Building an American Serengeti in Montana

The perils of rewilding ranchland with ranchers still on it

Photos by Charles Post

THE WORLD IS CHANGING, says George Horse Capture Jr. He worries that someday people "aren't going to know what the prairie looked like during the season of the spiders." In the golden days of late summer, when silk-spinning orb weavers have matured, early light slants across the grasslands of eastern Montana, and "the prairie, as far as the eye can see, is full of spiderwebs."

Horse Capture is a member of the Aaniiih, or Gros Ventre, tribe, living on the Fort Belknap Reservation, which is in the middle of an ambitious and controversial effort to rewild the northern Great Plains. Horse Capture was there when a herd of bison was released onto its reclaimed homeland; his eyes lose focus and his voice grows distant as he describes a gate being opened and the humpbacked beasts—the foundation of his people's culture—returning to the prairie. "Them are seeds," he says. "Things are being set right."

Nicole Johnson keeps the cattle moving toward a tallgrass pasture at the foot of the Judith Mountains. A ranch she leases with her husband, Lance, is located within the boundaries of the American Prairie Reserve.

Early European explorers of the Great Plains described a living bestiary. On the shortgrass prairie of what is now eastern Montana, Meriwether Lewis noted (with his characteristically bad spelling), "we can scarcely cast our eyes in any direction without percieving deer Elk Buffaloe or Antelopes. The quantity of wolves appear to increase in the same proportion."

Within a century, that epic concentration of wildlife was gone, and the area's original peoples, who thrived alongside the land's many creatures, were shunted to reservations. Homesteaders flooded in, and 270 million acres of luxuriant native grasslands were tilled, divided, fenced, and drilled in what environmental historian Dan Flores calls "the destruction of one of the ecological wonders of the world."

The destruction, however, was not total. Harsh winters and scant rainfall drove out many of the homesteaders, and the hardy few who remained primarily inhabited small towns and big ranches that left native prairie grasses—the ecosystem's foundation—largely intact. The Nature Conservancy identified the area in 1999 as the "Northern Great Plains Steppe ecoregion." In 2010, the International Union for Conservation of Nature chose it as one of four remaining temperate grassland ecosystems on Earth with the potential for large-scale conservation.

Lance Johnson's decision to cooperate with the reserve has not made him popular with his neighbors. "If that's what floats their boat, I'm fine with that."

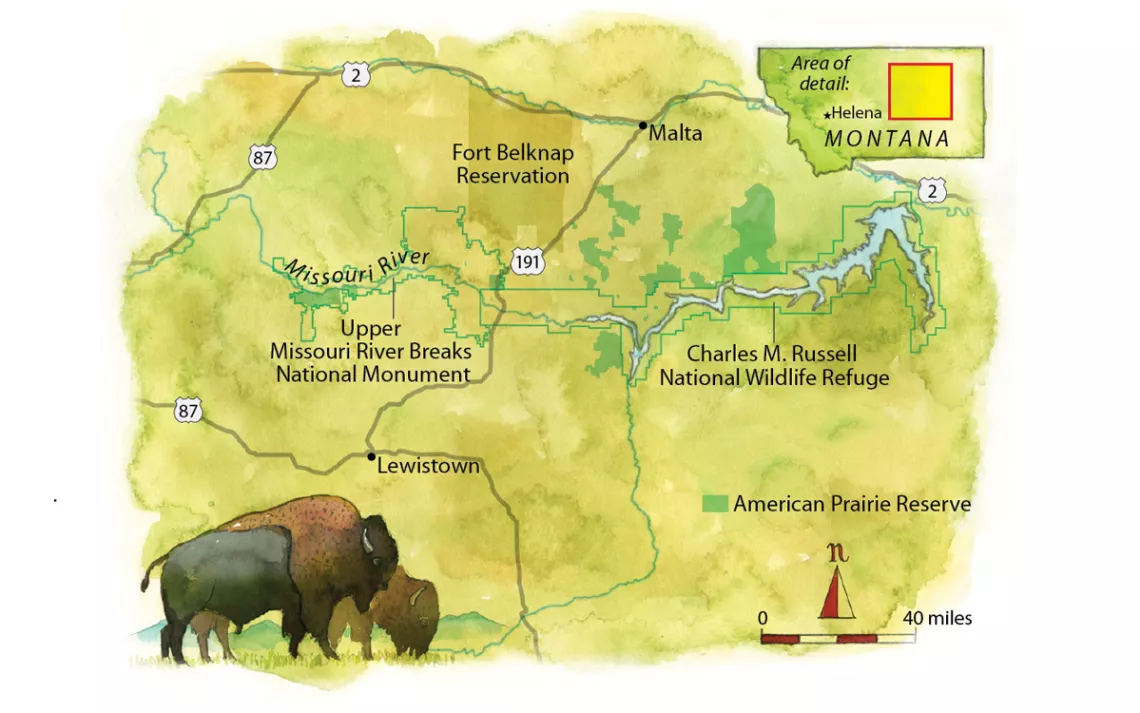

Curt Freese, a former World Wildlife Fund biologist, envisioned an alliance of conservation groups to create a reserve in eastern Montana. Two crucial building blocks were already in place: the million-acre Charles M. Russell National Wildlife Refuge and the 375,000-acre Upper Missouri River Breaks National Monument. Surrounding them are the Fort Belknap Reservation, the more distant Fort Peck Reservation, and seemingly unending private ranchland interlocked with Bureau of Land Management parcels through long-term grazing leases.

Freese started working with an entrepreneurial friend, Sean Gerrity, who had grown up in Great Falls, often hunting with his mother and father in the vast prairie lands. Gerrity had run a successful Silicon Valley consulting firm, working with companies like Apple, Intel, and Cisco. He saw private property not as an obstacle but as an opportunity. To save the prairie, why not just buy it?

In 2001, the two men launched an audacious plan. Their nonprofit organization would raise funds to buy area ranches as they came on the market. Using the refuge and the monument as anchors, they would gradually assemble a 3.2-million-acre wildlife reserve, half again as large as Yellowstone National Park. They would call it the American Prairie Reserve.

NONPROFITS AND LAND TRUSTS have purchased conservation properties for decades, of course, but seldom on this scale. The American Prairie Reserve sets itself further apart with its goal of fully restoring the landscape's biodiversity.

"Europeans killed all this stuff off so quickly, we never even had a chance to establish a cultural memory of an intact prairie ecosystem," says Daniel Kinka, the reserve's wildlife restoration manager. "Ask anybody in America to imagine a prairie—you see a red barn, cows, some barbed-wire fences. How many people see bison and elk and bighorn sheep and wolves and grizzly bears—a Serengeti image but with truly North American animals? We can bring that back."

Northeastern Montana's grassland ecosystem is one of the most intact left on the planet.

Biologists on the reserve's staff of 40, headquartered in Bozeman, are working to do just that: They're removing or modifying wildlife-blocking fences on former ranchlands and meticulously restoring habitat to attract species like swift foxes and prairie dogs. And they're reintroducing bison, with a vision of eventually hosting every species that once roamed those plains. Numerous ecological studies are being conducted across the landscape, aided by partnerships with field scientists from the Smithsonian Institution and the National Geographic Society, creating one of the world's most dynamic biological laboratories.

By most measures, the ongoing project has been a brilliant success. As of this writing, the reserve had purchased 28 ranch properties encompassing more than 400,000 acres in eight noncontiguous parcels. It had reintroduced 800 genetically pure bison. Now one of the largest conservation projects in North America, the reserve is well on its way to restoring the biggest grassland ecosystem on the planet.

There's only one problem: The descendants of the original homesteaders still live there. And they're raising hell.

"SAVE THE COWBOY. Stop American Prairie Reserve." The signs are everywhere in the cattle country and small towns around the reserve—on fences, barns, even banks. In 2017, 133 area landowners created an anti-reserve easement on more than 200,000 acres, prohibiting bison on their properties. Last winter, the Montana legislature passed a joint resolution asking the BLM to deny the reserve permission to graze bison. Two similar but stronger bills that passed later were vetoed by Governor Steve Bullock.

Wildlife restoration manager Daniel Kinka says, "We don't want to put ranchers out of business."

Resistance runs deep in Malta, Montana (population 1,997), the commercial center of the wide-skied plains north of the reserve. Leo Barthelmess, a community leader, says he won't speak with me if I intend to paint ranchers as rubes. After some assurances, he shares his address, and I head south from Malta on gravel roads bracketed by barbed wire that extend into a cow-speckled expanse, passing distant ranches and slanting, weather-worn structures succumbing to history.

This is the western edge of the Great Plains, where the wind-worn shortgrass prairie soon gives way to the vertical wilderness of the Rocky Mountains. It is some of the least inhabited country in the United States. The towns are small and distant, the people few and flinty. Like much of rural America, northeastern Montana has been depopulating since World War I, losing approximately 10 percent of its residents per decade. It's the kind of place that reminds you of the survival equipment you meant to stow in your trunk.

After 30-some miles, a century-old stone homestead house appears among a spread of outbuildings, a seasonal pond, and several hundred grazing sheep. This is where Barthelmess, 63, and his wife, Darla, raised three children. After welcoming me in (and asking me to remove my cap), they feed me homegrown hamburgers at their kitchen table alongside their son and several ranch hands. Then Leo tells me about his life.

They're the "newcomers" here, Barthelmess's family having moved in 1964 from his grandfather's homestead near Miles City, 250 miles south, because his father saw room for growth. Working the ranch with him are his wife, brother, and son (a professional horseshoer) along with a sheepherder from Mexico and an apprentice. His daughter and her husband grow organic kamut wheat at a farm up the road. As president of the Ranchers Stewardship Alliance, Barthelmess works with conservation groups in the region to restore native grasslands. He harvests seeds of native western wheatgrass and sells them to other landowners. He wins awards for his stewardship and speaks at grassland conferences.

A prairie dog

"We're trying to do cooperative conservation to help these communities, because these communities are diminishing," he says in a quiet, firm voice.

Barthelmess would appear to be an ideal ally for the reserve—except that he views the organization as a conquering army, one his community must fight with every sinew. His would be a plum property, yet it's clear that Barthelmess would rather lie in front of a charging bison than sell to the reserve.

"The APR came, and their media blitz was 'You guys have been doing it wrong all your lives, and we're about to buy you all up because you're all broke,'" he says. "They came in and insulted the culture and said, we're going to replace you all with bison."

This isn't quite the reserve's message, of course, but today APR staff do acknowledge that their early approach had unforeseen costs. "We were trying to raise money and convince donors we could be successful with property acquisition," says Pete Geddes, APR's vice president, who has a background in free-market conservation strategies. "If we had more resources, we probably would have spent a lot more time focusing on what we call our Montana reputation. Those were trade-offs we had to make."

The fundraising strategy has paid off—since its founding, the reserve has brought in $156 million, much of it from Silicon Valley luminaries. But its focus on "saving the prairie," a concept that appeared frequently in its early literature, inadvertently insulted the area's proud ranchers, who believe strongly in the nobility of their work. By skimping on consulting with locals, APR allowed misinformation and rumors to run riot. Many ranchers are convinced the organization is hell-bent on wiping them off the map. The seeds of resistance—perhaps inevitably, perhaps not—were sown deep.

A western meadowlark

It doesn't help that APR could not have created a bogeyman more precisely calibrated to alarm rural America: tech bros from the coasts with huge sums of money scooping up ranchland and trucking in free-roaming wildlife. You might as well deliver the bison in black helicopters.

Things have gotten so bad in Malta that reserve employees often sit in isolation at community events. When told I'm researching a story about how ranchers and the reserve might work together, a gray-haired woman behind a motel counter roars, "Hell, no!"—even though she stands to directly benefit from increased tourism. Says Barthelmess, "If the Ranchers Stewardship Alliance or myself try to engage with them, we would lose all our community support."

Barthelmess is proud of his 25,000-acre ranch and offers a tour in his pickup—an ATV loaded in the back, as always, in case of a breakdown in some remote coulee. We rumble up a knoll, the high point of the property, with vast views of the prairie sea around us. It's Barthelmess's favorite spot, which he admits to visiting for "introspective moments." He shows me the grooves of wagon tracks leading to an old homestead. Native grasses stabilize the soil; there's also non-native crested wheatgrass, planted by the government after homesteaders abandoned the land in the 1930s. Nearby is a sage grouse lek, where 16 roosters were counted last year. Mule deer browse in the distance. The song of a meadowlark rings through the air.

"Does this look like it needs to be saved?" Barthelmess asks.

A golden eagle looking for its next meal

Balancing the needs of wildlife with those of the agriculturists who almost always surround protected natural areas is not a new challenge. Locals initially resisted the creation of Glacier and Grand Teton National Parks, now foundational to their regions' economies. Those at the reserve know they have work to do. Gerrity (who recently stepped down as president but continues to work on special projects) admits that it may take decades but says that they are introducing several efforts to bridge the divide.

"Everybody's struggling with this, and northeastern Montana could be a leader and a bright spot," he says with his typical optimism.

In Lewistown, a cowboy town of 6,000 where the smell of manure sometimes wafts through downtown, the reserve recently purchased a historic building on Main Street for a future visitor center, which it hopes will illustrate APR's growing economic benefit.

Eager to show they're good neighbors, reserve staff are also working to help ranchers in the area adapt to the increasing wildlife populations. In January 2019, the reserve hosted a Living With Wildlife conference in partnership with the National Geographic Society. Wildlife scientists, activists, and ranchers from around the world came to Lewistown and, along with a crowd of curious locals in wide-brimmed hats, shared coexistence strategies.

Near the end of the conference, a rancher in a black cowboy hat named Lance Johnson stood up to address a crowd with decidedly more PhDs than dungarees. He thanked the other ranchers there and encouraged researchers and activists to take care in how they spoke to them. (Some ranchers admitted afterward that they had felt talked down to.) Johnson said that he was working with the reserve and felt that he'd been treated fairly. "Like it or not, the world is changing, and as ranchers we have to find ways to adapt," he said. Despite the conference's good intentions, though, another rancher who works with the reserve abandoned his speaking slot at the last minute after associates in the area threatened to stop doing business with him. Outside the conference-center door, a 10-foot hay bale on the flatbed of a parked truck was hung with a "Stop American Prairie Reserve" banner. Across the street, near a semi and a livestock trailer flying the same message, Leah LaTray and several other ranchers stood in the snow and subfreezing weather.

A gopher snake pretending to be a rattler

"They don't want us on the landscape. We're not a part of their vision," LaTray said, her emotions raw. "And we're scared of their money and resources."

Ranchers have historically had an adversarial relationship with wildlife when dealing with the critters has increased operating costs and an already dawn-to-dusk workload. When I visited with LaTray later in the spring, she told me that when she and her husband returned home from protesting the conference, elk had infiltrated their stockyard, damaging fences, and were feasting on their cattle's hay. "We were laughing," she said. "'Living with wildlife'!"

APR plans to raise elk and bison numbers dramatically on its land and adjacent public lands—envisioning up to 40,000 and 10,000, respectively. LaTray wants to know where the animals will end up, "because they ain't staying on the reserve."

LaTray and many other local ranchers view the reserve as an existential threat. Though its backers can only buy land from willing sellers and at market rates—and occasionally get outbid on properties—ranchers are still concerned about the removal of those lands from agricultural production and the economic ripple effect it has on their communities. In the seven counties the reserve operates in, according to Commerce Department data, the hard reality ranchers face is a 42 percent decrease in inflation-adjusted income from livestock since 1970. Meanwhile, mechanization continues to reduce overall ranching employment.

A white-tailed deer doe

"In rural areas, people feel like they've been left behind, and they're pissed off," Geddes acknowledges. But he rejects the notion that the reserve is to blame: "Erase the American Prairie Reserve and those trend lines are going to continue."

Geddes also points to the story of Cliff Hansen, a former president of the Wyoming Stock Growers Association and later a Wyoming governor and senator, who publicly protested the 1943 expansion of Grand Teton National Park onto former ranchlands by defiantly running 500 cattle across the newly protected area. Later in life, a contrite Hansen acknowledged the park's economic and cultural value to the state and admitted, "I'm glad I lost."

"People say, 'Hey, conservation's GREAT and all, but I can't afford it,'" says Daniel Kinka, who was hired last year to problem-solve with the area's ranchers. "We're saying, 'Good point. Here's money.' We don't want to put ranchers out of business. Quite the opposite—they deserve to be paid for doing the right thing."

Kinka wheels his pickup onto a ranch road on the Fort Belknap Reservation just west of the reserve and drives to where a motion-activated camera is mounted on a fence post. As bison graze in the background (Fort Belknap has both a cultural herd and a commodity herd), he checks the images and finds a pair of night-roaming coyotes. That's worth $50—$25 per coyote—for the rancher here, who participates in the reserve's Wild Sky program.

A prickly pear blooms

Inspired by the Cheetah Conservation Fund in Namibia, which pays agriculturists not to kill the lanky felines, Wild Sky rewards wildlife-friendly ranch management. Leaving native prairie untilled is mandatory for participating ranchers, who can pick and choose from nine other steps, including installing wildlife-friendly fences, rejuvenating native plant communities through prescribed burns, keeping cattle out of riparian areas, and agreeing not to harm predators. For each step, ranchers are paid a premium of one cent per pound on annual beef sales, a sum that can exceed $10,000 annually. Wild Sky's goal is to avoid the Yellowstone effect—abundant wolves, bison, and elk crossing the park boundary (which ignores natural migration patterns) and getting harassed or even shot.

"To have a genuine, ecosystem-level conservation effect, we need soft boundaries and connected corridors," Kinka says. "This is where well-intentioned ranchers come into play." Bison are constrained on all reserve properties by perimeter fencing, which features top wires low enough for elk to leap over and barbless bottom wires high enough for pronghorn to limbo under.

The bigger question is what happens when wolves and grizzly bears arrive. Both species are already beginning to move farther east from the Rockies into the plains. Reserve managers envision a future—perhaps only a decade away—when the top predators inhabit the reserve in healthy numbers alongside every other native species.

"We can't be an isolated island out on this prairie landscape," Geddes says, pointing on a map to possible habitat corridors connecting the reserve to Glacier and Yellowstone. "In 10 or 15 years, when these [large carnivores] start to show up, we'd like the region to be prepared."

After July rains, the American Prairie Reserve is a sea of green.

Kinka hopes that the reserve can win over more locals with a suite of strategies, from smarter fencing to more-secure anti-bear storage to trained guard dogs. "They might say their ranch is not suitable habitat," he says, "but can a wolf or a grizzly bear walk across their land to get to the prairie reserve, where we've built a place for them?"

"THEY'VE GOT PICTURES OF BEAR from up higher here," Lance Johnson says, pointing at the Judith Mountains, rising above his Lewistown-area ranch, where Kinka has installed wildlife cameras. "They pay $300 per bear and I think got four or five different pictures."

Johnson, 50, is a square-jawed, blue-eyed, one-handed (as a result of being hit by lightning when he was driving a tractor at 12) fourth-generation Montana rancher who signed up for Wild Sky three years ago. Like most ranchers in the area, he was initially skeptical of the reserve. "I'm not necessarily against it. I'm not necessarily for it," he says in his steady voice, "but I side more philosophically with the rancher than I do with the APR."

Three years ago, he was seeking additional pasture for his cattle and, being a pragmatist unconcerned with how he might be perceived by others, secured a grazing lease offered by the reserve on a 50,000-acre ranch the organization had recently purchased along the Missouri River. (Ranch properties are often coupled to long-term leases on adjoining BLM lands that are binding as long as the land is grazed, effectively granting private control of public land. Leveraging this arrangement, the reserve hopes to eventually transition all cattle grazing to bison grazing as it gains approval from the BLM—a process that is already happening in some locales.) Johnson initially demurred when invited to participate in Wild Sky, but after looking into it, he says, "I decided I could live with it. The money was a good incentive."

Map by Steve Stankiewicz

While showing me around his 5,000-acre spread, he talks about the willows and aspens he restored in formerly denuded riparian zones after purchasing the land 20 years ago. A dramatic butte laced with snow soars to a sky speckled with rattling sandhill cranes and hawks on the wing. He admits to enjoying wildlife on his land—as long as it's "in balance."

"It's less important to me running the maximum number of cows here as it is about making a really good-quality ranch with good forage, good wildlife—a well-rounded ranch," he says.

Standing near a herd of Angus cattle beneath forested mountains, he points out grazing elk on the treeless lower slopes. Many ranchers are up in arms about expanding elk populations, but Johnson sees opportunity: He's made as much money guiding elk hunters on his land as he's made from ranching. He tolerates the large ungulates getting into his hay stores but often has to repair the fences they damage. The reserve recently gave him materials for wildlife-friendly fencing, which he's curious to try: "Maybe the elk can pass back and forth a little bit easier without tearing it down," he says.

Like most ranchers in the United States, though, he is no fan of wolves, which he considers to be "killing machines." He has begrudgingly agreed to not shoot them—another penny per pound. "If a wolf pack would focus on the elk and leave my cows alone, maybe I can learn to live with 'em," he says.

Johnson's willingness to work with the reserve has not made him a popular figure in the community. The long dirt road to his ranch passes any number of houses with "Stop American Prairie Reserve" signs, and Johnson says that he considers almost every one of those people friends—including LaTray, with whom he's had some "spirited discussions," he says. "But if you're always worried about what other people think about you, then you end up not doing anything. There's some ranchers that flat out won't hardly talk to us anymore because we're working with the so-called enemy in the APR. To me, that's unreasonable, but if that's what floats their boat, I'm fine with that."

Not every local community is hostile to the American Prairie Reserve's rewilding vision. "Most of our stuff is related to APR," says George Horse Capture Jr., who heads up the Fort Belknap Reservation's tourism branch, Aaniiih Nakoda Tours. "I can't help but see the economic opportunities for my people."

Last December, the reserve held a naturalist-guide training for its staff and several folks from Fort Belknap. (Neither Fort Belknap nor Fort Peck has taken an official position on APR.) Horse Capture, with his tightly pulled-back salt-and-pepper ponytail, envisions a future in which Native American guides lead river trips and interpretive excursions across the reserve and greater region. Before the training, he says, "we didn't have those kinds of capabilities. We are proud, and we are grateful."

Horse Capture talks about a friend, a fellow tribal member and rancher, who was opposed to the reserve. "Come down and see. Don't take my word for it," Horse Capture told him, and they visited the reserve together. Now the friend participates in Wild Sky (although anti-reserve pressure from his ranching neighbors was so great that he declined to speak to me for this story).

Horse Capture is empathetic regarding the deep angst many ranchers feel about being pushed off their land. "It upsets me that they would feel like that," he says. "Them are not good feelings. My people's been there."

One thing that binds everyone here—ranchers, biologists, Native Americans, motel owners, and activists—like spiderwebs in the grass, is their love of the prairie. LaTray described to me the feeling at sunrise on ranchland recently purchased by the reserve: "We left at daylight. The horses are quiet as we trot down a coulee. It's very peaceful; it's an amazing place."

Despite his skepticism about the practicality of the reserve and his allegiance to the ranching community, Johnson admits that he finds bison "majestic." He says, "I can even say a 3.2-million-acre functioning ecological system would be kind of neat."

Even Barthelmess can see the benefit of more visitors to the area. A few years ago, he says, he took out-of-town guests on a drive to show them his ranch. There were deer. A coyote ran across their path. A prairie-dog town was overseen by chirping sentinels. Elk lay under a pine tree near the Missouri River. And as they entered reserve land, they came upon a bison in the road. His guests were thrilled. The prairie was alive. "That's all it takes right there to start a business," Barthelmess says matter-of-factly.

Horse Capture points out that the Native American and Caucasian communities in the area haven't always gotten along—tribal members didn't always feel welcome in the area that is now the reserve when it was only ranches, he says. Today, he hopes that the reservation and surrounding, predominantly white communities like Malta and Lewistown can join together to market themselves as a destination for travelers and "break down old walls."

"We can all be stuck in our bad history," Horse Capture says, his hand sweeping across elemental country. "But let's see what the future holds for us, together."

This article appeared in the September/October 2019 edition with the headline "Building an American Serengeti."

MORE

For information on visiting the American Prairie Reserve, including touring by bike, go to sc.org/apr-info.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club