How One Composer Channels Climate Grief Into Orchestral Pieces

And why John Luther Adams turned from activism to art

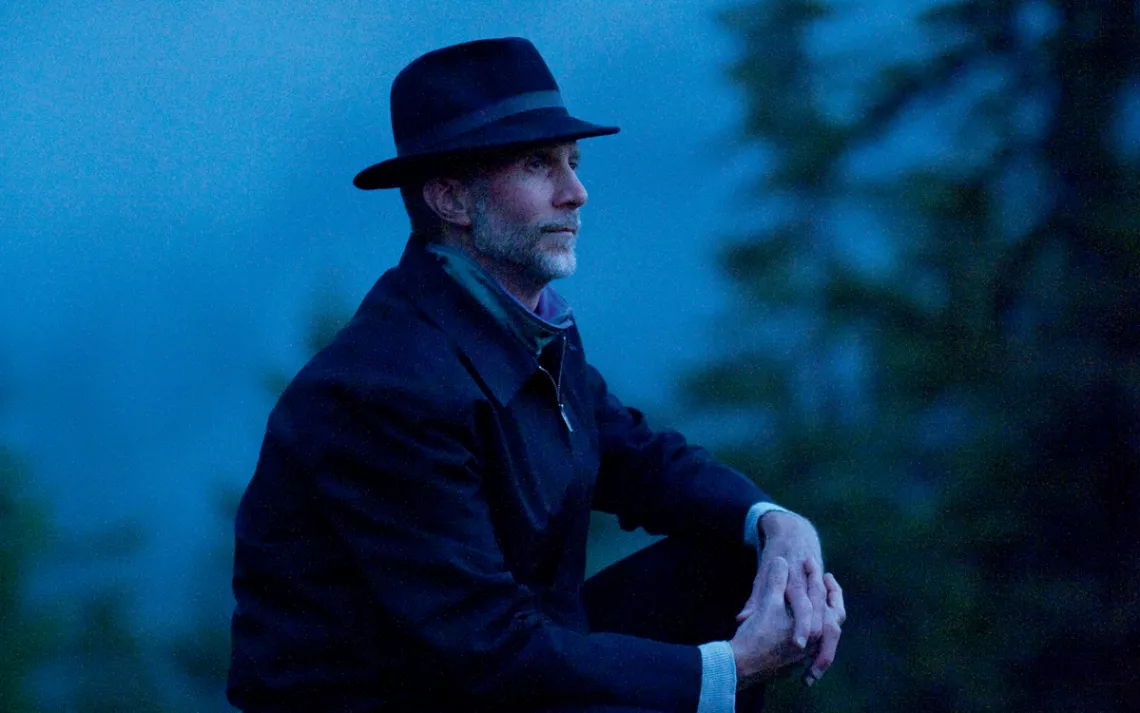

John Luther Adams left conservation advocacy to explore his environmental passions through music. | Photo by Donald Lee

Musical composer John Luther Adams lived in Alaska for nearly 40 years, 10 of which he spent alone in a spartan cabin in a black spruce forest near Fairbanks. It contained little more than a beat-up piano and a clock he kept in the refrigerator. When he moved into the cabin, Adams was an environmental advocate and lobbied to prevent dams, roadways, and mining operations from being constructed in Alaska. Later, he turned his energy to composing and eventually won a Pulitzer Prize, saw his music performed at the Lincoln Center, and won the favor of Taylor Swift, David Byrne, and Thom Yorke.

Still, when a journalist told Adams his life could make for an interesting book, the musician balked. He'd published two books about his music, but they were written in what he describes as "composer-polemical-philosophical voice." He wasn't confident that his other writing style, "eco-preacher voice," would work for a memoir.

Challenged by his wife, Cynthia, to make his writing "as beautiful as the music," Adams at last found an approach—lean, clear—and in September 2020, Farrar, Straus and Giroux published an account of Adams's time in the 49th state: Silences So Deep: Music, Solitude, Alaska.

Born in Mississippi, Adams spent his childhood hopscotching across the South and the East Coast because of his father's work. Though Adams never graduated high school, a voracious interest in music landed him a spot at the California Institute of the Arts.

In 1979, Adams was offered the executive director position at the Fairbanks Environmental Center. He spent years working with conservation advocates like Celia Hunter and Ginny Hill Wood, who in December 1960 persuaded President Dwight Eisenhower to establish what was originally called the Arctic National Wildlife Range. "The Arctic Refuge for me is still like the holy land," Adams told Sierra from his current home in New Mexico's Chihuahuan Desert. "It is the sine qua non in my imagination."

By the early 1980s, though, Adams was exhausted. He realized that he could be an activist or an artist, so he quit his job and in his remote cabin began to create intense and unconventional music "inspired by the big world outside our closed doors." He writes, "I took a leap of faith, in the belief that music and art can matter every bit as much as activism and politics."

John Luther Adams's Alaska cabin. | Photo by Dennis Keeley

Adams's music—typically played on acoustic instruments, with the occasional addition of electronics—seems enormous even in its quiet passages. He composed one piece, "Inuksuit," to be performed by up to 99 percussionists outdoors. And then there's "Ilimaq," a collaboration with drummer Glenn Kotche of Wilco, and "Become Ocean," which earned the 2014 Pulitzer Prize for Music and so moved Taylor Swift while she was listening to a Seattle Symphony performance that she donated $50,000 to the orchestra.

In 2014, Adams and his wife left Alaska for New York—citing the "accelerating reality" of climate change (the decade prior, they'd witnessed vast wildfires, mild winters, and early snowmelts). During a return visit, Adams discovered his old cabin was sinking because of melting permafrost. Still, he has only recently realized how much the climate crisis has affected his psyche and music.

"What I'm composing now is the most grief-filled music I've ever written," Adams says. "There's this sense of loss, of sorrow, of grief that pervades it."

Adams recently released two albums: Lines Made by Walking, featuring string pieces performed by the Jack Quartet, and The Become Trilogy, a box set of orchestral works recorded by the Seattle Symphony. He's also writing True Places, a follow-up to Silences So Deep, which covers his life since leaving Alaska.

At the moment, the onetime Alaskan is busy attempting to preserve his experience in the Last Frontier. "I spoke to someone the other day who said, 'You're mourning a world that has passed, a place that no longer exists. It's a kind of archaeological record of an Alaska that maybe is no more.'"

This article appeared in the January/February edition with the headline "The Sound of Climate Sorrow."

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club