First Nations Women in Canada Are Suffering From an Epidemic of Violence. Why?

Resource extraction exacerbates the problem

Photography by Hope Linzee

CONNIE GREYEYES WAS 16 when her first friend went missing. It was 1988, and Stacey Rogers was a year older than her. They were friends from the pool hall where high school kids in Fort St. John—a timber, oil, and gas town in rural northeast British Columbia—would hang out. Greyeyes remembers Stacey as tough, outspoken, and fun. At the time, she thought maybe Stacey had run away. "I guess my brain didn't want to think that something terrible happened to her," Greyeyes says.

Five years later, Greyeyes's older cousin from Alberta, Joyce Marie Cardinal, was brutally murdered. A stranger beat her, doused her in gasoline, and set her on fire in an Edmonton public park. Firefighters arrived at the scene to put out what they thought was a burning pile of trash.

"Who the hell would do something like this?" Greyeyes remembers thinking.

It's a question she and others in her community have asked again and again. Since Stacey Rogers's disappearance, at least a dozen indigenous women from Fort St. John and surrounding First Nations communities have gone missing or been murdered. Some of their bodies were found and their killers prosecuted. Other cases have gone cold. Ramona Shular went missing from town in 2003. Shirley Cletheroe disappeared three years later after going to a barbecue across the street from her home. Abigail Andrews was last seen in 2010, leaving her house on foot.

Connie Greyeyes in front of Peace River

Violence against indigenous women is not unique to Fort St. John. Indigenous women in Canada are three times as likely as other women to report having suffered domestic abuse and two and a half times more likely to report being victims of violent crime, including physical and sexual assault.

But the problem is particularly severe in and around this small town. A recent research project conducted by the Fort St. John Women's Resource Society found that the local criminal court handled about as many domestic violence cases between 2011 and 2012 as the court in Prince George, a city nearly three times larger. In a community survey that was a component of that research, 93 percent of indigenous women reported having experienced violence or abuse at some point in their lives.

The violence comes both from within indigenous communities and from outside. It is one of the legacies of colonization. Researchers believe there is a connection between the modern-day violence and traumatic experiences like what today's elders endured in Canada's residential schools, the last of which closed in 1996. First Nations children were sent to these schools as part of a policy of "aggressive assimilation" and often were subjected to physical, sexual, and verbal abuse. They brought the trauma they suffered home with them, and it percolated into the lives of their children and grandchildren, contributing to high rates of substance abuse and mental health issues—factors that can lead to violence against women.

In Fort St. John, rampant development of the natural resources—coal, oil, gas, timber, and water—and the social and economic dynamics associated with it add another layer of risk. Development even causes its own kind of trauma by transforming the land base that is central to First Nations culture.

Violence is so common in Fort St. John, Greyeyes says, that it's become normalized. Only recently have she and others started calling it what it is: an epidemic that needs to stop.

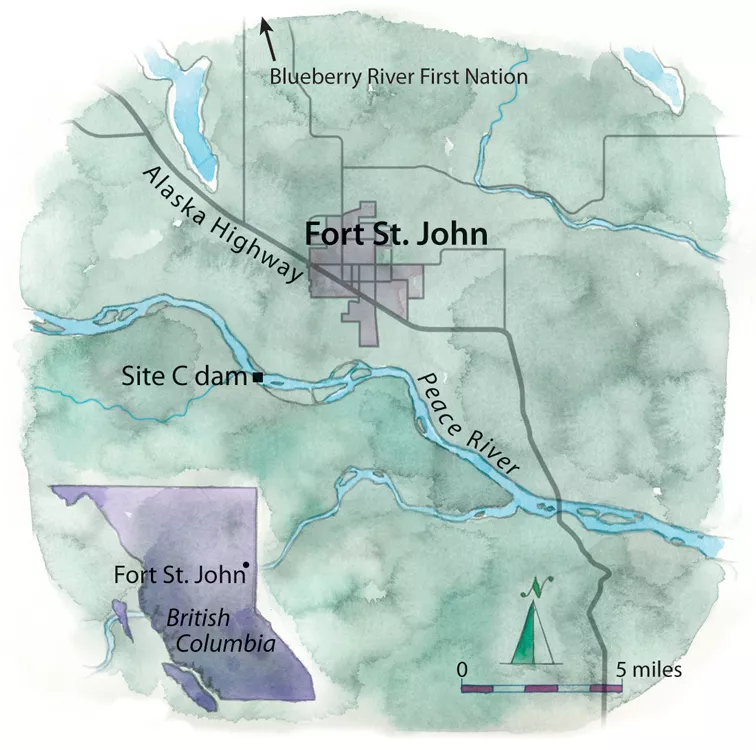

FORT ST. JOHN SITS ALONG the wide, braided Peace River at mile 47 of the Alaska Highway, which connects the U.S. Lower 48 with Alaska. The town is urban by northern standards, with a Walmart and two Tim Hortons, though it and its satellite towns and First Nations villages are home to only around 60,000 permanent residents. Dozens of industrial yards edge Fort St. John, scattered with steel pipe, trailers, storage tanks, and other oilfield implements. Suburban bungalows with grass lawns and two-car garages line wide residential streets, a four-door pickup in nearly every driveway.

Here, North America's Great Plains turn to timberlands and rise and roll toward the sharp, snowy peaks of the Rockies. For tens of thousands of years, the area has been the traditional territory of the Dane-zaa people, whose descendants, along with the Cree, make up many of the First Nations around Fort St. John today.

When the Scottish fur trapper Alexander Mackenzie arrived in the Peace in 1793, he wrote that the prairies were "so crowded with animals as to have the appearance, in some places, of a stall-yard." The Dane-zaa migrated with the seasons, hunting bison, caribou, beavers, and moose. Bands gathered in one spot every summer to reconnect, sing, and tell stories. They called it the place "where happiness dwells."

Today, wildlife populations have dwindled. Clearcuts checkerboard the spruce forests where the Dane-zaa used to make camps and pick medicine. Coal companies have scraped away caribou habitat. The W.A.C. Bennett Dam on the Peace River blocked caribou migration across the river and forced two First Nations off their land. It and a second dam generate 28 percent of British Columbia's hydropower,and a controversial third dam called Site C is slated for completion in 2024. Fort St. John also sits at the heart of the Montney Basin, one of North America's largest shale gas plays. Its recent booms have fragmented the bush with well pads, roads, and pipelines. The Blueberry River First Nation has been particularly affected. Over 80 percent of its traditional territory is now within 500 meters of industrial activity, whether it's a clearcut, a pipeline, or a gas well. Band members call their reserve "Little Kuwait."

A gas station in Fort St. John

One of Fort St. John's most outspoken women's advocates, Greyeyes says it's no coincidence that this is the backdrop against which women experience extraordinary levels of violence. But it took her a long time to see it, partly because violence was ever present in her own life.

Greyeyes is a member of the Bigstone Cree First Nation in northern Alberta but has lived in Fort St. John most of her life. She's married, with two sons, and has a small stake in a local business that insulates pipes in the oil and gas fields. She's brash and outgoing, with freckles on her cheekbones and dark hair parted down the middle.

She grew up as one of 12 siblings on a double lot in the middle of town. She had a loving home, but her parents worked long hours, her dad as a logger and her mom as a dishwasher. Friends and neighbors pitched in with the kids, and one neighbor sometimes took her camping. On these trips, he molested Connie.

"That was my first memory of being abused," she says. "I don't remember how many times they had taken us camping. But I know that the nights were spent trying to keep yourself safe."

The violence took many forms. In the ninth grade, she went to a party and decided to stay when her friends left. She was gang-raped that night. After that, "every weekend was a repeat of the one before," she recalls. "A lot of physical altercations, violence, drugs. When you're in that horrible cycle, you don't even realize your own behavior in it. There were many times I knew I shouldn't stay in a situation and I did."

One night, in her early 20s, she and some girlfriends were out drinking at a local bar called Looney Tunes when a group of oil workers asked them to go somewhere else to party. Greyeyes and her friends said no, but the men kept pressuring one of her friends to go along. "I was like, 'No,' and one of them hit me." Greyeyes ended up with 14 stitches in her lip.

In her mid-30s, after the sudden death of her brother-in-law, Greyeyes decided to stop drinking and using drugs. She went into treatment and for the first time began to talk about being assaulted. Acknowledging what had happened helped release her from it. "I found my voice again," she says. And she found purpose helping other women find theirs.

Connie Greyeyes and others attend a vigil in Ottawa in 2015, honoring victims and calling attention to the epidemic of violence against indigenous women.

EACH OCTOBER, COMMUNITIES ACROSS CANADA hold vigils to raise awareness about the alarming number of indigenous women who go missing or whose lives meet violent ends. In 2008, Connie and a friend organized the first one of its kind in Fort St. John. Since then, she has also traveled regularly to Ottawa, where she has spoken on Parliament Hill about her hometown's missing and murdered women.

In 2014, she made a banner to take along. It listed the names of a dozen victims from Fort St. John, and she affixed photos of six women to it with Scotch tape. The banner caught the attention of Jackie Hansen, a women's rights campaigner with Amnesty International. She was surprised by the number of names, given the area's small population, and asked Greyeyes and a couple of other women from Fort St. John to coffee. "What's going on there?" she asked.

Greyeyes and the other women told a familiar story about racism and the general disrespect shown to indigenous people. They also talked about rapid environmental changes, fast money, rising housing costs, the transient workforce, and a hard-partying, macho culture. They talked about the fight over the Site C dam, which would bring more out-of-town workers.

Following that conversation, Greyeyes invited Hansen and a small team from Amnesty to conduct a research project in Fort St. John. Their report was released last fall and is based on more than 100 interviews, a literature review, and public data. It concludes that the social and economic dynamics that accompany resource development heighten the risk factors for violence against women, during both boom times and busts.

Though oil companies have explored the Peace region for petroleum since the 1950s, activity skyrocketed in the early 2000s as new drilling techniques opened up the Montney Basin's vast shale gas reserves. Money and workers poured into Fort St. John. By the end of 2014, unemployment was so low in northeast British Columbia that the national statistics agency considered it unreportable.

But by spring of 2015, the gas boom was starting to bust thanks to a supply glut, which drove prices down. By June, unemployment had reached 5.9 percent. And by the end of 2016, it had nearly doubled, to 10.5 percent.

Map by Steve Stankiewicz

The turbulent economy and the ebb and flow of workershave caused an affordable-housing crisis. Fort St. John's housing costs are the highest in northern British Columbia.In 2014, the average selling price of a home was $414,646. Women earn significantly less money than men here—$34,958 a year, on average, compared with $63,658 for men. That gap is almost double the national average. Not infrequently, women have to choose between leaving an abusive partner and becoming homeless, says Sylvia Lane, a poverty law advocate at Fort St. John's Women's Resource Centre and a contributor to the Amnesty report.

The report also highlights how the culture of the remote industrial camps contributes to violence against women. The working conditions can deteriorate the well-being of workers, who are mostly male and spend three weeks to a month in camp pulling 12-plus-hour shifts. The work pays well but can be stressful and dangerous, and the time away from home strains relationships. In the camps themselves, drug and alcohol abuse is common, and workers have little access to physical and mental health services.

All of this can put women at risk. "How hard you work, how much you party, and how many toys you have—that's oil-patch culture," one woman, whose partner works in the industry, told Amnesty. "I don't get hit, though I get a lot of emotional abuse. But some women get hit because their men hit the bar first. They come home, they come through the door, and they explode."

The average number of clients the Women's Resource Centre—the town's only social service center dedicated to women—serves per month rose by 65 percent in 2016 amid the bust. By March 2017, it had risen by another 20 percent. Yet the center is constantly scrambling for funding. In 2006, Stephen Harper's conservative government cut federal funding for women's centers like Fort St. John's. Amanda Trotter, the center's executive director, says they were able to stay open largely due to charitable grants and donations from businesses in the community. During busts, though, when need is highest, local donations dry up.

A big problem, Trotter says, is that at the levels of government where the decisions are made to green-light pipelines or projects like the Site C dam, there's no comprehensive planning for community-level social effects. Instead, decisions are made on a project-by-project basis, and the government review process doesn't require any gender-based analysis, meaning that impacts specific to women aren't accounted for in the planning process. "I would like to see some overall plan," Trotter says. "What is the impact of not each project individually, but cumulatively, on the land and the people?"

In June of last year, two First Nations in central B.C. that will be affected by the construction of a major pipeline held a workshop with industry and government representatives to identify strategies for mitigating problems caused by construction camps. The ideas they came up with includedkeeping workers' vehicles more than a kilometer from camps, which has been shown to decrease substance use and prostitution, says Ginger Gibson of the Firelight Group, which provides research and technical assistance to the First Nations. Community events that include both workers and locals can also help forge positive relationships, she says, "so that everybody in the camp thinks of the people in the region as people they should treat with respect and kindness, because they play ball with them or whatever."

For some communities, though, finding better ways to accommodate new development isn't answer enough.

NORMA PYLE COMMUTES DAILY FROM Fort St. John to the Blueberry River First Nation's reserve, about 3,000 acres on the banks of the Blueberry River, an hour north of Fort St. John. Pyle, who has short, neat gray hair and a no-nonsense manner, is the reserve's lands manager.

To get to work, Pyle drives the Alaska Highway north before turning east into what just a few decades ago was still rugged bush. Now it's a fragmented landscape—a patchwork of farms, clearcuts, forested islands, well pads, pipelines, and waste facilities. The government is required to consult Pyle's band—or at least notify them—before it approves projects in their traditional territory, but most of the time, she says, projects go forward even when they object. And though the band isn't against development, per se, Pyle says the cumulative impact of resource extraction has proved disastrous for their culture.

Pyle's mother describes the era before the Alaska Highway was built in 1948 as a time "when the world was free." They could live anywhere, trap anywhere, hunt anywhere. "Don't get me wrong, it was hard living," Pyle says. "But it was good at the same time. There was always good water. There was a lot of game."

For a time, Pyle says, many members of the reserve made a living trapping beavers and selling their pelts, which allowed them to carry on a traditional lifestyle. "People used to go out every summer and camp and live off the land. The mid-'80s was probably the last time people really did that."

In the 1990s, oil and gas activity started to pick up. The development delivered monetary wealth to the band in the form of jobs that pay better than trapping or royalties from drilling. But it also extracted a social toll. Pyle says drug and alcohol abuse increased markedly with the influx of money and the abandonment of dependence on wildlife for sustenance.

"Our traditions are on the brink of being lost," Pyle says. Both practical skills and cultural knowledge used to be passed between generations on the land. Boys and girls were taught to hunt, to prepare moose hides, to smoke meat over green poplar, to locate medicinal plants. "There's a small contingent of people who have that very limited knowledge that could still transfer it to younger generations," Pyle says. "But where do you go?" Each year, it gets harder to find places in the bush that aren't influenced by pipelines, or heavy-haul traffic, or ranging cattle.

"It used to be the pressure on the family was to survive, and they did it as a unit, collectively," Pyle says. "The familyunit has changed, and it has a lot to do with being displaced off the land. Our men can't be men anymore, and our womencan't be women."

Georgina Yahey, who works with Pyle in the lands office, says she doesn't always feel safe in her own community anymore. She locks her doors at night. She's seen unfamiliar men driving through the reserve, talking to young girls. Three years ago, one of her best friends, Pam Napoleon, disappeared from the reserve. Her bones were found weeks later in a cabin that had burned to the ground. The police deemed her death suspicious but have yet to solve the case.

"It's loss, I guess," Yahey says about the changes in the land and the social disruption within her community. In her eyes, colonization hasn't ended. "On the weekends, I take my mom out, and some of the elders. There's such silence in the vehicle. They're so devastated driving by a clearcut where they once lived. They ask me over and over, 'Why are you guys not stopping them?'"

BESIDES SERVING ON THE BOARD of the Women's Resource Centre, advocating for families of victims, facilitating the Amnesty research, and organizing vigils and informal local support groups for women who have experienced violence, Greyeyes has been active in the fight against the Site C dam. The dam is already under construction, but she and other local opponents are hopeful that the recent provincial elections might yet turn the tide.

Greyeyes is worried that the strain on social services and the influx of transient workers will lead to yet more violence. But she also sees the dam as a symbol of how the casual disregard for indigenous rights persists in Canada. "It doesn't take a genius to figure out that years of oppression toward our people, the injustices that are quite blatant, have given this misconception to Canada regarding its first peoples," she says. "It doesn't take a genius to figure out that it's OK to treat indigenous people this way. They've given you a free pass. To me, that's how it feels."

This article appeared in the September/October 2017 edition with the headline "The Place Where Happiness Dwelled."

Read about how the Site C mega-dam threatens British Columbia's Peace River: sc.org/sitec.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club