The Ultimate Compostable: You

High-tech or stick-em-in-the-ground, green postmortem possibilities abound

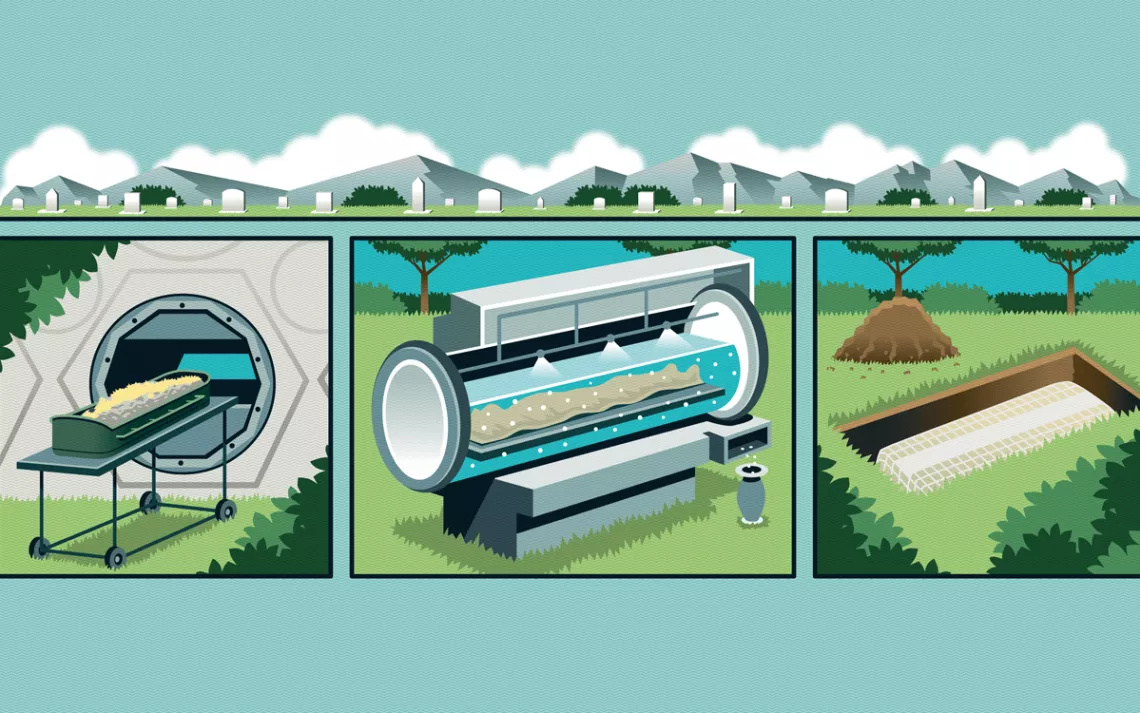

The typical US funeral ends with cremation or burial in a coffin sealed inside a concrete vault. But new, greener after-death possibilities have emerged. Alkaline hydrolysis is now available in most states, and Colorado, Oregon, Washington, and Vermont allow the composting of human remains. Or there's always a nice hole in the ground.

Composting

How It Works

It's like regular composting but more dignified. Recompose, a facility in Washington State, surrounds the deceased with alfalfa, wood chips, and straw in stainless steel capsules and periodically rotates them at temperatures between 130°F and 160°F. The result, after 30 days (plus a few more weeks of curing), is "a cubic yard of soil amendment."

The Hitch

Getting composted is cheaper than being buried, largely because it doesn't require real estate. But the long composting period requires a lot of maintenance, so it will still set you (or, rather, your heirs) back around $7,000.

Alkaline Hydrolysis

How It Works

The body is placed in a stainless steel container filled with 95 percent water and 5 percent alkali (i.e., lye) that is then pressurized and heated to 300°F. After three hours, all that's left are a brittle skeleton that can be crushed into powder and a liquid safe enough to be discharged into a municipal waste system. It costs $1,500 to $4,000, but boosters note that it results in 20 to 30 percent "more ash remains returned to the family."

The Hitch

Alkaline hydrolysis uses less energy than cremation, which requires temperatures well over 1,200°F (usually involving gas heat), but more than a natural burial. You may also need to spring for a bigger urn.

Natural Burial

How It Works

While "six feet under" is the classic grave-digging metric, the Green Burial Council recommends 3.5 feet to accelerate decomposition while still discouraging scavengers. "Animals are much more interested in living prey above ground," reads the council's FAQ. "We're just not that delicious."

If the soil is warm, loamy, and well drained, most bodies decay completely in 12 years. Flourishes meant to speed the process, like mushroom suits, are more for fashion. Plenty of organisms already present in the soil and in our own bodies are ready to tackle the job.

The Hitch

Natural burial has to happen quickly—ideally within three days of death and often involving a judicious use of dry ice before then. Plots are usually less expensive than for conventional burials but are still in the realm of $10,000. Geography is important: If you live in an area with a high water table, like much of Louisiana, earth burial is a challenge.

The Upshot

You'll generate the highest posthumous carbon emissions by being buried in an energy-intensive concrete vault. Cremation comes next, followed by composting and alkaline hydrolysis, with natural burial creating few, if any, emissions.

Remember that the carbon you can save after death is nothing compared with what you're capable of while still alive. Plan for your eventual demise, but make your impact here, working to leave the climate better than you found it.

This article appeared in the Fall quarterly edition with the headline "The Green Reaper."

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club