Carry the Zero

Carbon dioxide removal is too important to be left to corporations and politicians alone

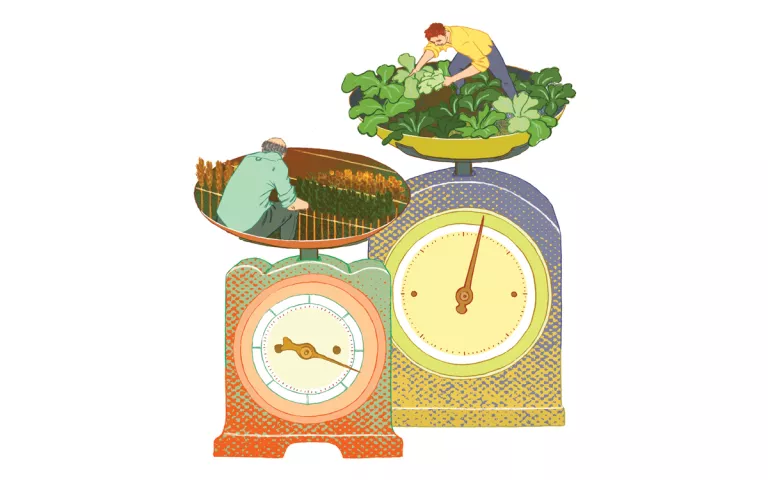

Illustration by Cat O'Neil

EVERY DAY, the planet's natural systems move vast amounts of carbon dioxide. CO2 flows from the atmosphere into the biosphere through plants and into soil through decomposition. It flows into the ocean and moves into rocks, where most of Earth's carbon is stored. Burning fossil fuels, cutting down forests, and plowing up soils have disturbed these flows, and this has sent Earth's climate careening out of balance.

This dangerous imbalance forces us to ask whether humans can intentionally, and beneficially, redirect some of these flows. And can we do so at a scale that would lessen climate damages, or even reverse some climate change impacts? Scientists are working hard to understand better what moving carbon around at planetary scales might mean for ecosystems and communities. Such research is a major scientific challenge. It's also a moral imperative, since we know that excess carbon in the atmosphere is causing harm.

What's clear is that some redistribution of carbon will be required to reach global net-zero emissions, which is necessary to fulfill the ambitions of the Paris Agreement. Here's where it gets tricky: Net zero does not mean zero emissions. It means that any remaining, hard-to-avoid anthropogenic emissions need to be zeroed out by carbon dioxide removal—that is, taking some amount of carbon out of the atmosphere and putting it someplace else.

It's reasonable to wonder if net zero is a greenwashing scam, because it sounds like one at first glance—and some governments and corporations appear to be using vague net-zero goals to procrastinate on decarbonizing. But scenarios used by the International Panel on Climate Change assume we'll need to deploy carbon dioxide removal at some scale for two main reasons. First, some industrial emissions are genuinely difficult to eliminate. The IPCC states that using carbon removal to counterbalance these emissions is "unavoidable" if net-zero targets are to be achieved. Second, since governments and corporations have spent 40 years delaying greenhouse gas reductions, we are now backed into a corner and will likely need to recapture some of what has already been emitted.

The question is not whether society should pursue carbon dioxide removal but how. And most important, who should decide the best ways to do it?

With a massive buildout of renewable energies, it is possible to fully decarbonize the energy system by mid-century. But manufacturing, aviation, and shipping are tougher challenges. Even with technological breakthroughs like electric arc furnaces for steel production and biofuels for aviation, the global agriculture industry would still have to decarbonize. Agriculture generates methane and nitrous oxide emissions and is generally considered the sector that is hardest to abate, given the need to produce affordable food for 10 billion people by midcentury. Many net-zero strategies rely on carbon dioxide removal (CDR) to compensate for agricultural emissions.

Beyond zeroing out agricultural and industrial emissions, carbon dioxide removal could clean up "legacy carbon"—carbon dioxide that has already been emitted. Even if the world reaches "true zero" decarbonization later this century, carbon-removal technologies would be useful in further reducing greenhouse gas concentrations. Removing historical CO2 emissions from the atmosphere could help stabilize the climate for future generations.

So, then, how much carbon removal might we need? In its most recent report, issued in April, the IPCC decided not to put a fixed number on it and instead emphasized that the final amount depends on the choices we make for reducing emissions in different sectors of the economy. Previous IPCC estimates for removals required over this century ranged from 100 billion to 1 trillion tons of carbon dioxide. That is obviously a massive range, and it illustrates that there is a spectrum of choices in eliminating greenhouse gases. We will need some carbon removal, but whether it is a modest or a staggering amount depends on how fast and how deeply we decarbonize.

The methods of carbon removal also matter. Conversations among climate-policy experts often pit biological carbon-removal approaches (like afforestation and planting offshore kelp forests) against technological approaches (such as bioenergy with carbon capture and storage). It might seem like a no-brainer: Putting carbon into forests and soils feels much better than building industrial infrastructure like pipelines and CO2 injection wells.

There are trade-offs with both approaches. Biological carbon sinks will eventually plateau, meaning they will take up carbon for a few decades and then become full. Both forests and soils are vulnerable to climate change itself; wildfires can send a carbon bank up in smoke. High-tech solutions risk enriching the same industrial interests that are fueling climate change in the first place. Such trade-offs explain why the Sierra Club's official policy calls for "supporting a diverse portfolio of environmentally acceptable and just CDR technological options to back up and supplement the natural systems solutions."

The question of how to remove carbon needs to factor in the people affected. Are carbon-removal technologies developed democratically? Do workers and communities get a fair say? Are the people who profit from carbon cleanup the same ones who made the mess? Seeing the how exclusively in terms of technology and engineering is a distraction from these more challenging and critical questions about the social and political how.

Above all, there is a real risk that carbon removal could distract from the effort to transition away from fossil fuels by creating a "moral hazard"—it might allow politicians and companies to focus on negative emissions while avoiding the harder challenge of ending fossil fuel production. The danger that carbon removal might delay the phaseout of fossil fuels is one reason that carbon-removal debates need the voices of grassroots climate advocates. People who care about climate justice can make sure that carbon-removal policies do not serve the interests of big corporations. They can keep the pressure on governments to ensure that the leftover emissions are truly hard to abate and set out a path for net zero to be a temporary step toward reaching true zero by the end of the century.

Given the risks of distraction and knowing that vested interests—from agribusiness and forestry to carbon traders and fossil fuel corporations—are tangled up with emergent ideas about carbon removal, it might seem simpler to just say no to carbon removal. Unfortunately, the science tells us that we are past that point. Without public guidance, the risk of carbon removal becoming a dangerous distraction is much higher.

If pursued wisely, under community leadership, carbonremoval projects could have benefits for people and ecosystems. Imagine regenerative agricultural and forestry projects with ecological and climate-adaptation benefits. Imagine industrial projects with community-benefits agreements guided by local residents' priorities. But such imaginings are bound to be elusive without grassroots advocacy to develop carbon removal in the public interest. This is the time to determine the shape of these future technologies and set the standards for their use. Carbon removal is too important to be left to corporations and politicians alone.

This article appeared in the Summer 2022 quarterly edition with the headline "Carry the Zero."

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club