Crypto Throws the Coal Industry a Lifeline

Bitcoin miners turn to dirty coal to satisfy their enormous energy needs

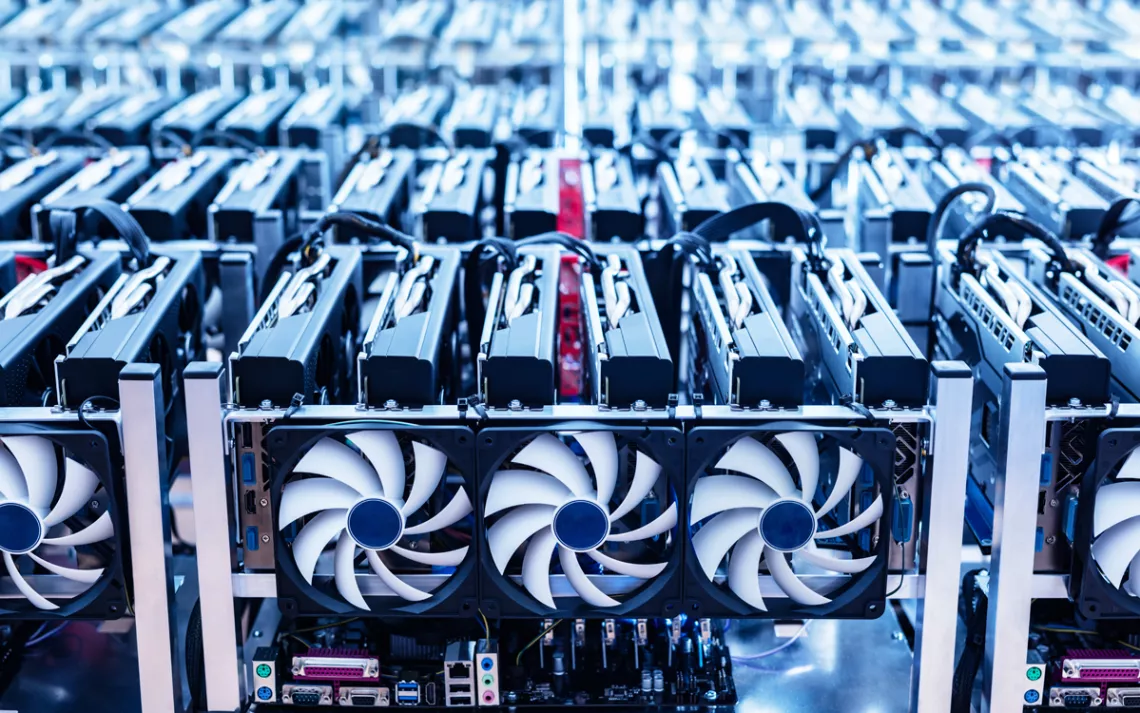

Photo by NiseriN/iStock

The Scrubgrass Generating Plant in Venango County, Pennsylvania, tucked into a thick forest next to a meandering stretch of the Allegheny River, burns 600,000 tons of coal a year. The resulting electricity goes no farther than the 2,000 computers in nearby shipping containers. They run day and night, powering the energy-intensive work of mining for Bitcoin.

A few years ago, the plant, unable to compete with cheaper gas plants, seemed close to retirement. Then, in 2017, it was purchased by Stronghold Digital Mining. The same salvation is being granted to defunct and declining fossil-fuel-burning plants across Appalachia and the Northeast: They have been fired back up and repurposed as giant generators for cryptocurrency.

In 2014, Atlas Holdings purchased a coal plant in the Finger Lakes region of New York that had been shuttered since 2011 and converted it to a gas plant. Initial Bitcoin-mining operations at the Greenidge Generation plant used 14 megawatts of energy, but the company plans to expand to at least 500 megawatts of mining capacity by 2025. Canada-based Digihost is running a once partially operational gas plant near Buffalo, New York, at full steam and is in the process of purchasing a second plant in Niagara County. In West Virginia, the Grant Town coal-burning plant hopes to bring itself back from the brink of bankruptcy by crypto mining.

Since 2021, when new laws in China devastated cryptocurrency mining there, the United States has become the sector's global hub—not least because it has lots of idled fossil-fuel-powered plants. Purchasing and reviving them is an efficient way for crypto entrepreneurs to make millions. But environmentalists are aghast at the lifeline being thrown to these dirty power plants.

"The amount of energy we're discussing here is tremendous," says Eilyan Bitar, an associate professor at Cornell University's School of Electrical and Computer Engineering. "In 2020, the amount of electricity consumed by the Bitcoin-mining network worldwide was greater than the usage of Argentina, Finland, and Washington State. It equates to roughly half a percent of the electricity produced annually worldwide. It's a nontrivial amount." A 2018 study published in the journal Nature Climate Change projected that over the next 30 years, Bitcoin's growth could produce enough carbon dioxide emissions on its own to raise global temperatures by 3.6°F.

A number of mining companies nevertheless claim that they're increasing their sustainability by converting coal-burning plants to gas or by purchasing carbon credits to offset their emissions. Stronghold Digital Mining touts the fact that its Scrubgrass plant—along with a newly acquired plant in Carbon County, Pennsylvania, and another dozen or so across the state—burns the low-quality leftovers of coal mining: bituminous or anthracite coal mixed with rock, shale, clay, and other minerals. Centuries of mining in Pennsylvania have resulted in thousands of acres of waste piles, some up to 200 feet deep. Some are on fire, deep underground. Others simply sit, choking the soil and emitting toxins into the air and water.

At Scrubgrass, that coal refuse is burned in what's called a circulating fluidized bed, where increased combustion makes it possible to draw energy from the low-quality fuel. The resulting ash is mixed with limestone to create a soil-neutralizing agent that can be spread on the former refuse pile site. William B. Spence, co-chairman of Stronghold, says that his company is a land-reclamation project with a Bitcoin-mining sideline. "Sometimes the perfect is the enemy of the good," he says. "I feel like what I do is very good. It's not perfect, but right now, it's the best thing that we can do."

But while the process may solve one issue, it creates another. Waste coal is the dirtiest coal because of its high levels of mercury, sulfur, chromium, and lead. In a circulating fluidized bed, more refuse is needed to produce the same amount of energy as regular coal, so the toxic byproducts are multiplied.

Stronghold used a loophole for Scrubgrass—classifying it as a mining operation—to survive Obama-era emissions restrictions that would have shut down the plant and similar refuse-burning enterprises. During the Trump administration, those EPA rules were loosened, meaning the crypto miners can continue generating immense amounts of power "behind the meter" without much restriction or oversight. And even if removing and burning coal refuse does help stem water-quality problems and prevent inextinguishable underground blazes, the waste piles aren't an unlimited resource, raising the question of what will happen when they're gone.

"I will make a pact right now," Spence says. "When all this waste coal is cleaned up, we're done."

Meanwhile, his company, like Greenidge, Digihost, and any number of other mining entities, is expanding fast. Stronghold went public on the Nasdaq in October at $19 a share, jumping by 52 percent on the first day of trading. The company now intends to acquire a third Pennsylvania plant and run nearly 30,000 mining computers by the end of 2022.

Last fall, the Sierra Club was one of dozens of organizations to sign a letter to Congress urging lawmakers to consider the environmental impact of cryptocurrency mining as the industry continues to grow in the United States. A group of Democratic lawmakers led by Senator Elizabeth Warren responded to that request when, in late January, they called on the largest Bitcoin miners to disclose details about their energy consumption.

"At the end of the day, when you burn that coal, you're producing a lot of greenhouse gases," Bitar says, "and that'll have a tremendous impact on climate change. It's not just a long-term issue. It's one we need to contend with today."

This article appeared in the Spring 2022 quarterly edition with the headline "Bitcoal Mining."

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club