The Origins of Glamping: 1902 Sierra Club Outing

July 1, 2014

With caravans of McMansion RVs hogging the Friday afternoon highways, gourmet s’more kits from Etsy, and limitless hot water at campground showers, perhaps you feel nostalgic for the good old days when camping stripped away the trappings of society and offered union with raw nature. If so, don’t look to the Club Outings of the early 20th century for romanticized visions of roughing it. Sierra Clubbers were the original glampers, experiencing the great outdoors without sacrificing luxury. As the 1902 4th of July King’s Canyon outing announcement proclaimed: “The object of this trip is to lighten (as materially as possible) the burdens ordinarily incident to camping and thus afford an exceptional opportunity for visiting the High Sierra with a maximum amount of ease and comfort.”

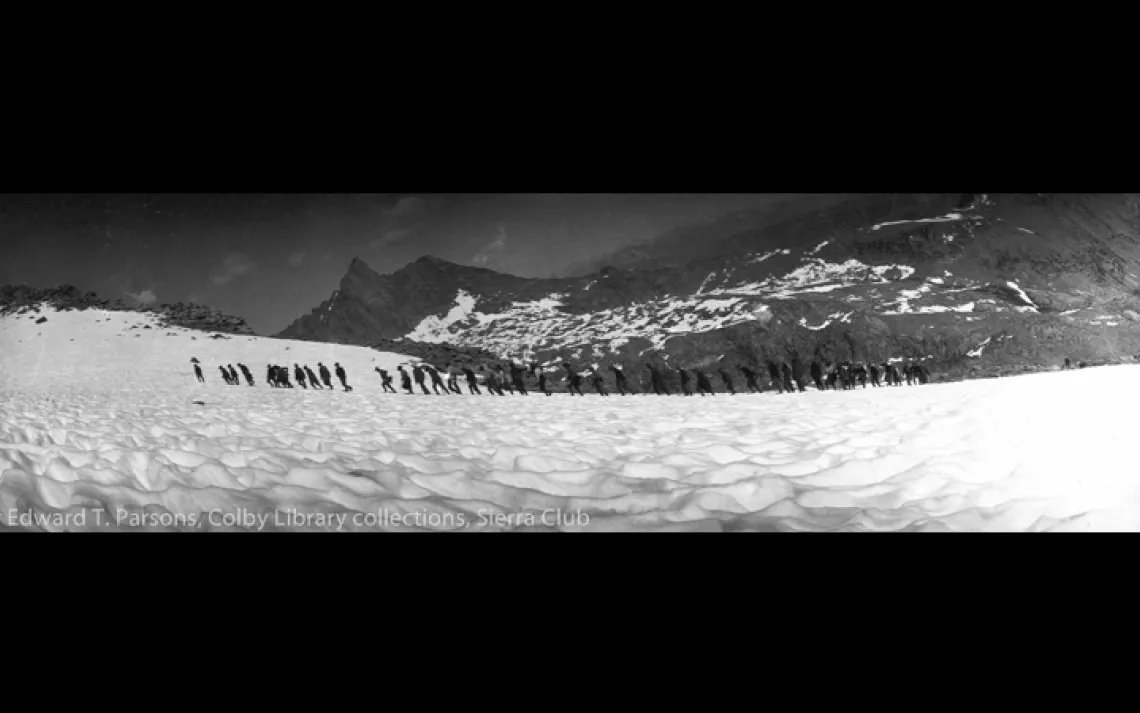

Ascent of Mt. Brewer, Second Sierra Club Outing, Kings River, 1902. By Edward T. Parsons.

Attention Cinderellas of the High Sierras: hem your gowns. The 1902 pamphlet suggested skirts “not more than half way from knee to ankle.” For female equestrians, the pamphlet recommended divided skirts or “the costume described by Mrs. Seton-Thompson in her book entitled A Woman Tenderfoot,” that is, a skirt with a doubled front. (Mrs. Seton-Thompson’s credentials included braining a rattlesnake with a frying pan while on a wolf hunt.) To maintain a complexion white as the peaks of Mt. Whitney, women were advised to wear heavy veils to protect from snow burn.

Group on University Peak (Mt. Whitney). On the left is Helen Gompertz, the photographer's future wife, with Estelle and Belle Miller, 1896. By Joseph N. LeConte.

As for the gentlemen, “tramping suits” of denim, corduroy, khaki, or "any stout material” were recommended. Nevertheless, haute couture of the High Sierras had to make concessions to the conditions of the excursion. Participants were advised that “one suit will be sufficient for the entire trip.”

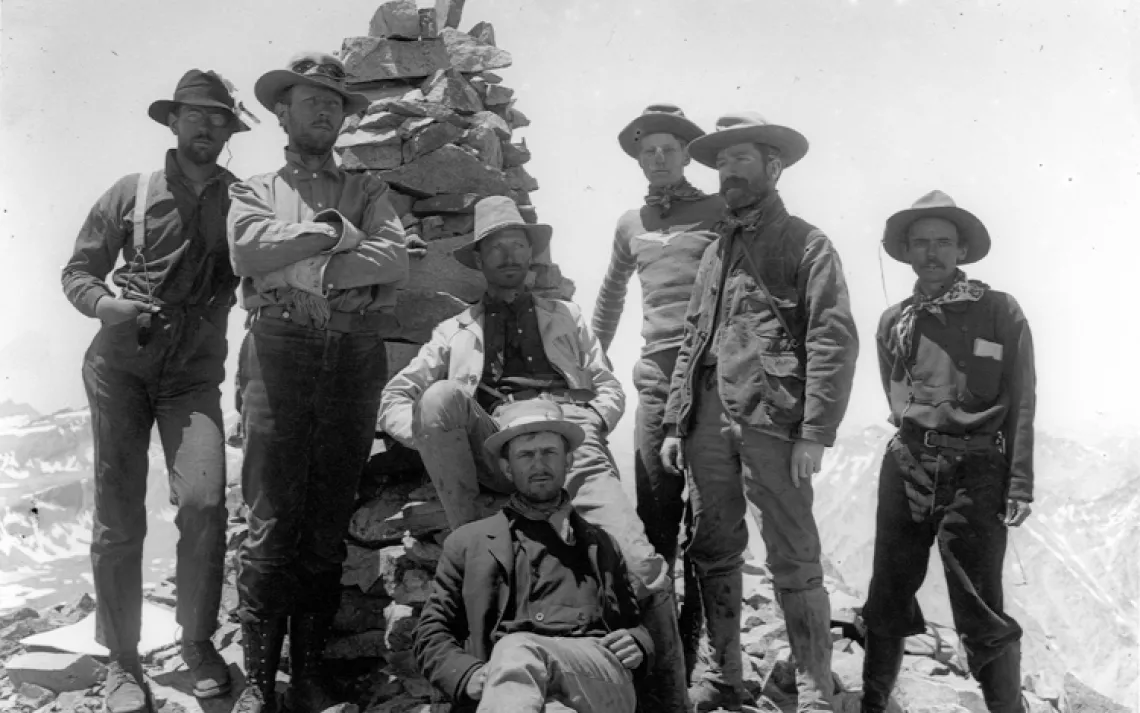

Group (first party) on summit of Williamson, Sierra Nevada, 1903. By Joseph N. LeConte.

After a day’s trekking through magnificent landscapes, photographers could lug their jugs of silver bromide to the darkroom provided by the Club and set up “at the camp in the Meadows.” Of course, all budding Ansel Adamses were required to “furnish their own chemicals and outfit.”

Group on the summit of Farewell Gap, Kern River Canyon outing, 1903. By Edward T. Parsons.

For the comfort of hungry trampers, the Club provided meals through its “commissary department.” This was no tinned wiener affair. The cooking was performed by a salaried head cook and assistants. But in the uncivilized wilds, even glampers had to lift a finger. Due to the lack of tables “for so large a party at such a distance from civilization,” and the desire to keep expenses down, when it came time to serve up the feast, the pamphlet requested “the members of the party render themselves some slight assistance.”

Serving dinner, 4th of July 1902 at Kings River. By Joseph N. LeConte.

In the five-star banquet hall beneath the stars, the pamphlet promised that “knife, fork, spoons, plate, cup and two saucers will be furnished each member participating in the advantages of the commissary, and those desiring a more elaborate outfit will be required to furnish it.” Research is ongoing as to whether the spoons in question included an Absinthe and Five O’Clock spoon, or whether gourmandes had to tote the family silver through the canyon themselves.

Hungry Sierrans, Mineral King Valley, 1903. By Joseph N. LeConte.

They may have eaten more sumptuously and dressed more fashionably, but the Sierra Club adventurers of 1902 escaped to the mountains for the same reasons we do: “On expeditions of this kind...perhaps a week elapses before they feel fully tuned up, especially if they are at all run down at the start.” Of course, daily doses of hiking, campfire songs, and Floradora dancing are most salubrious when taken according to the pamphlet’s detailed prescriptions: “Both for enjoyment and for health, it is advisable to stay away at least two weeks, if possible, and, better still, four, or even six, if one’s time and means permit.” Perhaps we should take their advice on healthier living and carve out a few weeks to spend in this wilderness this summer.

The Floradora dance, Sierra Club outing in King's River Canyon, 1902. By Joseph N. LeConte.

Lucia Iglesias is an editorial intern at Sierra. She studies Literary Arts and German Studies at Brown University. She has been described as "eating the brontosaurus diet [vegan]," "a ninja spider who does aerial arts," and "like the overgrown Victorian brambles."

More articles by this author The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club