Diving Beetles' Sexual Choices: Coercion or Promiscuity

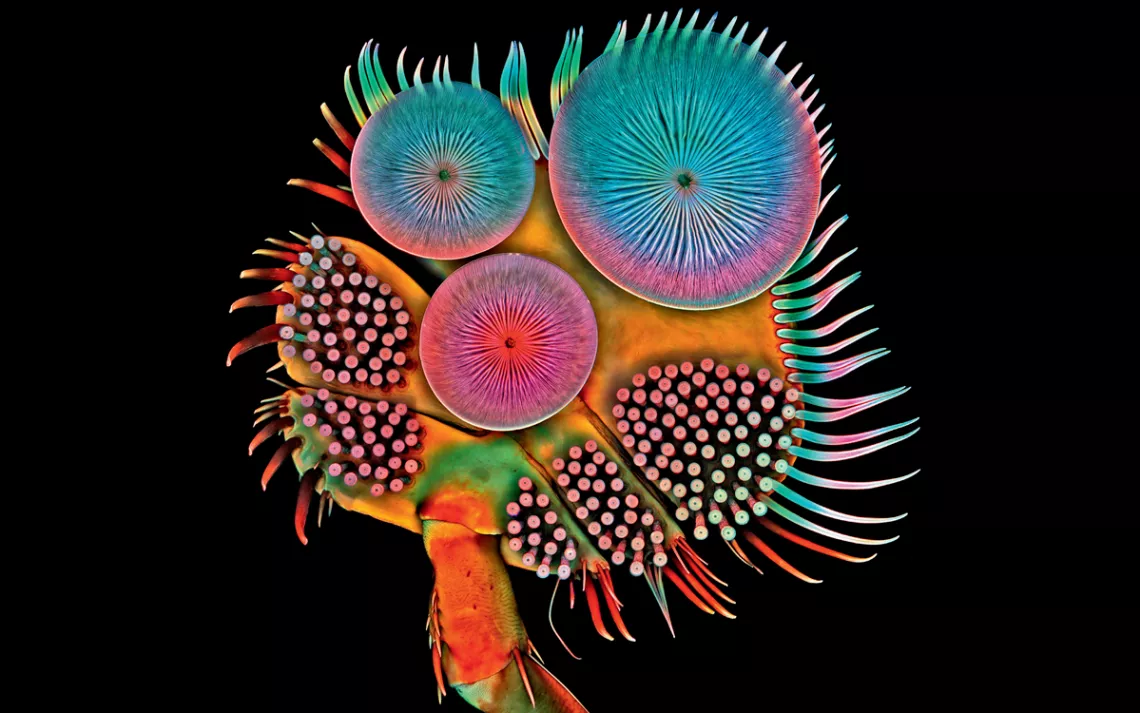

A colorful beetle with a dizzying sex life

Photo: Dr. Igor Siwanowicz

Lions rule the savanna, tigers rule the jungle, and diving beetles rule the pond. More than 4,000 species of these formidable predators ply pools, streams, and lakes stretching from the Arctic Circle to the tropics. Diving beetle larvae are particularly fearsome, with their sickle-shaped mandibles used to penetrate squirming victims' bodies and suck out the juices. Some species are appropriately nicknamed "water tigers."

Diving beetles' mating tactics are equally brusque, boiling down to two general, very different strategies: coercion and promiscuity.

Male diving beetles that employ the former strategy are conspicuously endowed with an array of suction cups on the undersides of their feet. If a male manages to torpedo after a female and catch her, he latches on to her back with his suction cups and holds her underwater, apparently to prevent her from breathing. A female will sometimes buck her Romeo off. If she doesn't, he forcibly mates with her. "Coercion is a phenomenon that's common out in nature," says Kelly Miller, an entomologist at the University of New Mexico. "I hesitate to use a particular word for it because of significant human overtones."

Female diving beetles are not just passive players, however. In this evolutionary arms race of sexual antagonism, many females sport deep grooves, hairs, or protrusions on their backs that interfere with males' abilities to grab and hold on. "Put a sucker on a glass pane, and it works well," Miller says. "But on a brick, it doesn't."

Sucker sex is relatively rare among diving beetles—just a few hundred species have evolved to do it. Most other diving beetles' reproductive rites involve insanely intricate vaginas that play host to Olympic-level competitions between the sperm of the females' many suitors. Feminine anatomy among these species includes superlong coiled ducts, tubes that lead to blind ends, storage chambers galore, and strangely placed internal hairs. Unlike their sucker-suffering cousins, females with labyrinthine ladybits will mate with any male that comes along. Sperm work together to navigate the incredible natural obstacle course of the female's body. They may link up to form trains, cluster their heads to create multicellular Cousin Itt–like masses, or contort into hoods that nest à la stacks of Dixie cups.

Female diving beetles may be able to exert some control over which sperm make it to the fertilization finish line—dumping some, metabolizing and digesting others, and storing favorites for future use. "It's the female's body, and she has the opportunity to choose," says Miller—a degree of reproductive autonomy greater than what the US Supreme Court offers American women.

Did You Know?

New species of diving beetles—depigmented, blind, and flightless—have recently been discovered in subterranean habitats around the world.

Diving beetles were eaten by Paleolithic people in what's now the American West, and today they're served in Southeast Asian food markets.

To save trips to the surface, some diving beetles carry a tiny water bubble under their shells—nature's version of scuba diving.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club