Wyoming's Great Disconnect

The state's political leadership doubles down on coal while the industry flounders

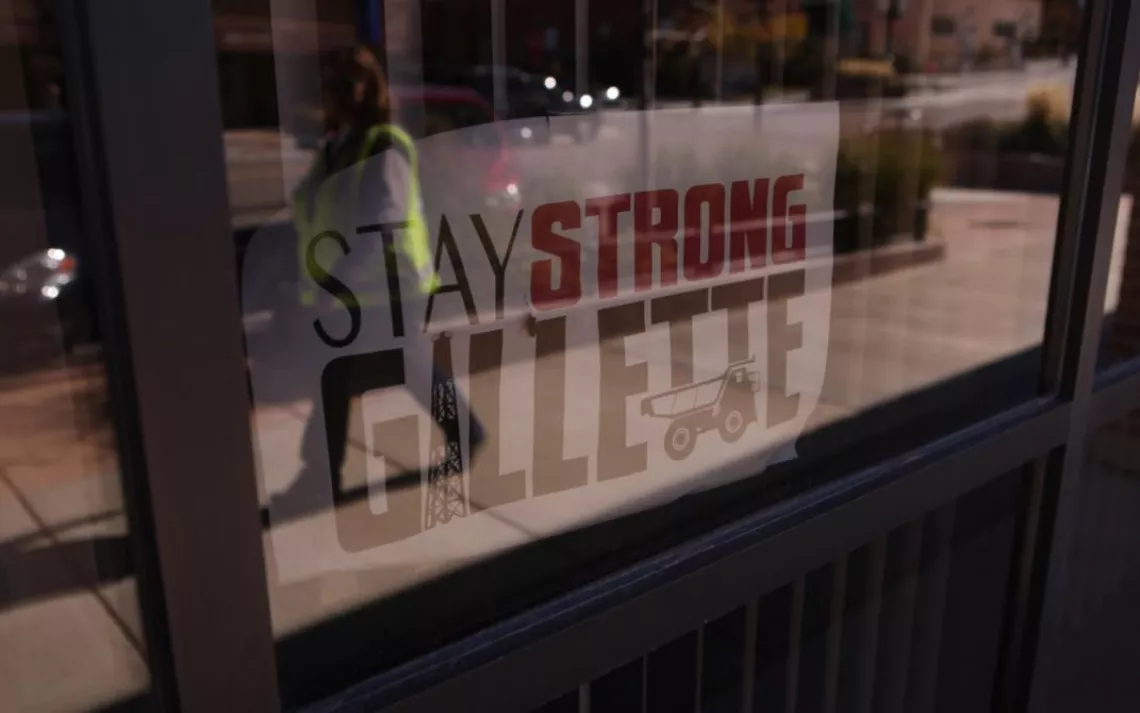

Sign in downtown Gillette, Wyoming | Photo by Toby Brusseau

The last day of March 2016 was "Black Thursday" in Wyoming's Powder River Basin. The two largest coal mines in the United States announced massive layoffs, sending shock waves through the industry. Peabody Energy laid off 235 workers at North Antelope Rochelle, and Arch Coal let go 230 workers at Black Thunder. The numbers amounted to about 15 percent of the workforce at each mine.

In response, Wyoming governor Matt Mead hastily called a press conference.

"Coal, as you know, has been facing an uphill challenge for some time," he said, looking somber. He blamed the situation on a string of unseasonably warm winters and an abundance of natural gas, and blasted environmental regulation for making it worse.

Nevertheless, the state of Wyoming would not be giving up on coal. The governor cited his administration's record number of lawsuits against the federal government, increased funding for "clean coal" technology, and efforts to expand markets through coal ports on the West Coast.

At a public hearing in Casper a month and a half later, the governor spoke more forcefully.

"[The Obama] administration is pursuing an unrealistic vision of a world without coal. Instead they should pursue a realistic vision that recognizes coal's place in the world and should invest to make it better."

"Coal supports Wyoming; Wyoming supports coal," he concluded. "Coal supports the United States; the United States should, too, support coal."

Townhouses in Gillette, Wyoming | Photo by Toby Brusseau

The layoffs last March were just one symptom of widespread problems besetting the industry. Coal's share of U.S. electric power generation has fallen from about 50 percent in 2007 to approximately 33 percent today, and the industry's gross earnings fell by 25 percent in 2015 (see "The Coal Industry Is Bankrupt"). At least five major coal producers have declared bankruptcy within the last two years.

But instead of weaning the state's economy off coal revenues and helping workers transition to new industries, state officials are holding fast to climate change denial and are staking the state's future on the pipe dream of a coal revival.

In an age of changing markets and changing climate, coal has arrived at its moment of truth. In Wyoming, perhaps no place better illustrates what this means, for the industry and for those whose livelihoods depend on it, than the city of Gillette.

In the northeast corner of Wyoming, on Interstate 90, sits one of the classic coal boomtowns of North America. With a population of just over 30,000, Gillette has the anodyne feel of any U.S. suburb: big-box stores, fast-food franchises, and motel chains. But head north a few miles along Highway 14 and turn up Highway 59 and the scene quickly changes from scattershot subdivisions to devastated earth in the Powder River Basin.

Here, the treeless, windswept plain has been opened to excavation on a massive scale. Gargantuan seams of coal stretch in all directions. Carbon dust swirls in the sky as industrial dump trucks the size of two-story buildings haul black ore out of pits that could easily house several sports stadiums.

Truck at a Powder River Basin mining operation | Photo by Todd Wilkinson

About 85 percent of coal mined on federally leased land—about 388 million tons' worth annually—comes from this area. Low-sulfur coal shipped out of the Powder River Basin has been burned at power-generation facilities in 34 states and beyond.

Flip on a light switch, turn up the air conditioner, or plug in a cellphone and it's possible you have Powder River coal going up a smokestack to thank, says Gillette mayor Louise Carter-King. She sees coal as an engine that has made unparalleled contributions to her town and state, and to the country. In her downtown office, the carpet declares Gillette "the energy capital of the nation."

In 2015, Wyoming's 18 coal mines employed about 6,500 workers. That may not seem like a lot on a grand scale, but the state's population is just under 600,000, and coal jobs are among the best paying in the state (Wyoming coal miners take home an average of $82,000 a year, twice the statewide average). Those jobs have tremendous ripple effects on the state's economy. According to estimates, each coal-industry position results in three additional jobs.

The coal industry also contributes over $1 billion annually to Wyoming's state and local governments. According to the Center for Energy Economics and Public Policy, about one-third of this revenue goes to education, from kindergarten all the way through to the community colleges and the University of Wyoming. The assertion that Wyoming kids are schooled on coal is not off the mark.

Signs of prosperity in Gillette are everywhere: the state-of-the-art recreation center with its six-lane indoor track and a 42-foot climbing wall designed to resemble nearby Devils Tower National Monument; the boutique shops downtown (including the cupcake store that serves a chocolate-on-chocolate concoction called Coal Seam Overload); the trucks, campers, and boats that sit in driveways. Carter-King's office is housed in a complex built with proceeds from fossil fuel revenue.

But that revenue is dwindling along with the coal industry. Between 2008 and 2012, coal production in Wyoming fell by 17 percent. Exports of coal from Wyoming to foreign markets are down more than 50 percent from 2007 numbers. The U.S. Energy Information Administration estimates that in 2015 overall U.S. local production dropped 10 percent, to the lowest annual level since 1986.

Intersection in Gillette, Wyoming | Photo by Toby Brusseau

The state's government has no alternatives readily available to offset this revenue loss. Wyoming doesn't have a corporate or individual income tax; instead, it depends on royalties and taxes generated from coal production.

The hammer has fallen hard as a result. In June, Governor Mead announced that the state budget would be slashed by $248 million. The Wyoming Department of Health will have to cut its budget by $90 million over the next two years. Education also took a hit: The University of Wyoming is expected to trim $35 million and community colleges $20 million from their budgets. More cuts are anticipated in 2017.

During his Black Thursday press conference, Governor Mead expressed sympathy for the coal workers who had lost their jobs. "When we have a natural disaster," he said, "we put together the appropriate team to respond to it. This isn't a natural disaster, but it's certainly a disaster in the lives of the miners."

The team he had assembled to address this crisis included the head of Wyoming Workforce Services, which is tasked with helping miners find new employment. But in fact, Governor Mead had just recently signed a two-year budget that cut $750,000 from that same agency.

Perhaps more than any other city in Wyoming, Gillette is feeling the pinch. In August, unemployment was at 6.8 percent, nearly double what it had been the year before (but an improvement from a peak of 8 percent that lasted five months). Workers are leaving to find jobs elsewhere. In March, there were 417 houses for sale, twice the number from the previous March. By August, that number had crept up to 553. Faced with a significant loss of sales-tax revenue, the city has reduced retirement benefits for its employees and eliminated city jobs. Last fall, 1,000 fewer students showed up on the first day of school—their families, presumably, having packed up and left town.

Carter-King says that some people feel forgotten. She acknowledges that an overabundance of coal has mostly caused the downturn but believes that the bad rap coal has received from the media and environmentalists has also played a part. She condemns tightening environmental regulations and what she sees as an attitude of hostility toward coal by President Barack Obama and then-presidential candidate Hillary Clinton. As evidence, she cites a sound bite—carefully edited and relentlessly played by Fox News—of Clinton saying, "We're going to put a lot of miners and coal companies out of business."

But Carter-King refuses to talk about Gillette in terms of doom and gloom.

"We haven't given up hope that we can get our coal economy back on track."

Louise Carter-King, mayor of Gillette, hasn't given up on the coal economy. | Photo by Toby Brusseau

Anger runs high in Gillette and across Wyoming toward what many see as the federal government's "war on coal." But regulations didn't sink the coal industry.

Mark Haggerty, a policy specialist at the nonpartisan research center Headwaters Economics in Bozeman, Montana, says the shift away from coal has been driven as much by the energy market and a glut of natural gas as by EPA mandates for old power plants. With new technology like fracking yielding huge quantities of cheap natural gas, coal has suffered. When gas prices are low, coal production drops, and it's unlikely to change, Haggerty says.

It's not only that natural gas has surpassed coal as America's main source of base electrical power; renewables—namely wind, solar, and hydropower—are gaining market share and becoming ever-cheaper alternatives. Powder River coal, despite its abundance, will only continue to decline in attractiveness over time.

In early 2016, the Bureau of Land Management, which governs coal leasing on 570 million acres of public land, announced a three-year moratorium on new leases. Industry and state officials said it was yet another example of the Obama administration's war on coal. But Rob Godby of the Center for Energy Economics and Public Policy says that few companies could have bid anyway because there was no viable market for coal—and environmental policies, he says, weren't to blame.

"The EPA's Clean Power Plan hadn't even gone into effect prior to Black Thursday, and neither have the actions spelled out in the Paris climate accord. Without regulation, coal's outlook is still bleak."

Godby points out that federal environmental regulation was one factor that brought 40 years of good times to the Wyoming coalfields in the first place. Beginning in the early 1970s, clean-air legislation and subsequent amendments passed by Congress mandated that coal-fired power plants switch to low-sulfur coal in order to reduce nitrogen oxide and sulfur dioxide emissions, which were causing the acid rain harming lakes and forests in the Northeast and Canada. The Powder River Basin has low-sulfur coal in epic abundance. And by a quirk of geology, it's located near the surface, making it easy and cheap to access and requiring far less labor to extract than the coal in the underground shafts and mountains of West Virginia, Kentucky, and neighboring states.

With demand and revenues now falling, Governor Mead has made a desperate attempt to revive the industry by trying to get new coal ports opened in the Pacific Northwest.

The chance of that happening? "Zero," Godby says. "China and its neighbors have a lot of coal available in the region, and getting Wyoming coal over there, given the low margins of potential profit, is way too cost-prohibitive. Plus, Washington and Oregon have made it clear they don't want to be pass-throughs for coal." (The Sierra Club's Beyond Coal campaign has helped by working to move states like Washington and Oregon off coal-fired power while strengthening their commitment to renewable energy.)

Governor Mead's commitment to coal is looking increasingly like a bad bet. Coal is not going to disappear overnight, but for the first time in history, the deck is stacked against it.

In Wyoming, doubling down on coal usually means doubling down on climate change denial.

Amiable senior geologist Dave Olson of Alpha Coal's Eagle Butte Mine flat out dismisses any cause-and-effect link between anthropogenic climate change and burning coal. He speculates that the average temperature in the Powder River Basin 60 million years ago was in the high 80s. The United States, he says, has no good reason not to exploit an abundant resource. Olson is smart and speaks eloquently about the subterranean strata shaping the landscape, but he voices a refrain common among the citizens of Gillette: The climate has always been changing.

Not like this, though: A June 2015 research study found that, compared with data from 1972 to 1999, snowpack in the Wind River Range—home to one of the largest concentrations of glaciers in the Lower 48—is melting 10 to 16 days earlier in the 2000s. Much of the state has been in moderate-to-severe drought since 1999.

Even though Governor Mead identified unseasonably warm winters as one reason for the declining fortunes of coal, he still does not acknowledge the reality of climate change—demonstrating a kind of mental gymnastics common among state officials that in turn infuses public dialogue across Wyoming.

In 2011, British landscape artist Chris Drury built an art installation titled Carbon Sink: What Goes Around Comes Around on the University of Wyoming campus. Logs from pine and spruce trees killed off by exploding bark beetle populations encircled a large pile of coal. In an email to a university official, the president of the Wyoming Mining Association, Marion Loomis, asked, "What kind of crap is this?" Other industry representatives and state legislators complained about the sculpture, and in May 2012 it was removed. The coal was burned for heat.

In 2014, the Science Standards Review Committee was prevented by the legislature from adopting national science standards for Wyoming schools because of the way climate change was presented. The standards were finally adopted last September.

And in 2015, some members of the school board in Cody sought to have references to climate change struck from textbooks altogether. The proposed action attracted condemnation not only from high school students but also from one of Wyoming's elder statesmen, Cody resident and former U.S. senator Alan K. Simpson, a Republican.

Simpson listened patiently to more than six hours of spirited community debate in which board members said that teaching lessons about climate change was a betrayal of the fossil fuel industry. Then he weighed in.

"There is climate change," he said. "It is real. I don't know what the hell it's all about, but I know man is a part of it, and anybody who sends someone out of this school system saying that it's a hoax is goofy."

"Climate change is the most partisan issue there ever was, which is bizarre because the knowledge of it is based on science, logic, and common sense that one side continually rejects," says Bob LeResche, the board chairman of the Powder River Basin Resource Council. He and his wife have a ranch near Sheridan and lease it out for irrigated hay and for cattle. His wife raises and sells heirloom vegetables.

LeResche has traveled to Gillette to testify at public "listening sessions" hosted by the Department of the Interior both on the temporary moratorium on leasing federal coal tracts and on tougher emissions standards for CO2 and other pollutants. He's also pressed the Interior Department's Office of Surface Mining to conduct a comprehensive review of environmental impacts, which has never been completed.

"When I testified once in Gillette," he says, "I said that I was a father and had lived in Alaska, where climate change is melting the permafrost away beneath people's feet. As I was speaking, a person screamed and called me a liar. . . . There is a huge disconnect. I've never seen a state so captive to the companies that do business there."

Don't blame workers for being worried about their kids and their mortgages, LeResche says. "Many of them moved to Gillette to work in the mines because they thought it was a way to a better life. They . . . feel cheated out of security they thought they had. But really, they are pawns. Their corporate employers, for whatever reason—probably their own greed, maybe their arrogance in the way they've controlled the political discussion in Washington, D.C.—have never accepted reality. And so they have treated the transition as something that would never happen. The reality is that because of market forces and the need to change how energy is produced, coal is going away."

LeResche says that the longer Wyoming stalls, the worse it will be for the state. "The past is gone. Wyoming has really been given an opportunity. It can emerge as a leader and get off its budgetary addiction to coal, or continue to fight against a future it can't stop."

Wendy Becktold provided additional reporting for this feature.

This article appeared in the January/February 2017 edition with the headline "The Great Disconnect."

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club