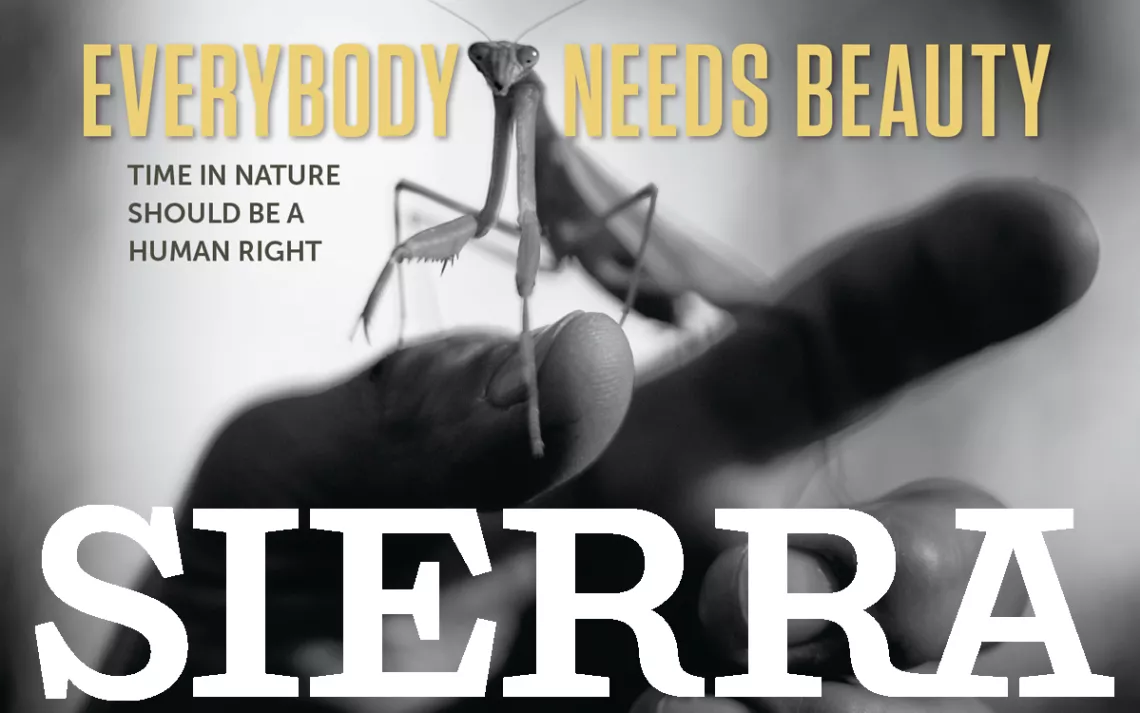

Everybody Needs Beauty

Nature should be equally available to all people

Human beings are animals. We weren't always the indoor, almost electronic species we are today. For most of our time on Earth, we lived as other animals do–in close intimacy with nature. The digital age in which we find ourselves is a mere blip in the span of human history. Consider this: If we converted Homo sapiens' 200,000-year history as foragers and farmers into one day, our 30-year flirtation with virtual reality would be the equivalent of 13 seconds.

What used to be daily acts of living–experiencing the sound of running water, the smell of soil, the sight of the night sky–are now abstractions for many of us. This alienation comes at a real cost to our psychological and physical well-being. For many, anxiety and depression have become hallmarks of the modern condition (seven in 10 American teens say anxiety and depression are major problems among their peers). Obesity and diabetes are on the rise globally, as are deaths related to cardiovascular disease. Our self-imposed isolation from the physical world is making us sick.

Now, new research has confirmed the old folk wisdom that time spent outdoors is essential. In her book The Nature Fix, Florence Williams reports that as little as 15 minutes in the woods can reduce a person's stress hormone levels. Access to green spaces has been shown to decrease income-related mental health disparities, while other studies have shown that the sense of awe people feel in nature can boost feelings of generosity.

Such findings are among the driving forces behind a nascent global movement to establish time in nature as a human right. As author Richard Louv details in our cover story ("Outdoors for All"), a growing number of teachers, doctors, and parents insist that "equitable access to nature is fundamental to our humanity as well as to the future of life on Earth." Advocates worldwide are working to establish individuals' connection to nature as a United Nations–recognized universal right, just as the UN has recognized every person's right to clean water.

This effort is so important because, as Louv notes, while the "benefits of nature connection may be universal . . . access to natural areas is not." For evidence, read Kaitlyn Greenidge's moving essay "In Praise of Public Beaches." When her family fell on hard times, Greenidge found a haven on the Massachusetts coast. "We were poor," she writes, "but the beach was ours." And yet, as an African American, Greenidge has at times felt unwelcome walking along the shore.

In a truly just America, every kid and every adult would have the feeling of belonging in spaces both public and wild. Since time in nature is essential to each person's well-being and pursuit of happiness, nature should be equally available to all people.

More than a century ago, in his book The Yosemite, John Muir declared, "Everybody needs beauty as well as bread, places to play in and pray in, where nature may heal and give strength to body and soul alike." Those words are as important as ever–only now there must be a new emphasis on the "everybody." The movement to establish a human right to nature is crucial and urgent; nothing less than our civilization's survival is at stake.

This article appeared in the May/June 2019 edition with the headline "Everybody Needs Beauty."

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club