Military Moms Find Camaraderie, and Peace, in the Outdoors

Adventure therapy can help veteran mothers transition to civilian life

Harlem, daughter of navy veteran Moet Valdez, takes the lead during a hike in New York's Harriman State Park. | Photos by Robyn Twomey

SHERRY SWARTWOUT HAD NEVER MET a fellow military veteran who was also a single mother until last June, when, on a warm Friday night, she found herself sitting at a campfire with four others. It was 2 A.M., and the women had been talking and stoking the fire for hours. All their kids had long since zipped into tents, surrendering to s'mores and sleep.

"'Are you a single mom? Are you a veteran? Do you want to go camping?' It was just way too specific," Swartwout, a 29-year-old master's candidate in mechanical engineering at Manhattan College and a former navy sonar tech, told the group.

Moet and Harlem Valdez at their Newburgh, New York, home

She was referring to the email she'd received from the Sierra Club's Military Outdoors program. Recruiters for the program had been scouting for potential campers like Swartwout largely through referrals from counselors at the Department of Veterans Affairs in New York City. After googling the Club to make sure it wasn't "some cult," Swartwout responded yes—which is how she ended up 25 minutes north of the Bronx camping for the first time, at a lakeside site in New York's placid Harriman State Park.

Moet Valdez, a fast-talking 27-year-old navy vet, had largely disconnected from the veteran community since being discharged in 2013, two years after her daughter, Harlem, was born. When she left the navy, she just wanted to be "normal." Staring into the embers, Valdez said, "Now I'm starting to realize I need vets. I just want to have normal conversations about the military without explanations."

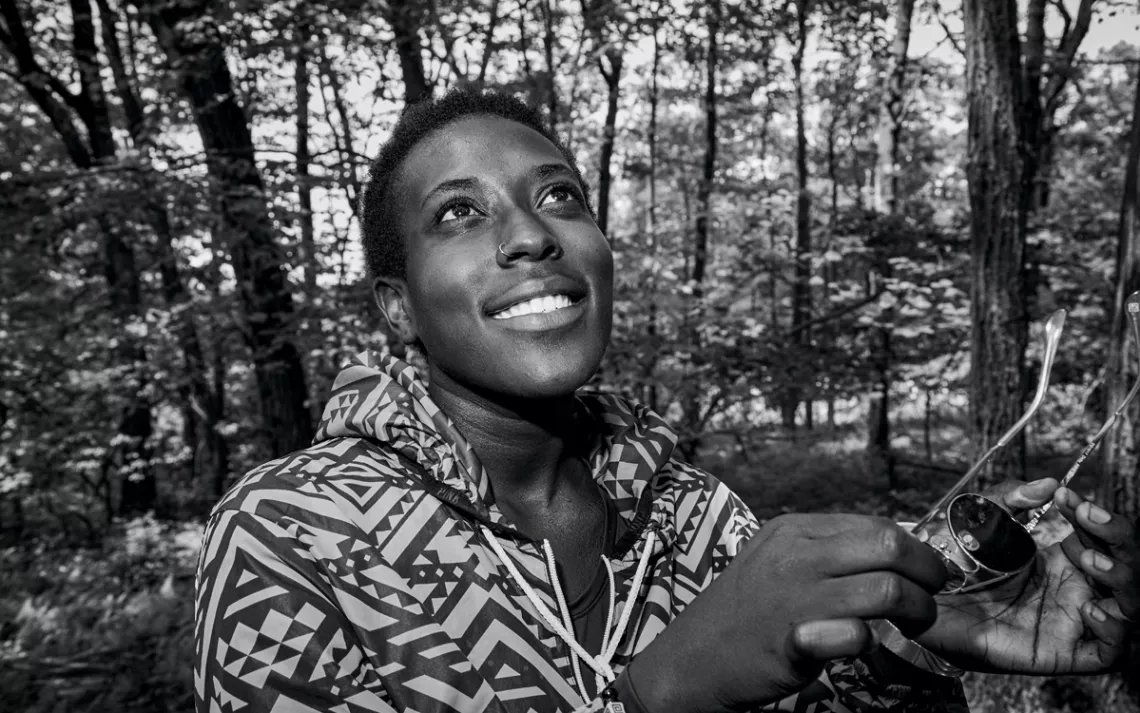

Hawoly Diop

A chorus of yeahs erupted from the circle.

"When you go on a trip like this to the woods," she said, "you get to see your kids, but you also get to realize, I'm not crazy. There are other moms who do this, and we all make it through—but we all suffer sometimes."

This group of five mothers—Hawoly Diop, Ana Karina Perez, Charmaine Denise, Swartwout, and Valdez—would have come off as old friends to any random passerby. But aside from Valdez and Diop, who had briefly been stationed together in San Diego, they were strangers. Some had come with their kids; Valdez's mom, Julissa, was also tagging along to camp with her daughter and granddaughter despite having received chemotherapy the day they left.

They had come to Harriman State Park for a weekend-long trip to connect with the great outdoors, and with one another.

THE MILITARY OUTDOORS single mothers' program draws on the Outward Bound model but with a twist: Camping trips are open to participants' kids and support networks to help eliminate the biggest barrier to getting this population adventuring.

Neither the U.S. Department of Defense nor the Department of Veterans Affairs knows how many single mothers have served in the military. According to demographics from the U.S. Census Bureau, about 120,000 of the 700,000 women who've become veterans since 9/11 are likely to be single and to have children under 17.

Sherry Swartwout with her son, Elijah, outside their home in Inwood, New York

Until the 1970s, women were rarely allowed to serve except as nurses or support staff. Not until 2016 could they assume frontline combat roles in all infantry units. Today, women represent about 9 percent of the military. And still, it's not uncommon for a VA hospital to lack a women's clinic or any female-oriented peer support networks.

Diop is a 28-year-old Brooklyn-based navy vet with a four-year-old son. During a group hike along one of Harriman's oak-shaded, goldenrod-lined trails, she noted that for her, seeking help on a military base—where she served as a communications electrician—amounted to a joke. "You don't want to be the person leaving work to go to therapy all the time," she said during a group water break beside a gentle stream. "You end up considered not deployable. They make it really taboo; it's annoying."

Denise nodded. "When I was handed down orders to become a drill sergeant, do you think I was gonna tell them, 'Oh wait! I suffer from depression and anxiety'?"

A self-described "isolator" dealing with post-traumatic stress, Denise, 48, served in the army for 15 years and, before this outing, hadn't voluntarily left her home in the Bronx for weeks. She adores hiking, though, and couldn't resist a trip to the woods. Her struggles, she told Diop, only intensified once she left the army—where she was a personnel management specialist—to be more present for her son, now 24 and living in Hollywood. After Denise's brother drowned in 2015, the VA prescribed her a medication that made her sleep for three days and later had her sleepwalking.

Moet and Harlem atop a fire tower

"I don't really have a relationship with my family—it was always just me and my son—so when you're out there by yourself, and for all you know, people might not care whether you're alive . . . well, it's something."

ALONG THE STEEP TRAIL to Harriman's fire tower—a lonesome steel structure atop a boulder overlooking rolling hills and, beyond them, New York City's smudged skyline—Valdez joined the conversation. When she left the navy, the VA prescribed Trazodone for depression, anxiety, and adjustment disorder—something she'd still like to see defined.

"I'd just spent nine months away from my child; I'd just gotten out of the military," she said. "The life structure from my past five years was gone. But I felt like I just got labeled and shoved into a corner."

Two hours after setting out, the group reached the tower. Everyone high-fived. After the kids played a game of tag, their mothers hustled them away from the tower's rickety stairs, except for Valdez, who climbed as high as possible with her daughter.

They quietly gazed toward the city.

Sherry and Elijah share water on the trail.

"I like it here in the wilderness," Valdez finally said, taking in the view of treetops tapering toward the fuzzy edges of skyscrapers and bridges. "Look at us: We're away from all the social norms and societal distractions."

It was crucial that everyone—from Ryan, the youngest camper at three, to Julissa—make it to the fire tower. It was also important that the veterans and their families figure out how to cook over the open fire together, to set up their tents together.

That's what they'd come to do.

AARON LEONARD, AN ARMY COMBAT VET who now serves as the veteran outdoor representative for Sierra Club Military Outdoors, says there's a process a person goes through when she endures physical and mental challenges around others with whom she shares a formative life experience. "You build trust," he says, "and everyone comes out of the experience feeling better not only about themselves but also about that group."

On a beach overlooking a lake in Harriman State Park, the children play while their moms do what they came here to do: connect.

The approach, known as therapeutic adventure, has its roots in the military. Outward Bound, the first modern wilderness-immersion program, was created to boost soldiers' resilience at sea during World War II, when ships were being torpedoed crossing the Atlantic.

Still, it's hard to get city-based single mothers adventuring outdoors. Aside from Valdez, who liked sleeping on the beach on off-duty nights when she was stationed at Naval Base San Diego, and Diop, who camped in the California desert during her assignment at the naval base, no one on the Harriman trip had camped before.

Swartwout, who's raising her precocious five-year-old son, Elijah, in the Manhattan public housing apartment that she grew up in, had wanted to camp for as long as she could remember. "I want my kid to grow up getting dirty and seeing raccoons." That had been impossible without a car, gear, anyone to adventure with, or any camping experience.

The Harriman weekend was part of an attempt to redress what Leonard describes as the "gap in services" for single-mother vets. The first step? Recruit cohorts from specific regions (which is why all the campers lived in or near New York City). That way, they can continue to build community once the guided adventure is over and everyone has gone home.

The leaders who facilitated the camping trip invited everyone to join a geocaching scavenger hunt in Central Park the following weekend. The group now kayaks together too. And the circle has grown—in August, more than a dozen single mothers and their kids got together at a lodge in the Adirondacks. Eventually, at a multiday retreat in Vermont, the mothers made their way through a psycho-education workbook about coping with post-traumatic stress, conquering loneliness, and honing parenting skills.

IN THE WOODS, FRIENDSHIP ACCELERATES. Camaraderie is as natural as one's surroundings. Everyone works collectively to protect dinner from sneaky critters, to keep the kids away from ticks and poison ivy.

On the final night in Harriman, everyone stood in a circle as the fire grew and dusk fell. Diop squeezed Denise's hand and said, "You're still on this process that so many of us are on, but because of people who've come before us such as yourself, we know we've got help tackling this."

Swartwout shared that she really misses the navy. She cut her contract short after she had Elijah and her marriage to his father crumbled. She didn't have anyone to look after her infant once her six-week maternity leave was up. Adjusting to civilian life has been hard. It's been difficult to make connections, and her navy friends are far away and growing apart.

"But today," she told the group, "I finally felt that same camaraderie that I felt when I was in the military."

This article appeared in the November/December 2018 edition with the headline "Esprit de Corps." Click here to check out an extended photo essay featuring additional scenes from this camping trip.

This article was funded by the Sierra Club's Military Outdoors program (sc.org/military-outdoors).

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club