Under the Gun: An Investigation Into the Murder of Berta Cáceres

Honduras is the most dangerous country in the world to be an environmental activist

Photos by Mónica González Islas

Update:

On Friday, June 30, men wielding machetes attacked Bertha Zúñiga—the daughter of slain indigenous environmental activist Berta Cáceres—as she and colleagues traveled a road in the Honduran countryside.

At around 2:30 pm on June 30, Zúñiga—along with Sotero Chavarría and José Asención Martínez, members of the coordinating committee of the Civic Council of Popular and Indigenous Organizations of Honduras, known by its Spanish acronym, COPINH—were traveling to COPINH’s offices in La Esperanza from a community meeting when three men brandishing machetes in the air tried to block the road.

The driver of the COPINH vehicle was able to navigate around them when a fourth man standing next to a black Toyota Tacoma threw a rock into windshield of the COPINH vehicle. That man then boarded the Tacoma and chased the COPINH car, at one point passing them and trying repeatedly to ram them off the road and over a precipice. The driver of COPINH’s vehicle was able to evade the assailant and allow the group to escape unharmed.

In a statement, COPINH said the attack was related to a water conflict in the communities of Lomas de San Antonio and Las Delicias, where the USAID-financed Hidroeléctrica Zazagua dam has, according to COPINH, shut off water supplies.

The attack against Zúñiga—who has been elected of the general coordinator of COPINH, the organization her parents co-founded—is a disturbing sign of the atmosphere of political violence and impunity in Honduras today.

In other news related to the murder of Berta Cáceres, the two main foreign banks financing the controversial Agua Zarca dam, Netherlands Development Finance Institution and Finnish Fund for Industrial Cooperation, recently announced that they are withdrawing their funding from the project.

Esta artículo está disponible en español.

GUSTAVO CASTRO WAS IN BED, working on his laptop, when he heard a loud noise. It sounded like someone was breaking open the locked kitchen door. From the bedroom across the hall, his friend Berta Cáceres screamed, "Who's out there?" Before Castro had time to react, a man kicked down his bedroom door and pointed a gun at his face. It was 11:40 P.M. on March 2, 2016.

Castro, a Mexican activist who had spent his life involved in a range of social justice campaigns, was in La Esperanza, Honduras, to coordinate a three-day workshop on creating local alternatives to capitalism. Cáceres—one of the most revered environmental, indigenous, and women's rights leaders in Honduras—had invited Castro to conduct the workshop for members of her organization, the Civic Council of Popular and Indigenous Organizations of Honduras, known by its Spanish acronym, COPINH. When he accepted the invitation to travel to Honduras, Castro knew that it could be dangerous, though he had no idea exactly how grave it would turn out to be.

Bertha Cáceres Zúñiga (daughter of Berta Cáceres) stands next to the Gualcarque River, which her mother died protecting.

In recent years, Honduras had become a global leader on lists having to do with violence: the highest number of homicides per capita, the world's second-most-murderous city (San Pedro Sula), and the most dangerous place on the planet to be an environmental advocate. As the most prominent spokesperson for a fierce indigenous campaign to stop the construction of a hydroelectric dam on the Gualcarque River, Cáceres was no stranger to threats. The struggle over the proposed Agua Zarca dam had become a major political controversy. On one side were the indigenous Lenca people of COPINH, who had staged road blockades, sabotaged construction equipment, and appealed to international lenders to halt financing for the project. On the other were some of Honduras's wealthiest families, many of them with close ties to the military. Cáceres's leadership against the dam had earned her much attention, both positive and negative. In 2015, she received the prestigious Goldman Environmental Prize—and leading up to it, she also had received beatings from security forces and some 30 death threats, and spent a night in jail on fabricated charges.

Castro and Cáceres had been friends for more than 15 years and had collaborated on opposing the Free Trade Area of the Americas, open-pit mining, water privatization, and militarization. Castro's workshop in La Esperanza was focused on developing strategies for moving beyond protest-centered social movements, and Cáceres had been energized by the sessions. That day she left repeated WhatsApp messages for her daughter, Bertha Cáceres Zúñiga, who had just left Honduras to resume her graduate studies in Mexico. "She was really happy," Cáceres Zúñiga said.

After the first day's workshop, Cáceres had invited Castro to spend the night at her home so that he could have a quiet place to work. They arrived sometime around 10:30 P.M. after driving a mile and a half down a lonely dirt road from the center of La Esperanza. Castro remembers commenting on how isolated the property was. "How is it that you live here alone?" he asked Cáceres as they pulled up to the house.

The old friends spent some time talking on the front porch, and then each went to their own room. It was nearing midnight when the gunmen forced their way into the house and he heard Cáceres's screams. "That's when I realized we were dead," Castro said.

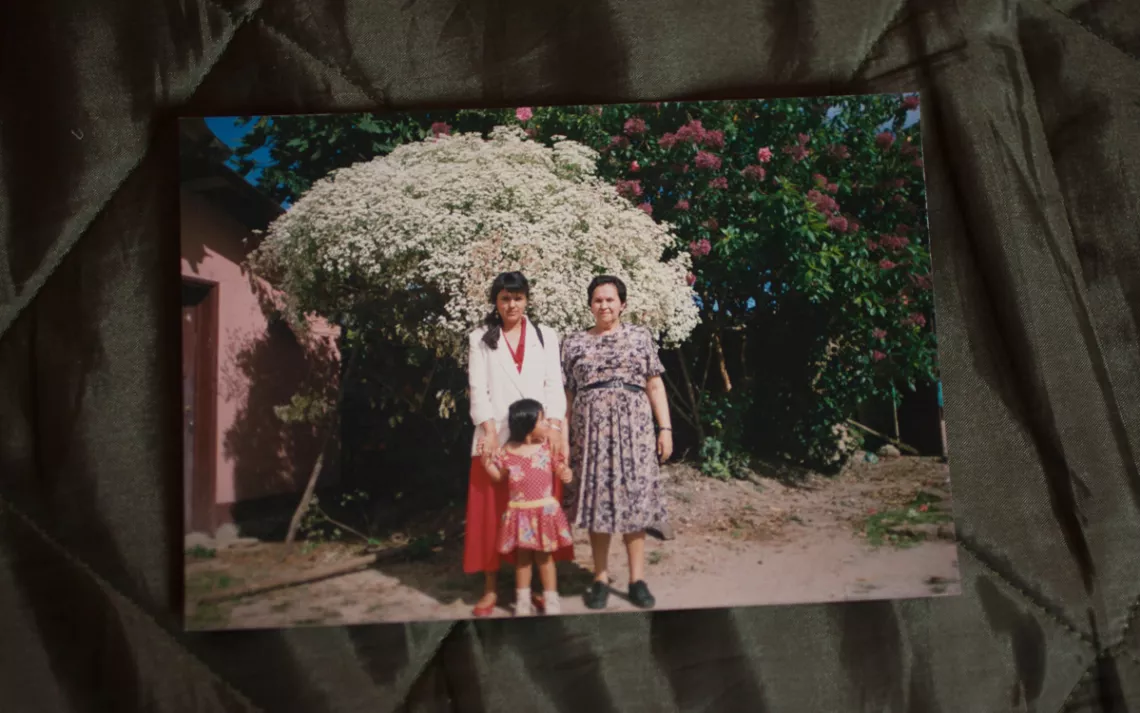

Berta Cáceres's sister and mother

In the instant before a shot was fired at him, Castro looked past the gun barrel and into the gunman's eyes. "When I saw in his eyes the decision to kill me, I instinctively moved my hand and head," Castro told me, showing me the scar on the back of his hand and lifting up his hair to reveal where a bullet had removed the top of his ear. "The killer experienced an optical illusion that he had shot me in the head. Because in the instant that he fired, I was still. But a millionth of a second before, I moved my hand and head. If I had moved a millionth of a second later, we wouldn't be sitting here."

Castro threw himself to the ground and lay still, pretending he was dead. He was bleeding from his ear, which was covered by his thick, curly hair. The gunman turned and walked out of the house.

"A few seconds later," Castro said, "Berta screamed, 'Gustavo! Gustavo!' And I went to her room to help her. But it wasn't more than a minute before Berta died. I said goodbye to her, grabbed the phone, and went back to my room to start calling people so that someone could come and rescue me. It didn't take more than 30 seconds, a minute, from the time the killers entered to when they left. Everything happened so quickly. They were there to kill her. It was a well-planned assassination. The only thing they hadn't anticipated is that I would be there."

It was two days before Cáceres's birthday. She would have turned 45.

IN 2010, THE RESIDENTS OF RÍO BLANCO, a Lenca community on the banks of the Gualcarque River, noticed workers with heavy machinery. They were "making roads where they had no business making roads," said Rosalina Domínguez, a community leader there. The Lenca wasted no time in making their opposition known. "We confiscated one of their tractors," Domínguez recalled. "We didn't let them get much work done."

A few months later, a group of men arrived in Río Blanco to show promotional videos for the hydroelectric dam they wanted to build, and to tell the community about the studies they had already done on the proposed project. People were unimpressed by the gesture. "Who gave you permission to conduct those studies?" they asked. An engineer said that the dam would provide the community with jobs, schools, and scholarships for their children. "We told him that it sounded like a bunch of promises that they would never follow through on," Domínguez said. "So the community told him that we wouldn't accept the project and that if someday they decided to try and build it anyway, the community would stand up and fight."

In 2012, the company behind the proposed Agua Zarca dam, Desarrollos Energéticos (or DESA), sought to buy the land along the riverbanks. According to Dominguez, out of some 800 community members, only seven wanted to sell. A year later, the company moved ahead with construction anyway. In March 2013, a number of indigenous farmers walked out to their corn and bean fields to find they were no longer there. "We decided to fight when we saw how they destroyed the cultivated fields without so much as talking to the owners," Domínguez said. "They plowed straight through the ears of corn and the beanstalks. That is when we blocked the road."

Berta Cáceres's home, outside La Esperanza, Honduras

Two days after the Lenca community set up its road blockade, Berta Cáceres arrived. Domínguez and Cáceres had met in 2009, when Cáceres went to Río Blanco to give a talk about the international laws protecting indigenous communities' rights and to make a case for the importance of protecting the river. When Cáceres returned in April 2013 at the start of the road blockade, "she joined the struggle unequivocally," Domínguez said. "She stayed with us day and night."

United in its determination to halt the dam, the community of Río Blanco possessed a clear moral and legal stature: International law states that indigenous communities must give prior consent for projects like Agua Zarca, consent that the dam builders had not received. Cáceres brought to the conflict a strategic savvy honed during 20 years of social-change organizing. Her life to that point had prepared her for this very struggle.

Berta Flores Cáceres was born in La Esperanza in 1971 to a politically active family. Her mother, Austra Bertha Flores López, worked for decades as a midwife, assisting thousands of natural births in the Honduran countryside. She was also—while working full-time and raising 12 children, of whom Berta was the youngest—three times the mayor of La Esperanza, once the governor of the department of Intibucá, and later a member of Honduras's congress.

Berta took to politics early. At age 12, she ran for student council and began participating in street demonstrations. During political meetings at the family home, she met Salvador Zúñiga the man with whom she would eventually have four children and share more than 20 years of grassroots struggle. When she was 17, the couple had their first child, a daughter, shortly before crossing the border into El Salvador to join the Farabundo Marti National Liberation Front guerrilla army during that country's brutal civil war. Her mother speaks of this with pride: "She went to fight, rifle in hand."

After the war ended, in 1992, Zúñiga and Cáceres returned to Honduras, had their second daughter, Berta, and made a pact to never go to war again. "We understood that war was repugnant," Zúñiga said. "It was the worst thing that could happen to people." They committed themselves to "active nonviolence" and together founded COPINH.

In the subsequent years, Cáceres, Zúñiga, and COPINH would lead major indigenous marches to Tegucigalpa, the capital, and establish two autonomous indigenous municipalities—the first in Honduran history. Using grassroots organizing and lawsuits, they were able to halt the voracious logging in Intibuca. They also founded a women's health center and five indigenous radio stations and established a social-movement training and retreat center on 10 acres of land in La Esperanza. "The whole world admired her," her mother said. "She traveled abroad to help, to give trainings, to give talks, and to carry the message of what was happening here. She had this immense ability to defeat, a little bit, the huge power of the businesses and the big landowners that were her enemy."

When Cáceres arrived in Río Blanco in the spring of 2013 to help stop the proposed Agua Zarca dam, she brought with her not only the skills of a seasoned organizer but also a national profile that was essential to elevating the struggle. As the blockade continued, DESA engineers and security personnel repeatedly threatened Río Blanco community members, though Cáceres soon became the focal point for threats and intimidation. DESA charged that the Lenca people—though they were living in their communities and farming their ancestral lands—were trespassing. On several occasions, the police dismantled the COPINH roadblocks, and each time the community put the blockade back in place. In mid-May, the Honduran government deployed the military. Soldiers from the Battalion of Engineers established a base camp inside DESA's facilities.

The close cooperation between the dam builders and the military was part of a larger relationship. DESA's executives and board of directors come from the Honduran military and banking elite. DESA's secretary, Roberto Pacheco Reyes, is a former justice minister. The company president, Roberto David Castillo Mejia, is a former military intelligence officer accused of corruption by the Honduran government's public auditor's office. The vice president, Jacobo Nicolas Atala Zablah, is a bank owner and a member of one of Honduras's wealthiest families.

Within days of the soldiers' appearance at the site, someone planted a handgun in Cáceres's car. She had already been searched at several police checkpoints when a subsequent military search suddenly revealed a firearm in her vehicle. Cáceres was arrested and taken to jail. She was able to post bail, and the gun charges were dropped, but then DESA filed a lawsuit against her for illegally occupying company land, and the Honduran federal prosecutors added sedition charges for good measure. Fearful of being arrested again, Cáceres went underground as her attorney fought the charges.

"Everything against Berta shows that there is a connection between the military and the company," said Brigitte Gynther, who has been working in Honduras with the School of the Americas Watch since 2012. "It was the military that had Berta arrested. The collusion between the military and DESA has been a constant since the beginning."

Then the standoff turned deadly. On July 15, 2013, COPINH staged a peaceful protest at the dam company's office. The demonstration had barely started when soldiers opened fire on the COPINH activists at close range, killing community leader Tomas Garcia and wounding his 17-year-old son, Alan.

The military's attack on unarmed protesters marked a turning point. In August 2013, the giant Chinese dam-construction company Sinohydro pulled out of the project, citing the ongoing community resistance. The International Finance Corporation, a private-sector arm of the World Bank that had been considering investing in the dam, announced that it would not support the project. With funding in jeopardy, work on the dam limped along.

In the spring of 2015, Cáceres traveled to the United States to receive the Goldman Environmental Prize for her leadership in the dam struggle. Sometimes referred to as the Nobel Prize of the environmental movement, the award recognizes individuals who take great personal risks to protect the environment. In that sense, Cáceres was an ideal recipient. Since the dam conflict had begun, she had received many death threats. At one point, another activist had shown her a military hit list with her name at the top. (The Guardian later published an interview with a former Honduran special forces soldier who confirmed the existence of the hit list.)

Many of Cáceres's friends and colleagues hoped the Goldman Prize would help protect her. "They gave her the Goldman, and I went with her [to the ceremony]," said Melissa Cardoza, a feminist organizer and writer who was a close friend of Cáceres's. "And I thought, OK, she's in the clear. This is going to back her up. Because for a long time she told me, 'They are going to kill me because they won't be able to put up with our winning this struggle.'"

GUSTAVO CASTRO WAS STILL bleeding from his wound when the cellphone of his dead friend rang. It was Karen Spring, a Canadian activist with the Honduras Solidarity Network. Spring was lying in bed around 1 A.M. on March 3, 2016, when she received a voicemail from a friend who said that Cáceres had been murdered and a Mexican activist was stuck in her house, wounded. When Spring called Cáceres's number, Castro answered. "I asked him how badly he was injured," Spring remembered. "He said that he was bleeding from the ear, that there was a lot of blood, but that he was OK." Castro was terrified that the killers would return and was desperate to get out of the house. He asked Spring if he should call the police, and Spring said she would first try to get COPINH members to rescue him. "You can't call the police," Spring told me. "It's like calling the mafia to the crime scene."

From the beginning of the investigation, the police tried to blame the murder on someone from COPINH. They repeatedly interrogated Tomás Gómez Membreño, a veteran COPINH member who was among the first to arrive at the murder scene and help Castro. For two days, they detained Cáceres's onetime boyfriend Aureliano Molina, even though he had not been in La Esperanza on the night of the murder. As detectives interrogated Gustavo Castro to draw a portrait of the man who had shot him, they ignored Castro's descriptions and kept trying to draw a portrait of Molina. "I realized this days later," Castro said, "when I saw his picture in the newspapers and I said to myself, 'That's the man they were trying to draw.'"

The police initially attempted to involve Castro in the murder. They kept him for days without medical attention, interrogating him at the crime scene over and over. After they told him that he was free to return to Mexico, he was nearly arrested at the airport. Fortunately for him, the Mexican ambassador was accompanying him, and she literally wrapped her arms around Castro and declared, "Consular protection," allowing him to leave the airport, though not the country. After yet more interrogation, Castro was finally able to return to Mexico and reunite with his family almost a month later.

Two months after Cáceres's murder, amid massive national and international outcry, Honduran officials began to make arrests. Analyzing phone records, prosecutors sketched an alleged web of complicity involving eight people: an active military officer, Major Mariano Díaz; two DESA employees, an Agua Zarca manager named Sergio Ramón Rodríguez and Douglas Geovanni Bustillo, an ex-military man who was DESA's chief of security between 2013 and 2015; two former soldiers, Edilson Atilio Duarte Meza and Henry Javier Hernández Rodríguez; and three civilians with no known connections to DESA or the army, Emerson Eusebio Duarte Meza (Edilson's brother), Óscar Aroldo Torres Velásquez, and Elvin Heriberto Rápalo Orellana. (According to the Guardian, both Díaz and Geovanni Bustillo received military training in the United States.) Honduran officials charged all eight with murder and attempted murder; all but one of the suspects have denied any involvement with the murder.

The arrests immediately cast a shadow on the Agua Zarca dam. Even after Cáceres's murder, DESA had kept working on the dam. When federal police arrested two DESA employees in connection with the murder, the company halted work. The project remains suspended today. (DESA did not respond to interview requests via email and phone. In statements to the press, the company has repeatedly denied any connection to Cáceres's murder.)

The Cáceres family and members of COPINH pointed out that investigators had failed to apprehend, or investigate, any possible high-level intellectual authors of the murder. "The public prosecutor accused her of being an instigator and of stealing from a company [DESA]. And now that same institution and the same individuals are the ones investigating her murder," said Victor Fernández, COPINH's attorney. "According to the prosecutor's hypothesis, they have arrested the material authors and the intermediaries. But not the main perpetrators."

COPINH and the Cáceres family also complained that the investigation had been compromised by political espionage that appears to have accompanied the police inquiry. The entire case file, for example, was supposedly stolen from the trunk of a judge's car. Cáceres's house was sealed and guarded by police and soldiers for five months after the murder, as the federal prosecutor's office conducted its investigation. But when federal officials finally allowed Cáceres's family back into the property, they realized the house had been broken into while under federal control. Police seals on the home and on Cáceres's possessions inside were broken, and her two computers, three cellphones, and numerous external hard drives and flash drives were missing. "They stole all the information about COPINH that was in the house," Cáceres Zúñiga said, referring to government officials.

The Cáceres family's suspicions about the official investigation are inseparable from the broader atmosphere of distrust that has gripped Honduras since the country's president, Manuel Zelaya, was overthrown in a 2009 military coup. Zelaya had raised the national minimum wage, proposed turning the massive U.S. military base in Honduras into a national airport, and made promises to indigenous and farmer organizations that he would grant their land claims. Such a program ran counter to the interests of Honduras's entrenched elite, which deposed him in the middle of the night and put him on a plane in his pajamas. "The right wing didn't just carry out a coup d'etat; they safeguarded their economic project," Fernández said. "That is, they used the coup to produce a series of legislative reforms and institutional restructuring that gave them control over key areas and the whole process of remilitarizing the country."

Soon after the coup, in 2010, a single act of congress granted 41 concessions for hydroelectric dams on rivers across the country. In April of that year, the Honduran government held an international investment convention called "Honduras Is Open for Business." The country's mining regulations were relaxed, and a moratorium on new mines was repealed. According to human rights groups, illegal logging increased in the wake of the coup. At the same time, threats against, and murders of, activists began to climb.

"Everything that is happening now stems from the coup," Cáceres Zúñiga said. "It was the opening of everything that Honduras is going through now. All the violence, corruption, territorial invasions—that is the coup."

Cáceres was a national leader of the resistance movement against the coup. She took to the streets and to the airwaves. She traveled to El Salvador to participate in a protest outside the building where the Organization of American States was meeting to discuss whether to allow Honduras back into the organization. By the time she took the helm of the struggle against the Agua Zarca dam, the coup government had identified her as an adversary. It was in this context that she became the target of a vicious smear campaign apparently orchestrated by DESA and Honduran officials. "There was this constant defamation campaign, especially for her as a woman. She was painted as this vicious, horrible person," said Gynther, of the School of the Americas Watch.

Of the eight people currently under arrest and awaiting trial, only one, Hernández Rodríguez, has given detailed testimony that is admissible in court. Hernández Rodríguez was arrested in January 2017 while working at a barbershop in Reynosa, Mexico, and extradited to Honduras. He had been a Honduran special forces sniper with the rank of sergeant stationed in the Lower Aguán Valley and had served directly under Major Díaz. After he left the military, he went to work as a private security supervisor for a palm oil corporation, Dinant, also in the Lower Aguán (see "No One Investigates Anything Here").

I was able to gain access to an audio recording of Hernández Rodríguez's testimony. His description of the mechanics of the murder coincides with the physical evidence in Cáceres's house and with Castro's eyewitness testimony. While Hernández Rodríguez says that he cooperated with the assassination only under duress and that he didn't carry a gun the night of the murder, his confession offers some new details. According to Hernández Rodríguez, the murder was planned well in advance: He and Geovanni Bustillo visited La Esperanza in late January and early February. Hernández Rodríguez admits to experience in this kind of political violence: Police have cellphone recordings of him bragging about committing a previous murder and discussing with Díaz what appear to be the logistics for the assassination of Cáceres. And he confirms, using their nicknames, the identities of the men who entered Cáceres's house and shot Berta and Gustavo: Rápalo Orellana and Torres Velásquez.

Yet all of the physical evidence and testimony still do not answer the question of who, exactly, ordered the assassination. When asked this question by investigators, Hernández Rodriguez responded, "They only said that it was a job that had begun and that it had to be finished. That's all they said."

The long-running campaign against Cáceres—plus the alleged involvement of active and former military officers and DESA employees in the coordination and carrying out of the murder—has fueled suspicions that her murder was ordered by people highly placed in the Honduran government, military, and economic elite. (Honduran officials have denied any state connection to the murder.) But, according to COPINH members and Cáceres's family, police have not sought to establish who was behind the assassination.

The question facing Honduran social movements and the Honduran government is, Will those responsible get away with murder?

A YEAR AFTER HER ASSASSINATION, I went to Cáceres's home with her daughter. The small green house is surrounded by empty fields and a few other new houses and has beautiful views of the nearby mountains. Cáceres had only recently finished making payments on the home, with funds from the Goldman Prize, when she was killed. At the spot where her mother died, Cáceres Zúñiga maintains a thick circle of cypress and guava leaves from her grandmother's backyard, arranged around a candle on the floor.

As Cáceres Zúñiga walked me through the property, explaining her understanding of what happened the night of the murder, she expressed frustration at how her mother has been remembered since the assassination. Too often, she scoffed, Berta Cáceres is reduced to being just an "environmentalist" or "Goldman Prize winner," when in fact she was much more than that. I heard similar complaints from everyone who knew and loved Cáceres.

"It really hurts me when they only call her an environmentalist," Miriam Miranda told me. "Berta was a feminist, indigenous woman of struggle who definitely fought for natural resources, but she was profoundly feminist." Miranda is the leader of the Black Fraternal Organization of Honduras, and over the course of 25 years of shared struggle, she and Cáceres developed a deep friendship. She has survived beatings and assassination attempts and, since Cáceres's murder, has become probably the highest-profile social-movement leader in Honduras. "They ripped out a part of my life," Miranda said. "[Berta] was always there with me in the hardest moments of my life."

During the demonstrations and vigils marking the first anniversary of her murder, I heard the following chant over and over: "Berta did not die. She became millions!" In the wake of political murder, one task of survivors is to refuse the logic of killing: the fear, hopelessness, and paralysis. To honor the fallen and what they offered, one must not only continue the struggle but fight harder and become one of the millions in whom those like Cáceres live on.

"Her life's work was insurrection," said Melissa Cardoza, the feminist organizer and writer. "One day I was with her when she was being arrested. The police were taking down her information, and I was with her. And the cop asked her, 'What is your profession?' And she said, 'I'm a professional agitator.' The cop said, 'I can't put that down.' And she asked why not? 'Because it doesn't exist,' the cop said. And so she turns to me and says, 'You tell them. I'm a professional agitator.' And so I told the cop, 'Well, it's true. That's what she does.'

"That was our Bertita."

This article appeared in the July/August 2017 edition with the headline "Under the Gun."

Read about the Afro-Honduran Garifuna people's struggles to defend their lands in the face of intense violence: sc.org/garifuna.

Watch a video about the Garifuna way of life: sc.org/glife.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club