An Offering to History on the Mississippi Mound Trail

A writer explores the blues and her ancestry

The Mississippi Mound Trail links a number of massive earthen structures, vestiges of former Native American communities. | Photo by Ariel Cobbert

My friend Melanie and I joke that the tobacco brought us to Winterville.

We'd started our road trip through the Mississippi Delta by following US Route 61, otherwise known as the Blues Highway, which leads past dozens of sites—from dance halls to cemeteries—associated with the creators of this distinctly African American music style. That's what most people come here to see.

As we drove through the low-lying delta landscape, dominated by cotton fields and dotted with hickory trees, occasional glimpses of towering earthen structures in the distance piqued our curiosity.

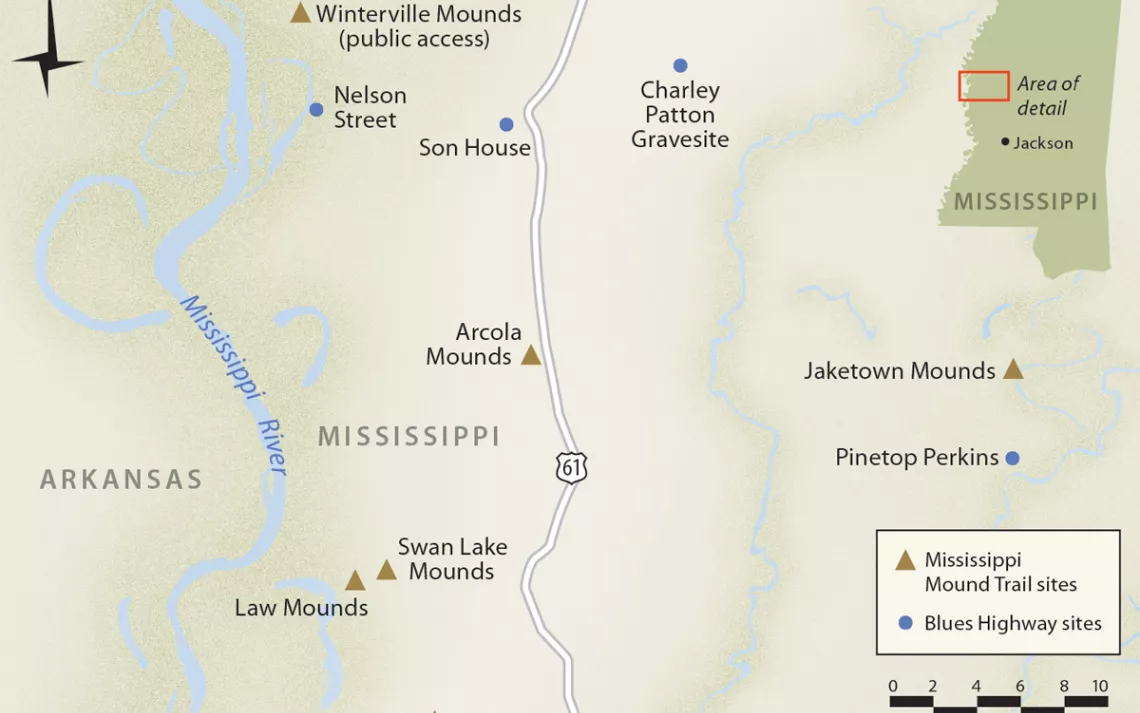

After a bit of googling, we learned that the Blues Highway runs semi-parallel to the Mississippi Mound Trail and that along 350 miles lie more than 30 pyramid-like structures built by Indigenous Americans. These impressive mounds are the remnants of entire cities: homes, places of worship, and burial grounds believed to have been built between 1500 BC and AD 1700 by the ancestors of the Natchez, Choctaw, and Chickasaw nations—Indigenous communities with roots on the delta. Although this area of the country is not commonly associated with Native American history and culture, there were once thriving communities here. The Grand Village site in Vicksburg was abuzz well into the 1700s, but its denizens, like those of neighboring mound-building societies, were eventually forced out by invading colonists. (Most of the mound dwellers' descendants were relocated to Oklahoma during the Trail of Tears forced marches, starting in 1831.)

The Mississippi Mound Trail is more of a road trip than a hiking experience—many of the structures are visible from Route 61 but are on private land and are not accessible without permission. However, four of them are open to visitors. After lunch on the third day, we stopped to walk among the monuments at one such site: the Winterville Mounds, located just outside Greenville.

Mel, who had been trying to quit smoking, broke down and joined two gentlemen standing outside the on-site museum for a cigarette. They happened to be the staff archaeologist and a representative from the Winterville Mounds Association. They said that the area had originally been home to many more such raised communities, but the structures had been leveled to make way for plantations—a heartrending thing to process, particularly for me, as someone with both African and Choctaw ancestry.

Map by Dolly Holmes

It's hard to say whether it was this story or the land itself that gave Winterville such a solemn air. Though the site was separated from the road by only the small museum and the parking lot, the area was silent other than the sounds of wind rustling the smattering of trees.

We wandered, mostly without speaking, along the trail that takes visitors through the center clearing between two of the remaining mounds. Mel, a musician, mused that she could sense the blues—the whole area felt steeped in that strange, almost comforting melancholy that blues so often invokes—and I could understand how that particular genre of music came to be born here.

The land also possesses a subtle undertone of defiance. The monuments on the Mississippi Mound Trail persist, despite all attempts to plow them under or ignore them out of existence—much like the descendants of the tribes that built them and those who worked the land against their will. Still here, still holding fast to important traditions, still making music out of adversity.

I was thinking of all this when I borrowed a cigarette from my friend and pulled out the tobacco. In some African and Native American traditions, tobacco is sacred and is used as an offering to the ancestors.

I didn't know if it was right or proper, but I decided to leave a little offering at the base of the largest mound at Winterville, where it's believed that the community held important religious and cultural ceremonies. On my knees in the grass before the overgrown steps, I touched the tobacco to my head and said a quiet prayer in memory of those who had lived here, those who endured, and those who were forgotten. It seemed significant in some way that I'd ended up here, in a place that so exemplified the struggles and the triumphs of both sides of my own family tree—and offering a little bit of tobacco was the best way I could think of to honor that feeling.

Weeks later, I received an email from Paul Hamel of the Winterville Mounds Association. He mentioned that only days after we had left the mounds, an elder, a descendant of those who had originally inhabited the space, arrived suddenly, in much the same way we had. He, too, smoked a cigarette with the two men outside the museum. He then climbed to the top of the largest mound and performed a ceremony, the likes of which hadn't, to anyone's knowledge, been performed in that spot for over 450 years.

It was hard to wrap my head around the story. Mel still jokes that my tiny gift prompted the site to call for someone who knew how to properly perform an offering. For me, the email raised more questions than it answered, but I was as deeply moved reading it as I was by my visit.

This article appeared in the November/December 2019 edition with the headline "Mississippi Serendipity."

Take a Sierra Club trip to the South. For details, see sierraclub.org/adventure-travel.

WHERE The Mississippi Mound Trail, semi-parallel to US Route 61

GETTING THERE The best way to experience the trail is by car. It consists of 33 sites, from the Edgefield Mound near the Tennessee border and Lake Cormorant to the Smith Creek site near Woodville. Only Winterville, Grand Village, Pocahontas, and Emerald are open to the public.

MUST-SEE Winterville has a museum that gives visitors an overview of the site's significance, its history, and the ongoing archaeological work being done, and Grand Village features a re-creation of traditional Natchez homes.

ETIQUETTE Remember that these sites are considered sacred by the Indigenous peoples of the area. Behave as you would in any religious space.

SIDE TRIP While you're in Mississippi, explore the legacy of the African American community that made this region an international music destination by visiting places like the Delta Blues Museum in nearby Clarksdale, the BB King Museum in Indianola, and the nightclubs of Farish Street in Jackson.

MORE bit.ly/mm-trail

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club