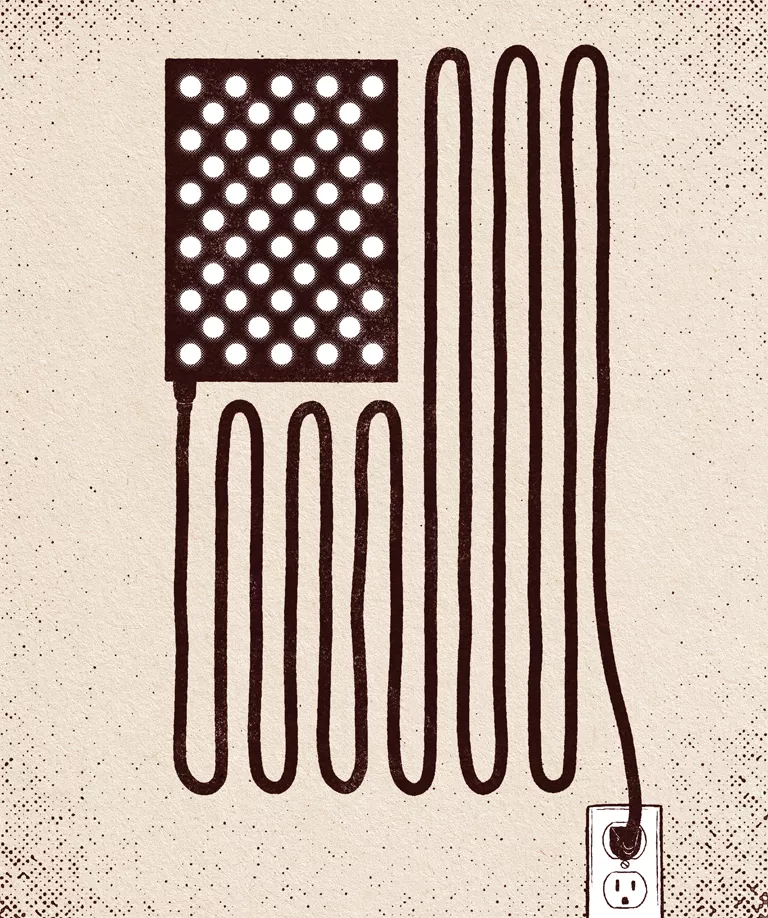

The US Electricity Transmission System Is in Gridlock

How a national macrogrid could accelerate the movement to electrify everything

FOR MORE THAN a year, the utilities that own various parts of the Midwest's power grid have been advancing the largest investment in electricity transmission lines in US history: more than 2,000 miles of added transmission at an estimated cost of $10 billion. The 18 new lines promise a suite of advantages. Most will thread through existing rights-of-way to tread lightly on ecosystems and communities. The new transmission lines are expected to generate over $50 billion in economic benefits, including cheaper power bills, as well as reliability enhancements that will prove priceless during extreme weather. Most important, plugging wind, solar, and battery-storage into the added wires should more than double the Midwest's renewable energy capacity, juicing the region's nascent transition off fossil fuels.

"It's not as shiny as a solar panel or an electric vehicle or a wind turbine, but this is absolutely the type of work you need if we want to decarbonize the economy," said Priti Patel, the chief transmission officer for Great River Energy, a nonprofit power supplier that serves rural Minnesota and provides an electrical lifeline to some of the state's poorest communities.

Electricity transmission and power-grid policy are like the middle child of the clean energy revolution—all too easy to overlook—and the details of power transmission may seem arcane. But energy-sector policy experts, environmental groups, government officials, and utility executives all agree: Smarter grid planning is the master key to unlock the energy transition.

No one would describe the US electricity system today as "smart." The network is a patchwork of undersized and aging lines. Few transmission routes reach the nation's best solar and wind resources, and most are unable to move bulk power between the various regional grids. Moreover, a bewildering array of entities with incompatible systems and competing interests must coordinate on upgrades, hindering modernization.

According to researchers at Princeton University's ZERO Lab, nearly half the emissions reductions promised by the Inflation Reduction Act between now and 2030 could be sacrificed if transmission upgrades continue at their current pace. Decarbonizing the United States by 2050 will require at least tripling its transmission capacity, other studies have found. Based on a mounting pile of pathway-to-net-zero energy studies, the Department of Energy projects that the US grid must incorporate over 2.5 terawatts of wind, solar, battery, and other clean energy tech within the next several decades. That's roughly 50 times more than the Midwest's planned 18-line leap will add.

Smarter grid planning is the master key to unlock the energy transition.

"To double or triple the capacity of our grid, it cannot continue to take 10 to 15 years to build each line," said Gary Moody, who leads the Audubon Society's transmission initiative. "We need to do it better and faster." Toba Pearlman, a Natural Resources Defense Council attorney who leads the group's Midwest renewables advocacy, described the Midwest's portfolio of proposed lines as "a big step forward." In the same breath, however, she said that the regional grid operator leading that big step, the Midcontinent Independent System Operator (MISO), was "inching forward" and had "miles to go."

The fact that even the nation's grid-building superstar is too slow and its innovation too timid to confront the climate emergency exemplifies the aching incrementalism plaguing grid expansion across the United States. According to the dominant narrative that has taken hold among politicians and many journalists, the number one hurdle to grid expansion is NIMBYism: the not-in-my-backyard campaigns by landowners and conservationists that routinely delay and often kill transmission projects. Some opposition campaigns are good-faith efforts to balance the needs of the energy transition with the desire to protect wildlands and wildlife; others are astroturf operations funded by dark-money fossil groups. In any case, opposition to new line construction thrives off what James Hewett, the US policy and advocacy manager at the Bill Gates–financed organization Breakthrough Energy, describes as outdated processes for planning and permitting transmission. "We've been doing the same things the same way for 100 years, and we've been building policies on top of each other," he said.

In response, environmental groups such as the Sierra Club and Earthjustice have floated proposals for cutting through the complexity to meet the challenges of this moment. Ideas include updating environmental review procedures to build consensus earlier in the siting approval timeline and modernizing the process by which the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission can help projects sidestep byzantine state siting procedures under its federal authority. But localized opposition to transmission lines is just one reason, and not necessarily the main one, that our transmission infrastructure has fallen so far behind what we need. The biggest barriers to grid modernization are structural: a morass of entrenched utilities and fossil fuel interests opposed to more competition from clean energy, parochial politics, archaic technology, and hard-to-resolve questions about who should pay for new lines.

The energy experts at MISO (pronounced my-so) understand those obstacles better than anyone. More than a decade ago, the Midwest grid operator crafted a smarter approach to planning, and its longtime engineering guru, Dale Osborn, produced the nation's leading plan for a 21st-century power grid. "The reason [transmission expansion] is so slow is because there are anchor draggers all over the place that do not want competition," he told me in spring. "Transmission planning is 90 percent politics."

Like an Interstate Highway System for electricity, Osborn's macrogrid would forge strong links between the country's weakly connected regions.

Rather than bolting new links onto today's balkanized power network, Osborn's design adds a bigger grid on top—a macrogrid—to efficiently shuttle power across the country and ultimately around the continent. Like an Interstate Highway System for electricity, Osborn's macrogrid would forge strong links between the country's weakly connected regions. Superhighways for power would not only speed up renewable energy deployment to electrify transportation and heavy industry but would also share power reserves as the country experiences more climate-change-intensified heat waves and winter storms.

As a kid, Osborn watched the construction of Interstate 80 transform rural Nebraska. Today, Osborn is visualizing macrogrid lines following the US interstates' rights-of-way to accelerate approval and cut costs. "They go everywhere we need to go," said the vital 77-year-old while polishing off a pile of Swedish meatballs and cured salmon during a lunch interview near the Minneapolis–St. Paul airport. (A year working outside Stockholm produced an enduring appreciation for Nordic cuisine, making the local IKEA cafeteria a favorite meetup spot.)

There's a lot going for Osborn's big-grid vision. The macrogrid taps technology that's already applied at large scale in Europe and China. And while the macrogrid's upfront cost is large—Osborn pegs MISO's share at $50 billion to $60 billion—many studies project even larger dividends. "The macrogrid will be at least 10 times bigger than anything underneath it. But the cost of delivering energy will be roughly one-quarter of current costs," Osborn said.

Osborn's vision faces daunting political and practical hurdles—his ideas involve more risk than most utility executives can stomach. Yet what's surprising, even after the Trump administration tried to bury Osborn's proposal, is how much momentum it has gathered in the nation's capital.

Patel is not sure the macrogrid vision has "reached political feasibility." But she's convinced that a national plan for a bigger grid will be required to make the energy transition a reality. And, as she points out, the macrogrid design has already cleared a giant hurdle: "What's already changed is that it's now actually a part of the conversation."

THE MIDWEST'S STATUS as a grid-planning pioneer germinated from the nation's ugliest case of transmission planning gone wrong. In the early 1970s, Minnesota's power cooperatives and state regulators were determined to tap dirty lignite-coal-fired power from North Dakota. Farmers were incensed that the required line would slice through some of the state's best soil, and they fought back. The six-year conflict devolved into guerrilla warfare, with farmers splitting the line's conductors with high-powered rifles and toppling its 150-to-180-foot towers. It took FBI intervention to put down the rebellion.

Over time, state and utility officials in the Upper Midwest increasingly heeded the inescapable message from the conflict: Consultation on transmission expansion must be early and open. True collaboration on the grid—among environmentalists, affected communities, regulators, utilities, and ratepayers—got a shot of fresh energy with the dawn of a new century and a newly competitive energy source: wind power.

Eagerness to tap potent wind resources aligned interests. Developers needed more transmission to build muscular wind farms. Farmers liked the prospect of payments for hosting wind turbines or power lines on their property, and politicians were lured by job-creation bragging rights. Environmentalists saw a solution to pollution. And even some smart utilities recognized that wind power was a winning investment.

In 2001, environmentalists and wind developers united in a novel advocacy project, Wind on the Wires, which set out to identify the grid upgrades needed to plug in and deliver wind power. The project (now called the Clean Grid Alliance) scored big wins in the early aughts that accelerated wind-farm deployment. The group backed proposed power lines in exchange for state-mandated requirements to reserve line capacity for wind energy. And it leveraged wind developers' long list of projects to encourage MISO to plan for seemingly unimaginable levels of wind power—gigawatt gales of clean energy.

Utilities had their own champion pushing for creative collaboration: Will Kaul, who was Patel's predecessor at Great River Energy. For years, the environmental manager turned transmission boss had a Rodney Dangerfield doll in his office that spouted the comic's trademark "I don't get no respect" zinger. But Kaul got traction exhorting utilities to team up on transmission while also collaborating closely with renewable energy advocates. "He did the 'Nixon goes to China' thing," recalls Clair Moeller, MISO's second-in-command. "He was among the first to see that we were in this together."

MISO launched a deregulated power market in 2005, and suddenly generators across its footprint—parts or all of the 10 midwestern states at that time, plus the Canadian province of Manitoba—had to bid for the right to sell power. Adding lines to connect more power plants would amp up the bidding, MISO's planners realized, and those savings could more than pay for the lines' construction. Lines to plug in wind farms, meanwhile, would also help utilities meet emerging state mandates for renewable energy.

Things really got moving in 2007, when midwestern governors, alarmed by "the crisis wind energy developers face," started agitating for a regional revamp. It was a bipartisan push, uniting the likes of Michigan's Democratic governor, Jennifer Granholm (who is now President Biden's secretary of energy), and South Dakota Republican governor Mike Rounds (who would later urge President Trump to withdraw from the Paris Agreement). The governors' role was "essential and catalytic," according to a recent analysis of MISO's planning process: "They helped identify the problems, added urgency to efforts, gave political cover (and pressure) to overcome objections, and they not only directed but empowered their regulators to act."

It took MISO and its stakeholders several years to work through critical details, including creating equitable mechanisms to share costs and benefits. Key solutions included assuring that all states got a piece of the resulting transmission and wind power developments and financing the upgrades by charging consumers across the region the same small rate increase. The new rules led to a set of transmission projects, proposed in 2011, that ultimately justified the time and effort. All but one of 17 lines survived the inevitable opposition that all transmission projects face and are operating a decade later—a batting average and timeline for the US electrical-grid record books.

MISO had cracked the nut for a multistate regional network. Wind-farm capacity in its footprint more than tripled over the decade when the new lines were joining the grid, beating the national average. And the Midwest's new transmission proves its worth during the extreme weather events that increasingly test grid reliability. When more than 4 million Texans lost power during 2021's Winter Storm Uri, the MISO grid held firm. And MISO customers were unaffected by Winter Storm Elliot in 2022—which caused blackouts over the holidays in Texas and the Southeast—as their utilities tapped diverse energy sources spread over a large area.

MISO's approach has become a national model. Last fall, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission proposed rules that would essentially tell every regional operator to do as MISO has done to prepare for an unprecedented acceleration of renewable power. For all its proven benefits, however, MISO's proactive, collaborative planning model had a larger role to play, Osborn thought. The grid guru had foreseen the regional dividends—more wind power and reliability were, after all, what his simulations projected. But he surmised that applying the logic of MISO's model to boost exchanges among America's big regional grids could pay even greater dividends.

The question Osborn confronted was one that often bedevils innovators: Would the solution scale? Simulations soon told him it could, as long as America's power engineers were willing to step out of their technology comfort zone.

OSBORN INTUITED THAT strengthening MISO's links to its neighbors would pay. There was plenty of midwestern wind available to help jump-start a transition to renewable energy in less-endowed regions. And MISO had proved that new links could pay for themselves by spurring competition in a virtuous race to the top.

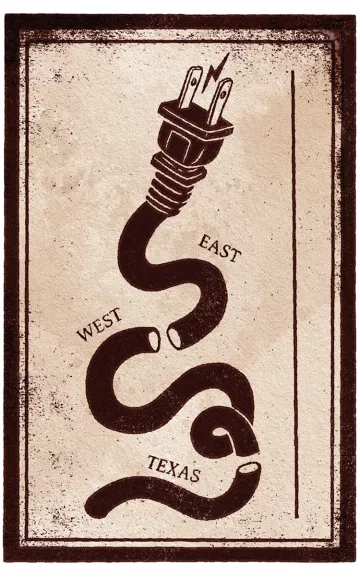

But these opportunities lay untapped because most US regions share weak electrical connections. Flows are particularly anemic between Texas and its neighbors, and between systems on either side of the Rockies. A technical barrier splits America into these three distinct zones: All use alternating current, or AC—the electricity delivered to outlets in our homes and businesses. And their electrical charges all flip 60 times a second. But the grids' 60-hertz AC waves are out of sync.

Even as MISO officials were crafting their first grid expansion, Osborn started pushing for exploratory studies simulating a future with big lines to bridge US grid divides. At first, the payoffs in his simulations were limited by the nature of AC power. Transmission added to the grid models performed inefficiently because AC produced at one point in the network didn't follow the straightest path to the point of consumption. Instead, the electricity spread to every line between those points, bulging out over the network like metal filings over a magnet.

So Osborn looked to AC's electrical alter ego: direct current.

DC power is all around us, flowing through everything from mobile devices and laptops to car batteries and solar panels. Osborn was well versed in the highest-voltage applications of DC power for transmission, having spent 19 mid-career years with the European company that pioneered them.

Europe and China have been building big DC lines for several decades. China's developments in particular have driven the technology to new heights. Over 30,000 miles of DC lines push coal, wind, and solar energy from northwest China and hydropower from the southwest to its heavily industrialized eastern seaboard. The biggest line can ship 12 gigawatts of power at a record-setting 1.1 million volts, dwarfing any sort of transmission capacity found in the United States.

Why not do the same here? Osborn knew that DC lines push power from point to point the way a pipe delivers water. He knew that DC lines bleed less power along the way than AC lines, enabling DC "pipes" to transport energy for thousands of miles. He knew advances in electronics were trimming the technology's premium price. And he knew that only DC links enable power to cross the electrical seams dividing America's three grid zones, and that only DC links could boost those flows.

A modeling study quickly proved Osborn right. The simulations explored a future grid east of the Rockies carrying 20 percent wind energy, with east-west DC lines pumping it to the densely populated East Coast. The model found that wind farms generating power on the Great Plains outcompeted many eastern power plants, which delivered some of the nation's priciest power. "The results showed we would drop the price of energy on the East Coast by up to 35 percent," Osborn said.

While that was good news for ratepayers—and the climate—Osborn's findings got a frosty reception from industry insiders. Evidence that Midwest wind power could outcompete coastal power plants horrified utilities in the East. MISO's Moeller felt the blowback at an industry roundtable in 2009 in Boston, where he tried to sell the mutual benefits of interregional transmission. "I got thrown out of Boston," he recalled. "The reaction was startlingly hostile."

Osborn was undeterred, and by 2014 he was sketching out the electrical equivalent of an exoskeleton super-suit: distinct networks of DC lines augmenting the existing grid nationwide, arcing over bottlenecks and seams to zap bulk power around the country. That summer, Osborn and a quartet of MISO interns turned his sketches into an optimized plan: 7,654 miles of DC lines that, in their simulations, shuttled about 30 gigawatts of electricity from nearly any point of generation to just about wherever it was needed. That's 23 times more energy than can currently cross the Rockies.

Osborn and a colleague dubbed it "the macrogrid" by riffing off the tiny self-sufficient microgrids that were all the talk among engineers at the time. The name stuck, and the macrogrid began to get attention. In 2016, Osborn, nearing retirement, convinced the Department of Energy's National Renewable Energy Lab to include it in America's most sophisticated grid simulation to date.

The Interconnections Seam Study projected that the MISO-designed macrogrid made the entire US power system more efficient and reliable. Linking complementary resources—such as winter-peaking midwestern wind power and summer-peaking California solar energy—cut costs while also increasing the nation's renewable portfolio. "In terms of utility projects, that's a no-brainer. You should do that," Osborn said. "Except that it affects a lot of people's bonuses."

The simulated macrogrid would shut down far more fossil-fuel-fired generators than the simulated DC lines that got Moeller flamed in Boston. It would save consumers billions—roughly 2.5 times more than the macrogrid's projected $80.1 billion cost to build. And the inevitable blowback from powerful interests was searing. When the National Renewable Energy Lab began reporting the seam study findings endorsing DC transmission, the Trump administration shot the messengers.

Closing coal-fired power plants en masse was off-brand for Trump. So when a political appointee saw an early presentation of the study's findings, the official alerted higher-ups, and agency brass put the squeeze on the lab's leadership. Within days, the research team was grounded, and its work was buried. The Interconnections Seam Study—and several dozen other inconvenient energy reports—would not begin to resurface until two years later, after I documented the cover-up for Seattle-based InvestigateWest in The Atlantic and Congress demanded that the study be released.

To Osborn, it felt like déjà vu. In his first years at MISO, he'd helped a utility in Michigan explore a DC line to expand its connection to the Midwest grid. The proposed DC line would have cleared a grid bottleneck that constrains power flows to this day. Unfortunately, it also might have required another utility within MISO to make payments. When that utility's CEO called MISO's and threatened to quit the market, Osborn found himself reassigned to lower-level work. "I was removed from that study," he said. "That changed a lot of my career."

Similar machinations—driven by parochial interests and profits—would come to chill MISO's entire planning operation toward the close of Osborn's career. The freeze started when MISO welcomed New Orleans–based utility Entergy into its market.

Entergy joined MISO under duress. Its subsidiaries supply power from Arkansas to East Texas, and the company had been abusing its regional monopoly. Federal antitrust officials gave the utility an ultimatum: Join a competitive regional market or suffer a breakup of its holdings.

MISO provided a safe harbor for Entergy and its fossil-gas-fired power plants. The thinnest of transmission capacity linked the Midwest and the Gulf states, limiting competition from other MISO generators. And Entergy lobbyists and its representatives on MISO committees found myriad ways to keep its turf safe, raising seemingly endless issues that stalled grid upgrades.

As longtime midwestern grid activist and Clean Grid Alliance director Beth Soholt told me in 2020, Entergy successfully "filibustered" MISO's consensus-based grid-planning process. "Entergy has done everything in their power to block another [grid expansion] portfolio," she said at that time. (Entergy did not respond to Sierra's requests for comment.)

The competition-blocking grid freeze at MISO shows why regional and interregional transmission—especially a gridlock-clearing scheme that's as bold as Osborn's macrogrid—is so hard to build across the United States. The fundamental force at work is the market power exercised by electricity generators—a power that is carefully safeguarded by the utilities' political enablers in Washington, DC, and state capitals.

MISO GOT ITS planning mojo back and reclaimed its pioneer status a few years ago, when midwestern regulators got worried about the grid again and overruled Entergy's filibuster. Pent-up demand for transmission quickly produced the 18-line portfolio that midwestern utilities are busily selling to communities and regulators. MISO made another bold move earlier this year when it released preliminary sketches of further transmission plans that include big DC trunk lines.

For sure, many of the ideas of a hoped-for national macrogrid remain at the stage of conceptual studies and simulations. But signs of growing ambition are showing nationwide, including some real-world progress in the West. In June, after 18 years of planning, construction began on the first substantial independently developed transmission line in the country—a 732-mile DC line to deliver gigawatts of Wyoming wind power to California and Arizona. The shovels hit the ground only weeks after federal regulators approved another DC transmission project in New Mexico.

Aaron Bloom, who led the Interconnections Seam Study and now designs transmission projects for NextEra Energy, the world's biggest supplier of wind and solar energy, said grid planners have begun to grasp DC's transmission potential. He said NextEra is "actively pursuing" high-voltage DC projects of its own "across the country." Bloom argues that transmission planners need to increase their ambition and coordination. He said that even MISO's record-breaking plans represent "a thimble's worth, and we need a whole ocean of transmission."

What's remarkable—and, to a great extent is Osborn's legacy—is that a truly national grid of any sort may actually be getting started. It's certainly an accepted must-do among an expanding number of US activists, government officials, experts, and politicians. As former transmission boss Will Kaul put it, "Some kind of macrogrid is assumed by most people that are deeply involved in transmission planning and the energy transition. It's mainstream. That's huge, and that's Dale."

Bloom agrees. He said that Osborn's planning insights "helped justify the largest network builds in the country," and that his macrogrid design sparked today's "national conversation about continental power system planning."

Now, many advocates are looking for a push from Washington, DC. Billionaire Bill Gates has helped boost support by funding something called the Macro Grid Initiative. The research and lobbying campaign has attracted a broad range of supporters, including energy producers, labor and trade groups, and environmental organizations like the Sierra Club, the Audubon Society, and the Union of Concerned Scientists.

The White House is on board. Under President Joe Biden, the Department of Energy declared high-voltage DC technology a "critical supply chain" for the energy transition, and it has dedicated funding for planning long-distance transmission and developing the electronic converters that connect DC lines to the grid. National studies to be completed this year are expected to strengthen the case for interconnecting regions, and the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission is investigating whether it should mandate interregional power-exchange capacity.

One thing everyone agrees on: America has the power-grid technology it needs to confront climate change. As Moeller put it, mobilizing the financial and political will is always what holds up big infrastructure. Building the grid of the future, he said, is no different: "It's nontrivial engineering, but it's not an engineering problem. It's a political problem."

Osborn will be watching with interest. He's clearly proud of his contribution to expanding wind power and designing grids that could take it further. After retiring from MISO in 2017, he continued refining the macrogrid and talking it up at industry forums. "This has been a big part of my life's work. I have a real passion for it," he told me in 2020, as he fought to free the seam study.

Since the pandemic, Osborn has, like many, refocused closer to home. He's prioritizing time spent rowing his Adirondack guide boat and doting on his grandchildren. He may be done floating big energy ideas, but he's committed to doing whatever he can to give his grandchildren the best world possible—one with plenty of clean energy.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club