with it wisdom about how to adapt to climate change and drought.

Much of Manheimer’s traditional knowledge about the region was gleaned from Diné medicine man Buck Navajo, who was born in 1919 and lived to be 103. Among the massive changes to the landscape that Navajo witnessed was the completion of Glen Canyon Dam in 1963. The Colorado River backed up for 186 miles, flooding Glen Canyon, its tributaries, and many cultural sites of deep significance to form Lake Powell. When Navajo crossed the river to hunt and gather herbs, Manheimer said, “an offering was made at the river, thanking the gods and the deities for success and safe travels.” All that changed after the lake came up. “The lake affected grazing, farming, and the gathering of sumac, a plant harvested to make baskets and water jugs.”

According to Buck Navajo’s teachings, the construction of Glen Canyon Dam caused direct environmental and cultural harm. Manheimer said, “[He] talked a lot about the balance of life and how things need to be in sync, in terms of seasons, with animal and human life. There must be balance in weather, and that balance is dependent on the two major rivers, the San Juan and the Colorado. The birthplace of moisture is at the confluence of these two rivers. He taught that this balance was interrupted when Lake Powell flooded the confluence. The lake is receding because the confluence is teaching us all a lesson through the extreme drought.”

APART FROM the Interior v. Navajo Nation ruling, the fate of the Colorado River lies with the seven states that depend on its water—Arizona, California, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming—the signatories to the 1922 Colorado River Compact, which governs the distribution of its waters. Unfortunately, this “law of the river” was drawn up during an abnormally wet period in the Southwest and neglected then-available scientific data pointing to the region’s past prolonged droughts; it over-allocated the water in the river even at its highest flows.

Also ignored by the 1922 compact were the Indigenous peoples who have been stewards of these waters for millennia. In 1963, tribal water rights for reservations adjacent to the Colorado River in Arizona, California, and Nevada were reaffirmed by the Supreme Court in Arizona v. California, but the court blocked the Navajo Nation from intervening, citing the federal government’s role as the trustee of the tribe’s water. While the case defined and recognized tribal water rights as senior to states’ rights, the Navajo Nation wasn’t among the four Arizona tribes whose water rights were quantified as a result of the decision.

In recent years, water levels in Lake Powell and Lake Mead have dropped so low that they risk falling below the minimum level to spin the Glen Canyon Dam’s antiquated turbines to generate hydropower. If levels fall below that, the reservoirs will hit “dead pool,” meaning that no excess water could escape through the dam’s outlets, drastically reducing the water supply for people in Southern California, Arizona, Nevada, and Mexico as well as tribal nations. LeChee and the city of Page, Arizona, have already successfully pressed the Bureau of Reclamation to construct a new outtake tube in the dam, allowing water to be drawn from 100 feet below the current dead pool level.

Last winter’s significant precipitation and snowpack may stave off a worst-case scenario, but to move either reservoir out of long-term danger would require many such winters. Even in recent years with close-to-average snowpack, runoff has been weakened by higher average temperatures and dry soils sucking up the moisture. According to Seth Arens, a climate research scientist for Western Water Assessment, the highest Colorado River runoff years were 1983 to 1986—which happened to be one of the wettest four-year periods in the past 1,200 years. He estimates that even with a similar sustained period of record precipitation, the reservoirs would both still be 7 million acre-feet below capacity. (An acre-foot is enough to supply two or three US homes for one year.) It is unlikely, he said, that Powell and Mead will ever fill completely again.

To prepare for a more arid future while maintaining these two major reservoirs, the Biden administration pressured the Colorado River Basin states to come up with a plan to cut water usage by 15 to 30 percent on top of water reductions made in 2007 and thereafter, but they failed to agree. The Interior Department stepped in with a Solomonic alternative: to spread the cuts evenly among Arizona, Nevada, and California. Finally the states agreed to collectively cut their water use by 3 million acre-feet over the next three years. In exchange, the states will receive $1.2 billion from the Biden administration as part of the Inflation Reduction Act. The deal will only be temporary, and the states will reconvene in 2026 to make bigger and more lasting changes to how they use the Colorado River.

But from the Navajo Nation’s perspective, until its share of the river is determined—likely to fall somewhere between 2 million and 5 million acre-feet a year—other entities will be using their water. “It’s almost an incentive for tribes’ water rights to not be resolved,” Tanana said. “A lot of the tribes tend to have senior water rights that would get priority if they were able to utilize them.”

This is in part why Interior v. Navajo Nation carries so much weight. “Many people have talked about the need for certainty in the Colorado River Basin and settling outstanding water rights,” Tanana said. “This case has the potential to add to the chaos and confusion.” Until the Navajo Nation’s water is quantified, the entire state of Arizona is making management decisions on water that is legally not theirs.

That will change, however. Negotiations over the future management of Lake Powell and Lake Mead, slated to take place in 2026, are beginning to ramp up, and this time, all 30 of the region’s tribes have been invited to participate. Tulley-Cordova looks forward to the negotiations and to sharing her research and knowledge: “We can’t wait for people to create that seat at the table. We have to propose solutions, propose opportunities that we’re willing to participate in to meet our needs.” Tanana is confident that the inclusion of Indigenous perspectives will be part of the long-term solutions for the changing climate and water conditions. “The Navajo Nation, like many [Colorado River Basin] tribes, has traditional teachings about balance,” she said. “For Navajo, the concept of Hózhó means that we must be in balance with ourselves, with our community members, and with the environment. When something gets out of balance, bad things happen.”

The Navajo Nation needs more than paper rights to Colorado River water. It also needs what are known as “wet rights”—settlements that require states or the federal government to provide tangible access to water through the necessary funding and infrastructure. The 2022 Utah Navajo Water Rights Settlement, for example, solidified the Diné’s right to water from aquifers, the San Juan River, and Lake Powell and also granted $210 million in federal funding and $8 million from the State of Utah for drinking-water infrastructure. A 2009 agreement with New Mexico allots the Navajo Nation water from the San Juan River and Cutter Reservoir; some water supports Diné agriculture, while the remainder will eventually be piped 300 miles to the eastern portion of the Navajo Nation and the Jicarilla Apache Nation via the Navajo-Gallup Water Supply Project.

Every day as Tulley-Cordova drives to work, she passes the pipeline construction. In February, the Interior Department announced that it would use $580 million, mostly from President Biden’s Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, to fulfill water rights settlements with 12 tribes. Included is $137 million for the Navajo-Gallup pipeline and $39 million for drinking-water infrastructure.

Money is essential to water security in the Navajo Nation, but Tulley-Cordova maintains a Diné perspective on the Colorado River: “How do you place a value on something that’s so special to you, that you want to pass on for generations?”

IN SEPTEMBER 2022, Tulley-Cordova joined three other Diné scientists on a 280-mile field study of the Grand Canyon between Lees Ferry and Lake Mead, looking especially at non-runoff contributions to the river. “Sometimes people only attribute flows in the Colorado River to precipitation events, like snowmelt runoff,” she said. “But there is a major contribution from groundwater, including springs.”

It was Tulley-Cordova’s first float through the Grand Canyon. She said the journey made her reflect on how the water propelling her downriver—much of it sourced from the Navajo Nation—united landscapes, people, and wildlife, upstream and downstream, across the Southwest. The problems facing the Colorado River go beyond human consumption. If water levels fall below dead pool in Lake Powell, it would sever the Grand Canyon and all its wildlife from their primary water source. Rafting down the river, she said, “may not be a possibility of the future.”

An important stop during the Grand Canyon trip was at the confluence of the Colorado and Little Colorado Rivers. According to Diné stories and teachings, it is more than just the geographic uniting of two waterways. It is a sacred place, home to Diné deities, a place for prayers and offerings. “I felt a spiritual connection that has extended for millennia in the region,” Tulley-Cordova recalled, “to know where we are in our land as Navajo people—to fully understand the significance of where we are as a people.”

At the confluence, Tulley-Cordova saw monsoonal runoff form ephemeral waterfalls and transform beaches with rockfall. The Little Colorado’s typically turquoise waters ran a muddy brown—river sediment temporarily churned up by a storm. “I knew that meant it was raining somewhere upstream on the Navajo Nation,” she said. “That water was coming down to meet us at the confluence.”

This story was made possible with funding from The Water Desk, an initiative of the Center for Environmental Journalism at the University of Colorado Boulder. It was launched in 2019 with support from the Walton Family Foundations with a mission to increase the volume, depth, and power of journalism connected to Western water issues.

This article has been updated since publication.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club