Backcountry Bookshelf

A suggested reading list for the National Park Service centennial.

Photographs by Lori Eanes

Backcountry adventure and book reading aren’t exactly the most compatible of pastimes. Paper books come with the obvious problem of weight. It’s a pain to lug around the bones of dead trees and, as any veteran backpacker knows all too well, the ounces add up to pounds, and the pounds to miles. A lightweight Kindle or similar e-reader can be a good workaround, but there’s always the risk of damaging the equipment. E-readers also come with a kind of range anxiety. If you’re on a long journey, the batteries might crap out mid-trip.

Still, when I make a foray into the wilderness, I insist on bringing along reading material. There are few things finer than sitting riverside in the company of a writer who has already plumbed wild nature. Some of my fondest memories involve loafing on the banks of the Hoh River reading former Supreme Court justice William O. Douglas’s My Wilderness, and lounging under a ponderosa pine with Annie Dillard’s mystic musings. Just like how a great novel makes a reader’s own quotidian experience seem deeper and more textured, literature’s insights can magnify a landscape.

This month marks the 100th anniversary of the founding of the National Park Service, and my desk is piled high with books timed for the occasion. Not all of these titles are meant to be wedged in your backpack. Some are geared for pre-trip planning, while others are better suited for the coffee table. Here are a few of the outdoors-themed books that I’ve enjoyed so far this summer.

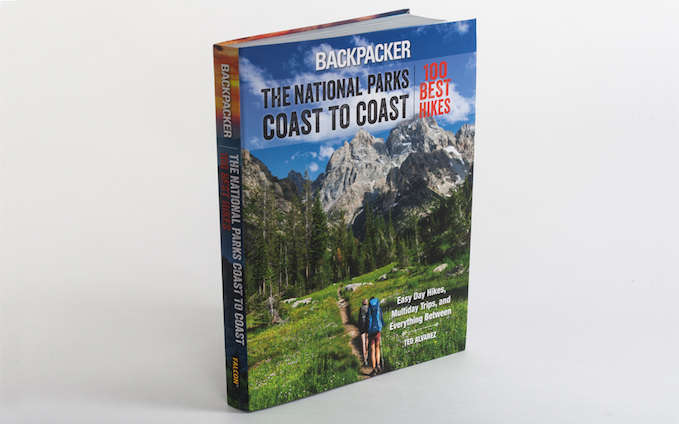

The National Parks Coast to Coast: 100 Best Hikes

By Ted Alvarez (with the staff of Backpacker magazine)

384 pages; illustrated; $26

Falcon

Smart planning is a prerequisite (if never a guarantee) for the perfect backpacking trip. Before you hit the trailhead, make sure to check out The National Parks Coast to Coast, a users’ guide to exploring the parks’ backcountry areas.

Author Ted Alvarez seems to have the best job in the world—hiking iconic routes then writing about them. This list of the 100 best hikes in the park system has everything you’d expect in a guidebook: detailed topo maps, hike routes described by landmarks and GPS coordinates, and basic dos and don’ts (how to ford a river, how to avoid conflicts with bears). Plus pages of nature porn. Trip suggestions for the most popular parks are nicely balanced between the bucket-list routes and treks that are off the beaten path. The Mt. Rainier National Park section, for example, includes a description of the usually packed Wonderland Trail, along with a plug for the “rugged and remote . . . rarely visited” Tatoosh Range.

The trail descriptions are accompanied by touching (if sometimes treacly) profiles of national park rangers, and classic backcountry yarns from Alvarez and his colleagues at Backpacker magazine. My favorite? Peter Frick-Wright’s tale of going off-trail for 10 days in Yellowstone, an experience that felt “electric” until days of “off-trail scrambling” left his body “feeling like it’s been processed by the forest’s digestive system.” That story and others will leave you itching for your next wilderness adventure.

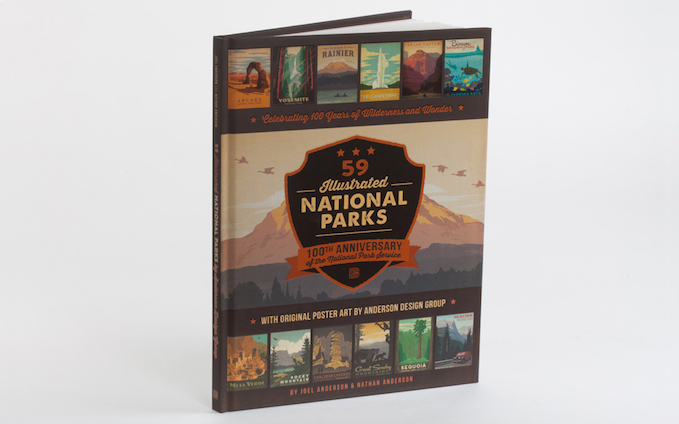

59 Illustrated National Parks

by Joel Anderson and Nathan Anderson

160 pages; illustrated; $50

Anderson Design Group

During the Great Depression and the early years of World War II, the Works Progress Administration commissioned artists, photographers, and writers to create works that would capture something essential about the American experience. The endeavor helped spark the careers of artists such as Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko, led to the creation of murals and other public artworks across the country, and funded the invaluable oral history Slave Narrative Collection. Less famously, the WPA underwrote the production of a series of travel posters featuring the national parks.

The images were almost lost to the dustbin of history until, in 1973, a seasonal park ranger at Grand Teton rescued some of them from a trash pile. Of the 14 parks posters originally created in the 1930s and ’40s, 11 designs remain with us today. Those images inspired Denver-based illustrator Joel Anderson and the designers at his firm to create new versions of the posters to celebrate the NPS centennial.

The new posters feature bold, romantic imagery—Old Faithful exploding into the sky, Crater Lake cloaked in snow—in a deliberately throwback style that echoes the vibe of the originals. You’ll find plenty of big mountains and tall trees, and lots of critters, too: bison, elk, caribou, coyotes. Anderson and his team do an expert job of conveying the timeless thrill of the parks. This is nostalgia put to wise use; it’s propaganda for a good cause.

The 21st-century posters depart from the originals in one key aspect: They often feature people in the scenes. Most often we see young couples (dressed in 1930s-era garb) enjoying an epic view. But there are parents with kids, a lone horseman in Bryce Canyon, a pair of kayakers navigating the Colorado River through the Grand Canyon. The human presence is a nice reminder that our national parks are a cultural treasure as much as they are a natural one.

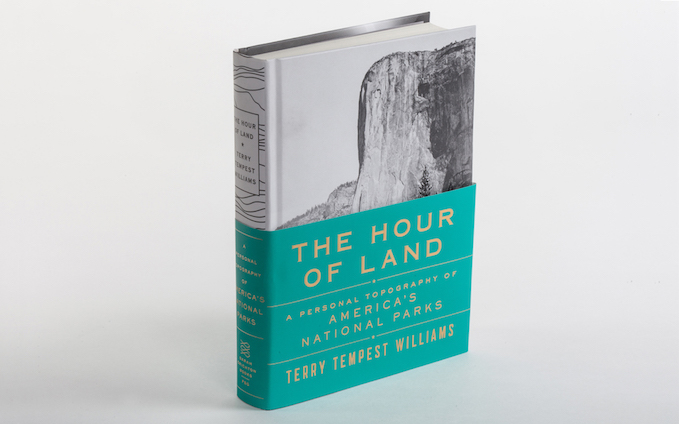

The Hour of Land: A Personal Topography of America’s National Parks

By Terry Tempest Williams

416 pages; illustrated; $27

Sarah Crichton Books/Farrar Straus and Giroux

“A Personal Topography of America’s National Parks” is the subtitle of Utah writer Terry Tempest Williams’s latest book, and, as you might glean from that line, this is a work of sweeping emotional ambition. Williams is a writer (and, I have to add, an individual) of preternatural grace, and with this book, her 15th, she demonstrates her signature emotional intelligence. She is hyper-attentive to the ways in which the natural world shapes her inner world and, at the same time, she’s alert to the thoughts and feelings of others, open to allowing those moods to shift her own.

The Hour of Land (the title comes from a Jorie Graham poem) is, in many ways, a love letter to the parks. Williams the naturalist and wilderness advocate is front and center. Rambling through Big Bend National Park in Texas, she writes, “I could walk forever with beauty. Our steps are not measured in miles but in the amount of time we are pulled forward by awe. This is another gift from our national parks, to be led by the vistas, to forget what nags us at home and remember what sustains us, the horizon.”

But she is also impatient with the hagiography that surrounds the parks. If the parks are, as Wallace Stegner famously said, “the best idea we ever had,” they are also, Williams argues, “an evolving idea.” The story of the national parks is complicated in the same way the larger American story is: an inspiring ideal that has been eroded by the realities of colonialism, slavery, and dispossession. Williams’s impassioned declarations are often counterbalanced by questions and uncertainties. “This is wilderness, to calm the mind,” she writes during a visit to Gates of the Arctic National Park in Alaska. And then, on the next page: “Who cares? Who cares about this wilderness? This glorious indifference?”

If this is a personal topography, it’s also a public one. Williams happily shares her own memories and stories of the national parks and then goes beyond her autobiography to offer other people’s voices—family, friends, friends now dead. There are cameos from bold-faced names such as Edward Abbey, Stuart Udall, and 21st-century-monkeywrencher Tim DeChristopher, as well as random park visitors like a military veteran roaming the wildlands, a scientist researching the impact of the BP blowout in the Gulf of Mexico, and many rank-and-file conservation activists. Her naturalist musings are matched with a sociologist’s curiosity. For every chapter about big, epic landscapes (Grand Teton, Canyonlands, Glacier), there’s one about a historic site (Gettysburg Battlefield, Alcatraz Island, César E. Chávez National Monument).

This is a kaleidoscopic book—a swirl of on-the-ground dispatches, journal entries, half-poems, reprinted letters, memoir, history. This seems to me a case of form following function, a way for Williams to communicate her larger point that the parks ideal is a refraction of every visitor’s unique experience. “The perspective we are given depends on the person telling the story—season by season,” she writes in her introduction to Gettysburg National Military Park. On one of the last pages, she then translates this idea into an image that has embedded itself in my mind: “Our national parks are a burning bush of identities.”

Engineering Eden: The True Story of a Violent Death, a Trial, and the Fight Over Controlling Nature

By Jordan Fisher Smith

384 pages; $28

Crown

The Hour of Land may be the most emotionally ambitious parks-related book of the season, but Engineering Eden is hands down the most intellectually ambitious. Jordan Fisher Smith (author of the well-regarded book Nature Noir) is out to make a point: Our ideas of what constitute “natural,” “unnatural,” and “wild” have always been contingent on the times, and when competing definitions of those concepts smash into each other, the clash can be deadly.

As evidence, Smith presents the story of 25-year-old Harry Walker, who in 1972 died from a grizzly bear attack in Yellowstone National Park. Yellowstone is, of course, the nation’s first congressionally created park and, in many ways, the ur-nature preserve—a place “developed late and saved early,” in Smith’s words, and therefore spared the ecological simplification that comes with domesticated landscapes. Walker’s unfortunate end was very likely due to the fact that the National Park Service had recently stopped the decades-long practice of feeding the region’s grizzly population. The Park Service’s decision to cut off the bears from food sources like the park’s landfill was part of an effort to naturalize the bears’ behavior—that is, to make them once again not reliant on humans. In hindsight, the experiment was a success; today, the grizzly population in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem is healthy and strong. But in the summer of 1972, the shift in park wildlife management policy was fueling increased bear-human conflicts. A hungry bear is also an angry bear.

Smith tells this story via a courtroom drama. After his death, Walker’s Alabama parents sued the federal government for negligence. The ensuing trial was not merely a judgment on the Park Service’s policies in Yellowstone; it also became a venue for debating how—and whether—humans should attempt to manage wild nature. Smith toggles between the Los Angeles courtroom and the plateaus and valleys of the Northern Rockies as he teases out the inherent tensions involved in any effort to control wildlife. Along the way, he profiles some of the giants of 20th-century conservation, including Starker Leopold (son of Aldo and an intellectual powerhouse in his own right) and Frank and John Craighead, idiosyncratic twins who, among other accomplishments, pioneered the use of radio collars for studying wildlife.

It’s a big ask for the reader—to keep track of all the characters, all of the scientific reports, all of the place names in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. But Smith pulls it off thanks to his command of the material, his firm grip on the narrative, and his insatiable inquisitiveness. When it comes to natural history, he knows his stuff, and he’s attuned to the ironies of wildlife management: “Yellowstone was a big rectangle, and the lives of elk didn’t manifest in right angles.” Important insights come without any showy fanfare: “A lot more thought had gone into how human beings lived with cows, horses, dogs, feed corn, and alfalfa than how they could live with wild animals and untamed land.” At its best, Smith’s writing is pungent. His re-creation of a grizzly attack on a hiking party, for example, is cinematic and adrenaline-packed, and left me sweating: “The animal pulled her down, bit and clawed her, and dragged her, screaming, by one of the legs into the woods.”

Engineering Eden is anything but a straightforward story—and that’s what makes it a good one. In the end, Smith has the sense not to offer any neatly tied up lessons, and, instead, insists that remaining open-minded about how best to arrange human-wildlife relations is probably the most we can hope for. “How much should we respect nature’s autonomy? How much should we try to manipulate and control it to save it? . . . These are more useful as questions . . . than any answer we can give today.”

On Trails: An Exploration

By Robert Moor

336 pages; $25

Simon and Schuster

The best outdoors book of the year has nothing at all to do with the NPS centennial, but it’s an outstanding work that should be read by anyone who has spent time following a footpath through the woods. Robert Moor’s debut book, On Trails, trips through natural history, anthropology, gonzo reporter’s adventures, and memoir in a ramble that unpacks the many meanings of the routes we humans and other animals sketch on the land. “To deftly navigate this world,” he writes near the start of the book, “we will need to understand how we make trails, and how trails make us.”

Moor covers a lot of ground, both physical and intellectual, during his exploration of the idea of trails. There’s a whole chapter on the first creature to figure out locomotion—the Ediacarans, a part animal, part vegetable critter that lived at the bottom of ancient oceans and which has left us fossilized tracks “like a poem carved into a handrail at the Louvre.” There’s a long piece on the trails blazed by animals. Moor shows that elephants and ants alike are ecosystem engineers that shape “the earth as a collaborative artwork of trillions of sculptors.” There’s a short history of European colonization of North America told via the story of the Appalachian Trail.

Trails are an esoteric topic in the epoch of the interstate, when so many moderns have never experienced what Moor calls the “elemental bond between foot and earth.” But Moor has no problem keeping his subject alive. The prologue alone is worth the price of admission: a nearly-30-page set piece about hiking the A.T. that puts Bill Bryson and Cheryl Strayed to shame. (Moor actually, you know, completed the full thru-hike.) Throughout, Moor balances an impressive erudition with an easy self-deprecation. He’s not afraid to admit the many times he’s gotten lost.

I especially appreciated Moor’s sensitivity to the indigenous experience, his recognition that we can’t understand humans’ marks on the earth without knowing the preindustrial chapters of our species’ story. Moor spends a lot of time among the Cherokee and the Creek and their descendants, trying to trace back the pre-Columbian tracks that once crisscrossed the southeastern United States, a trail network so dense that it was tricky for Europeans not to get lost among all of the crossroads. He goes as far as Borneo, where he walks Paleolithic trails that are an “inscription that predate(s) writing and even the spoken word.” Trails, he finds, are traditional cultures’ way of remembering topography by affixing meanings to places.

In the Google Maps era, this kind of intelligence is endangered. How few of us still structure our memory spatially (rather than chronologically), like everyone did for millennia, like those who live with the land still do? Moor’s book is a testament to the importance of retaining our species-old relationships to dirt paths and cairn-ways. Trails connect us to the living earth. They are reminders that many routes are possible, that we will find unexpected detours, and that “the so-called modern world is not all of humanity’s manifest destiny.”

To be sure, Moor meanders. (I could have lived without the line, “Metals were mined, oil drilled.”) But he never goes astray. On Trails delivers on the promise of any good trail: It takes you to some wonderful places.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club