The Endangered Species Act Is Still America's Most Radical Law

A portrait gallery of creatures we've saved from extinction

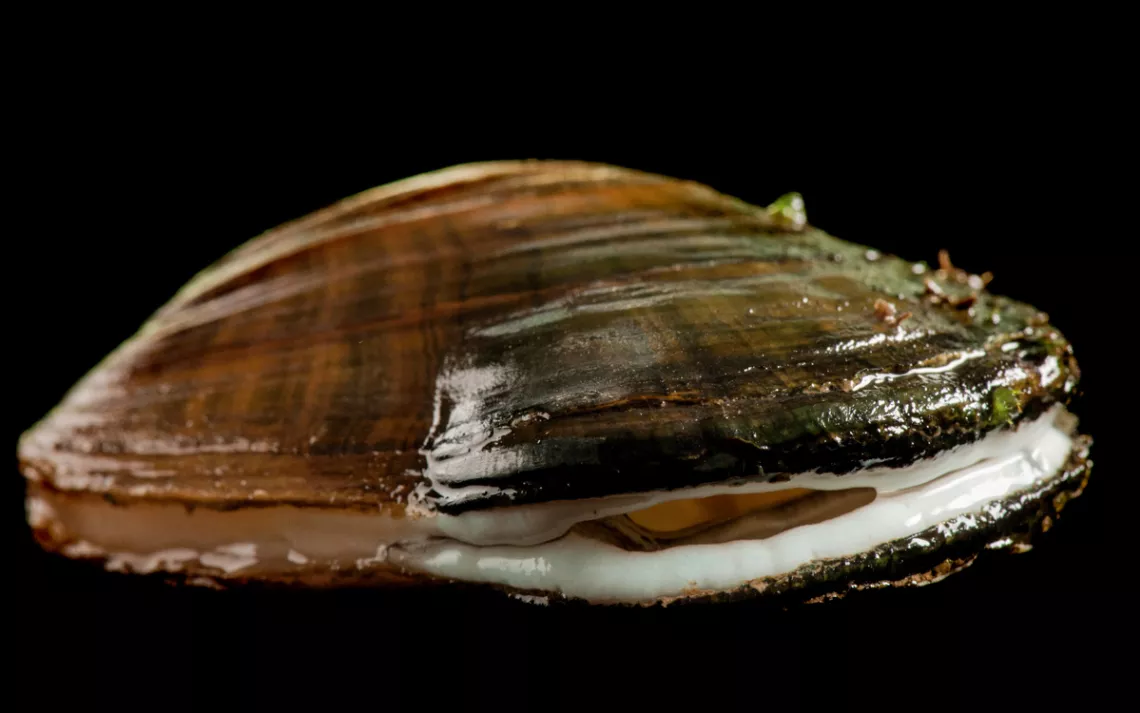

Photos by Joel Sartore

I recently visited the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York City to see an exhibition by David Wojnarowicz, an artist and activist who was just a few years older than me when he died of AIDS-related complications in 1992. One image in particular caught my eye. Titled What Is This Little Guy's Job in the World, it shows a baby toad cradled in a human hand. Legs confidently outstretched, the tiny amphibian seems blissfully unaware that its future depends entirely on human whim. Is the hand moving him out of harm's way, or is it about to snuff him out of existence? If the latter, Wojnarowicz wonders in his caption, "Does the world know? Does the world feel this? Does something get displaced?"

Gazing at that little, uncomprehending toad, suddenly I was no longer standing in an art gallery but had traveled 25 years back and 1,000 miles south, to the swampy patch of woods across from my childhood home in Mississippi, where the humid air hung heavy beneath the pines and life was everywhere. Toads made their home in those woods; also box turtles, jumping spiders, painted lady butterflies, daddy longlegs, green tree frogs, anoles, hognose snakes, mockingbirds, opossums, raccoons, and foxes. As a kid, I marveled at their being, which struck me as just as vital and individual as my own.

This teeming woodland was never supposed to be developed; the owner said so throughout her life and enshrined that wish in her will. But after her death, her children sold the plot. I remember my anguish as the bulldozers moved in.

That same leaden feeling came back when, on a trip to Kenya in 2016, I laid my hand on the craggy, gently heaving back of Sudan, the world's last male northern white rhino. Sudan died in March 2018, and when I wrote his obituary for The New York Times, I couldn't shake the image of him placidly munching some hay, just being a rhino on a drizzly spring afternoon, oblivious to his subspecies' plight. How many more species will be erased in my lifetime?

Our modern natural world is a house of cards in which every species plays a supporting role. With each loss, no matter how big or small, something fundamental and unknowable shifts. Displace enough parts and the whole thing comes crashing down.

In October, the World Wildlife Fund announced that the populations of thousands of vertebrate species around the world have declined by an average of 60 percent since 1970. Plants and animals are disappearing at rates comparable to past mass extinctions—only this time those losses are driven not by asteroids or supervolcanoes but by us, fellow creatures inhabiting this planet. And things are likely to worsen as climate change cranks up and wreaks havoc on delicately balanced ecosystems.

IT DOESN'T HAVE TO BE THIS WAY. Humans are capable of rising above our worst urges to dominate and exploit nature, to instead cherish and protect it. We know that we can, because in 1973 the US Congress came together in bipartisan agreement to pass the Endangered Species Act, which made preventing extinction a moral and legal imperative. Forty-five years later, the ESA remains the best and most effective law for wildlife conservation in the world.

The power of the ESA is that it safeguards not only the 1,618 domestic species currently listed but also their habitats. And not just the big and beautiful: For every whooping crane, red wolf, and grizzly bear listed, there are many oyster mussels, Wyoming toads, and St. Andrew beach mice. The law has also been a huge success—less than 1 percent of listed species have gone extinct, and the act's landscape-level preservation has bettered conditions for countless other creatures.

But conservation is a job that never ends. Every victory can be undone, every success turned into a failure. From the moment of its inception, the ESA has been under attack, most notably from the mining, oil and gas, and livestock industries. The Center for Biological Diversity counts 378 bills that have sought to dismantle critical aspects of the ESA since 1996. And since 2011, when Republicans took control of Congress, those attacks have greatly increased.

Americans do not want this. Since the 1990s, polls have consistently found 80 to 90 percent public approval for the ESA, regardless of political affiliation. Mississippi is as red as it gets, yet Gulf Coast residents delight in the sight of multitudes of brown pelicans—once seemingly condemned to extinction because of DDT—perched on piers or gliding lazily above the gulf's muddy waters. Bald eagles—also once on the brink of extinction—nest on the Back Bay of Biloxi, and critically endangered sandhill cranes swoop majestically over farmland in Jackson County, bound for the nearby federal reserve created for their protection, one of the last remaining wet pine savanna ecosystems in the United States.

While the change in power in the House after the 2018 election lessens the threat, it does not make the ESA impervious to attack. Just weeks after the election, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of Louisiana landowners who sought to develop a 1,500-acre tract designated as critical habitat for dusky gopher frogs, one of the world's most endangered amphibians. The case was sent back to a lower court, and its outcome may affect future critical habitat designations, including one proposed for jaguars in New Mexico and Arizona.

Was the ESA just a blip, a fleeting moment of enlightenment in a world trending toward ecological collapse and the extinction of all but the hardiest generalist species? It's easy to find evidence for that sour view—in Brazil's threat to open the Amazon rainforest to development, for example, or China's flirtation with legalizing the trade in tiger bone and rhino horn, or the United States' planned withdrawal from the Paris Agreement.

People ask me how I stay optimistic in such dark times. The truth is, I often do despair. Inaction, however, is never an option for those who believe that protecting the amazing panoply of life is our job in this world.

This article appeared in the March/April 2019 edition with the headline "What the World Knows."

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club