Everybody Gets Frisky During a Herring Spawn

Sex, sashimi, and pelican stalking at the annual San Francisco Bay herring run

Illustrations by Lily Nie of Paperlily Studio. Watercolors by Kate Golden.

In early January, I woke up to a message on my phone that I'd been anticipating for months. It was a video from my friend Ann in Sausalito, taken in the predawn black on her houseboat's back porch. Seven little fish flashed silver as they jumped in a stockpot being used as a bucket. Xuân, her three-year-old daughter, yelled, "A big one!" as another fish jumped out of Ann's hands into the pot. "Happy New Year!" Ann's partner, Stephen, said to the camera. All of them wore pajamas.

In early January, I woke up to a message on my phone that I'd been anticipating for months. It was a video from my friend Ann in Sausalito, taken in the predawn black on her houseboat's back porch. Seven little fish flashed silver as they jumped in a stockpot being used as a bucket. Xuân, her three-year-old daughter, yelled, "A big one!" as another fish jumped out of Ann's hands into the pot. "Happy New Year!" Ann's partner, Stephen, said to the camera. All of them wore pajamas.

"OK," I wrote back, unusually awake for 6:45 A.M. "We are coming."

Practically every time my partner, Wes, and I visit Ann and Stephen, they crack open a jar of pickled herring. I still have several not-quite-empty jars in my fridge because I can't bear to finish one when I don't know when or if I'll be able to restock. That's the essence of a patchy resource, as the biologists call it.

If you're a school of Pacific herring heading in from the ocean with spawning on the to-do list, just swim under the Golden Gate Bridge with the tide, turn left, and you're there: Richardson Bay. Most of the spawn in San Francisco Bay happens in that smaller warehouse-, marina-, and houseboat-lined bay. The spot is far from intact wilderness and chock-full of predators, so it's not clear why the herring keep showing up. Some think it's because of the little freshwater streams that trickle into the bay and keep its salinity more consistent than in other parts of the bay that see big influxes of freshwater from the Sacramento–San Joaquin River Delta. But nobody really knows why the herring go where they do, or when they will go there.

The herring spawn is the biological event of the season in Sausalito. If you are a pelican, a gull, a cormorant, a salmon, or a sea lion, or my friends Ann and Stephen, it is Thanksgiving, Christmas, and Mardi Gras at once. If you are a herring, it is your world's biggest orgy, your life's purpose, and quite possibly the end of your days.

All year, Ann and Stephen prepare for this uncertain event, keeping binoculars, a cast net, and a bucket in the minivan. Each maintains a separate intelligence network of commercial fishers and other herring enthusiasts. Tips about birds and fish are currency, dearly held. A couple of spawns back, Stephen texted a well-known seafood provider about some frenetic pelican activity. This led him into an inner circle and got him a double-oh WhatsApp nickname that I cannot reveal. Ann's intel gathering only improved after she had Vi, six, and Xuân. She took to walking and driving the shoreline after their bedtime, listening for sea lions in the dark. She is not an early-morning person, except if she hears birds fighting . . . or sex-crazed fish slapping the hull of her houseboat. And then she is the first one up.

A HERRING SPAWN is kind of like an opera. "There's an arc to it," says Anna Weinstein, director of marine conservation at the National Audubon Society.

First comes an underwater prelude. The herring stage themselves in the deeper parts of San Francisco Bay, in a pattern called "holding." People who fish don't target them then, and the herring are too deep for the diving birds. What are hitting them hard are big predator fish: halibut, striped bass, sturgeon. And sea lions, which can weigh up to 700 pounds—"you see them porpoising around, and then you know," Weinstein says. Birds flock in the thousands in the middle of the bay—they know too. They are all responding to earlier cues, and to one another.

A spawn starts on an incoming tide, often after rain. A big spawn, 5,000 or 10,000 tons of fish, can last for days. A little one may be done in a few hours. The daily catch limit this year is two five-gallon buckets. I would be happy with one bucket.

As the fish come up in silvery hordes to spawn, brown pelicans wheel around and take turns diving. This is helpful for researchers and other spawn-watchers, because it's easy to see when pelicans swallow something. The flocks grow: grebes, gulls, cormorants. Anything that squawks or swims or scuttles.

Gorged animals get that post-Thanksgiving look. Sea lions, Weinstein says, are "overstuffed, just lollygagging around."

The female herring deposit sticky, translucent yellow-green eggs on eelgrass in the middle of the bay or on riprap at the edges, while the males squirt out their milt. The water all around the houseboats turns milky in a great fertile mess. Stephen has seen milt streaming whitely from a fish-filled truck onto pavement.

Then the caviar-eaters start in. Bigger gulls bully smaller gulls, while ducks try to get in on it between gulls. I have seen a picture of a seal utterly bedazzled with roe. Weinstein has seen an intertidal zone frothy with eggs completely cleaned out by the next day. The eggs that will hatch are laid a little deeper, she says. Why herring even bother to spawn in a zone that's such easy pickings for egg-eaters is another one of those unanswered questions.

THE MOST CRITICAL question is how many herring will turn out to spawn each year. As with every fishery, if we catch too much, the stocks could crash, affecting everyone who depends on them.

The number of herring showing up to spawn did crash in the winter of 2006–07. It happened the year after an outlier-of-outliers orgy and prompted the temporary shutdown of the Bay Area's small commercial herring fishery—which is one of the last urban commercial fisheries in the United States. Maybe this past winter the fish came back en masse, but thanks in part to the pandemic, state fishery managers weren't able to collect the data that would tell them so.

The number of herring showing up to spawn did crash in the winter of 2006–07. It happened the year after an outlier-of-outliers orgy and prompted the temporary shutdown of the Bay Area's small commercial herring fishery—which is one of the last urban commercial fisheries in the United States. Maybe this past winter the fish came back en masse, but thanks in part to the pandemic, state fishery managers weren't able to collect the data that would tell them so.

You may, as I did, murmur "climate change." Yes, climate has been weirdly variable in recent years. To cold-water-loving forage fish, much of that variability has been unfriendly—from the big swings between El Niño and La Niña to the late or record ocean upwellings caused by strong winds pushing water away from shore to the unprecedented marine heat wave of 2014–15 known menacingly as the Blob.

Herring numbers have been trending down, but climate is not the only reason. Overfishing could be a factor. Habitat destruction is almost certainly another—the eelgrass that herring lay eggs on has gotten trashed by waterfront development, chains dragged by moored or anchored boats, and the 2007 Cosco Busan oil spill. It has only recently started to recover. And all that doesn't even include the clam invasions. Clams snuck in via cargo-ship ballasts in the 1980s and have been devouring so much algal plankton, it's affected every other species above algal plankton in the food web.

In 2018, a team of scientists led by Bill Sydeman and Julie Thayer at the Petaluma, California–based Farallon Institute set out to explore which fish and climate data could help fishery managers predict the size of the San Francisco Bay herring spawn. It wouldn't be easy.

The four decades' worth of available data isn't very long in either herring time or climatological time. (In 1990, the ecosystem underwent a "regime shift" that made old data less relevant in predicting numbers going forward.) And the overall spawn size has recently become much more variable, making it harder to forecast and set appropriate catch limits.

Still, in that hot mess of information, the Farallon scientists teased out some simple, strong predictors of how many fish will show up to spawn: how large the spawn was the previous year, how many fish babies ("age zero" herring) were counted in the bay three years earlier, and environmental conditions in the fall just before spawning.

It's not just the size of the spawn but also the timing that makes it important. Because the spawn happens in winter, when not much else is going on foodwise, the herring are critical calories to help birds fatten up enough to survive their own breeding season. Herring are so important to surf scoters that these sea ducks time their migrations up and down the West Coast with herring spawns.

It may seem obvious that herring catch limits should be on the cautious side when tens of thousands of herring-eating birds, like common murres, die of starvation, or when a large, warm ocean blob shows up in herring town. But that has not been the norm for fishery management, which is usually taxed to the gills with just the basic task of counting each year's fish. People have been talking about ecosystem-based fishery management for a long time, and California's Marine Life Management Act requires it. But given the extra data needed, it's another thing to pull it off. The San Francisco Bay herring fishery is a test of whether this kind of management can work.

"If there's a place where this is possible, hopefully this is it," Thayer, principal scientist at the Farallon Institute, tells me. Thayer and Sydeman put together a framework for how the state can incorporate ecosystem indicators when it sets herring-harvest catch limits. In 2019, after some political wrangling, the California Department of Fish and Wildlife adopted a new set of regulations based on their approach. It isn't everything the scientists had hoped for, but Weinstein still considers it "groundbreaking" to have "a harvest-control rule that meaningfully takes predators into account."

Unfortunately, the big-picture forecasts don't particularly help me or the sea lions with the finer-scale question: Where do I have to be to get whatever herring do show up? Weinstein likens the process to tornado-chasing. Herring and bird sightings, rainfalls and tides twang like guitar strings in some primal, reward-seeking part of our brains, my fishing friends and I decide. Our minds strive almost involuntarily to calculate the patterns.

This obsession brings together people from a great variety of backgrounds: The birders, such as the rare-bird enthusiasts and those, like Weinstein, who delight in watching trophic-level showdowns. The Scandinavians, ready with pickling brines. The sushi-eaters, who prize the roe, called kazunoko in Japanese. Paella-makers with giant cast-iron pans.

This year, social media infiltrated the herring spawn. The Lost Anchovy, a kayak-fishing website and YouTube channel, mapped known spawn sites on the shoreline and showed people how to go about catching fish. For Ann and Stephen, the crowds and fear of the coronavirus overshadowed the exultation of connecting to nature and collecting a feast. They mournfully skipped the throngs—which made it all the more miraculous that the herring arrived at their back porch in January.

WE ARRIVED A FEW HOURS LATE, just after high tide; the herring were gone. We stuck around, unwilling to concede. When the afternoon tide came in, Ann and I went out on standup paddleboards. I brought a bucket and cast net, in case another spawn bloomed up and I got the guts to try something stupid.

Out on the water, sky merged with sea in a dank, heavy gray. We wove through sailboat moorings, hoping for a word with those who lived on the bay itself. No one responded. But we were not alone. All around us was the intelligence we needed that herring were near. Every piling as far as I could see had a pelican or a cormorant. Thousands of birds floated around us in great mixed-species rafts. The seals, normally lazed out on logs at the marina's edge, watched us from the water, all big eyes and whiskers. Sea lions had arrived like oafish tourists. They milled around us as though they were herding us. Rude.

Most creatures near us seemed to be conserving energy. The feeling was of time being paused. Occasionally some gulls would flare up in a tizzy, which from a distance looked food-related and therefore attracted some cormorants, which settled down once they saw it was just the usual gullshit over internal hierarchies. Enough squawking would eventually attract brown pelicans, which are so big I suspect they don't want to get up off the sofa unless the buffet is certain. At this point, nobody was getting anything. In the meantime, we all waited.

Alas, we and the herring were the very model of a predator-prey mismatch. Eleven fish were to be the weekend and indeed the season total. That evening, Ann filleted the herring they had caught and sliced it into tiny, shining piles of sashimi, then steeped the golden kazunoko—Vi's favorite—in soy sauce. It would have to get us through till next year.

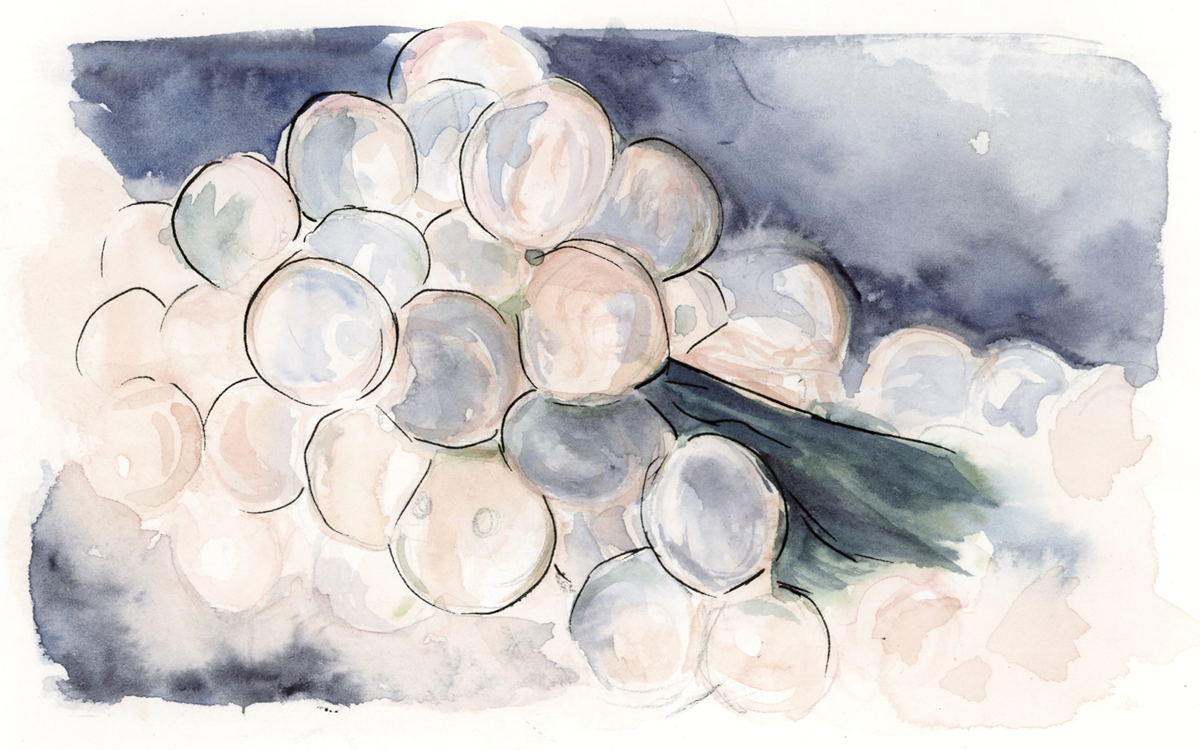

Pickled herring: the embodiment of Sausalito hospitality. Watercolor by Kate Golden, with reference photo by Stephen Allison.

Herring eggs are far more valuable than the fish flesh—commercially. Watercolor by Kate Golden, with reference photo by Ian McAllister/PacificWild.org.

Brown pelicans require up to four pounds of fish a day. Adults weigh eight to 10 pounds. Watercolor by Kate Golden, with reference photos by Paul Bragstad.

A pigeon guillemot that got lucky. Guillemots are puffin cousins. Watercolor by Kate Golden, with reference photo by Roy Lowe via Anna Weinstein.

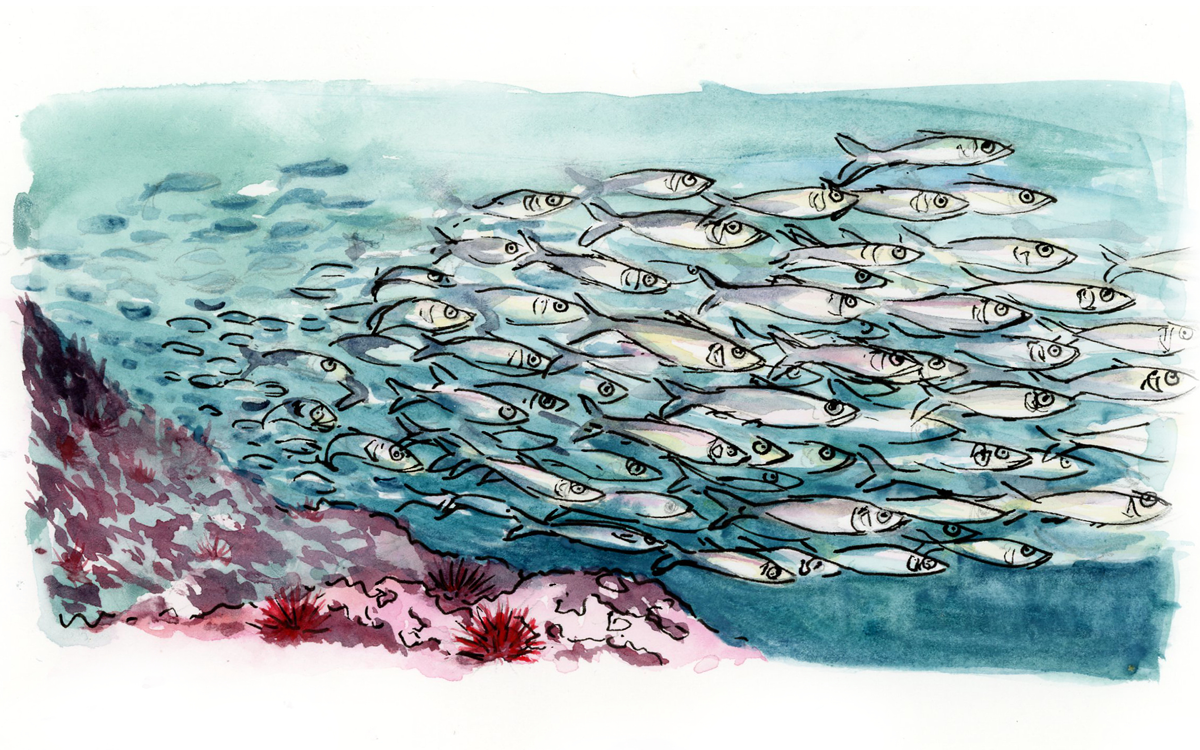

“It’s never a big run when you can count them,” Stephen said. Watercolor by Kate Golden, with reference photo by Stephen Allison.

“It’s never a big run when you can count them,” Stephen said. Watercolor by Kate Golden, with reference photo by Stephen Allison.

We all wait for the spawn. Watercolor by Kate Golden.

Pacific herring schooling in British Columbia. You wouldn’t be able to see them this clearly in murky San Francisco Bay. Kate Golden, with reference photo by Ian McAllister/PacificWild.org.

This article appeared in the Summer quarterly edition with the headline "Ocean's Eleven Zillion."

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club