What Is Lichen?

Here's everything you need to know about one of nature's most symbiotic partnerships

Sulphur stubble (Chaenotheca furfuracea) | Photo by Stephen Sharnoff

During a stroll through a city or a forest, one may encounter fuzzy growths on trees and rocks alike. Are they lichens? Mosses? Algae? Often, people use these words interchangeably, but each refers to a distinct organism with its own raison d'être. Mosses are singular organisms; lichens are composites. A lichen is formed when fungi and algae (or cyanobacteria) enter a symbiotic partnership: The alga provides nutrients, and the fungus provides a body, or thallus, for the alga.

In her book The Lichen Museum, A. Laurie Palmer invites us to consider lichens' power to awaken our senses and compel us to be unrooted in time. "You are invited to 'occupy' time with lichens where they are, in place, while simultaneously imagining their massive global distribution, neither gathered up nor possessed, but alive locally and all over."

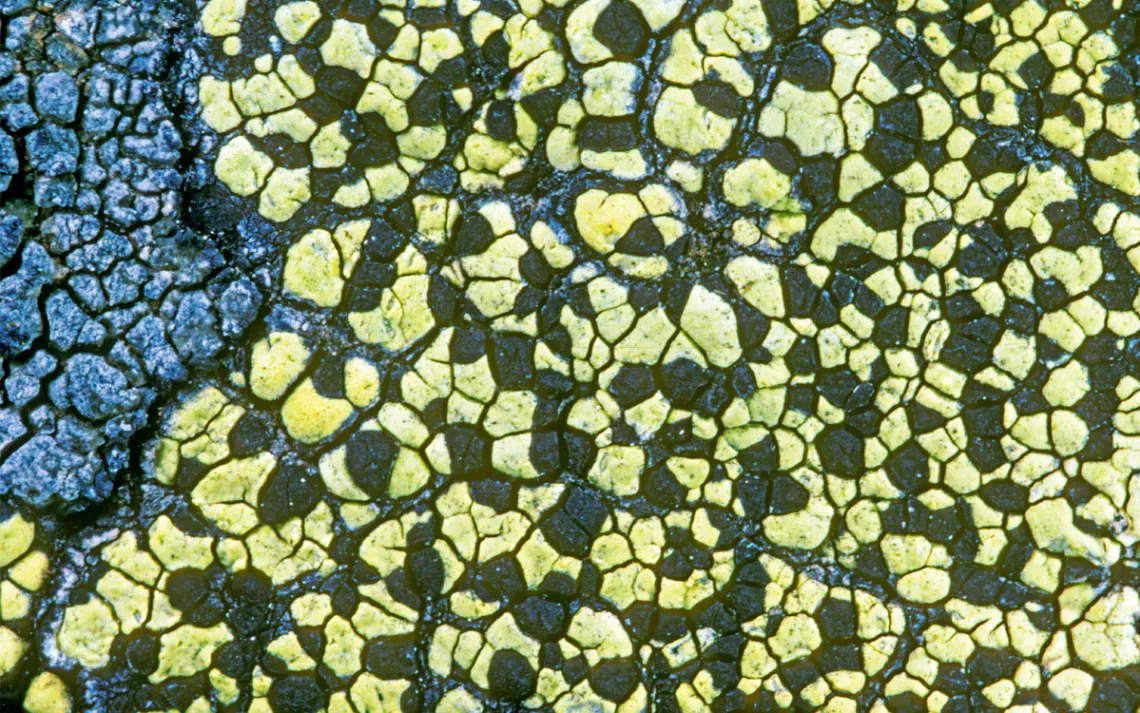

Map lichen (Rhizocarpon geographicum) | Photo by Stephen Sharnoff

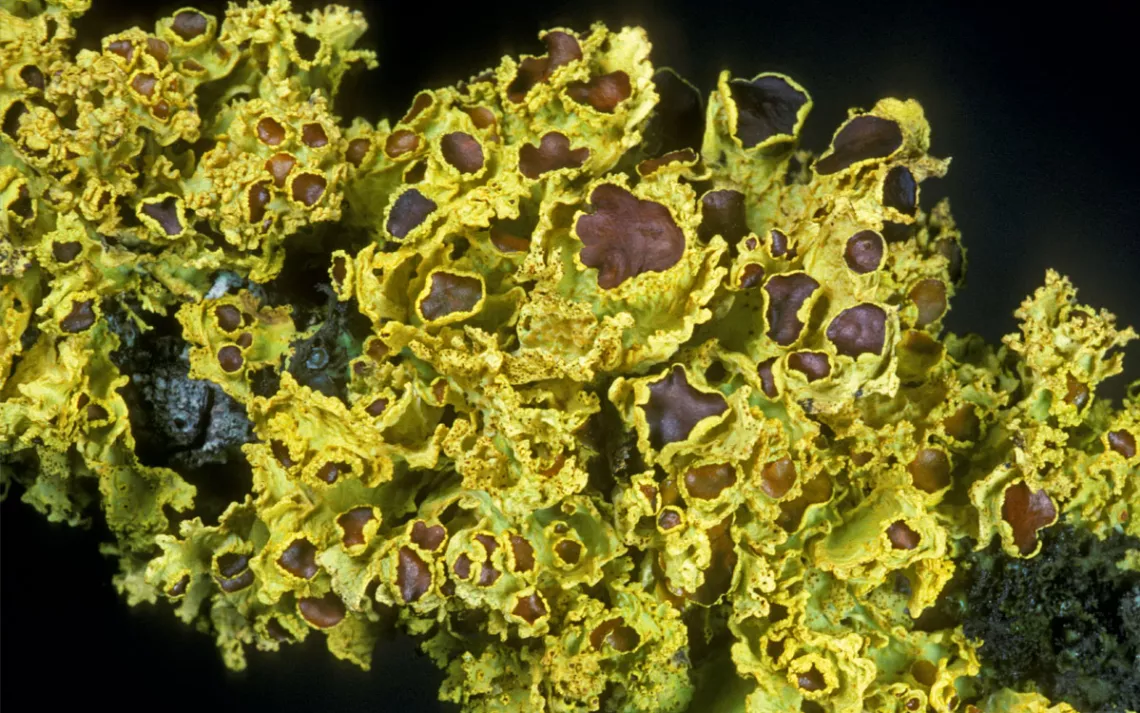

Lichens are everywhere. There are around 15,000 species, and they come in just about every size, shape, and color. One can find them in alpine regions, in intertidal zones, splayed across the walls of old buildings, and even making a home out of rotting clothes. The elegant sunburst lichen (Xanthoria elegans) often grows near rodent and bird perches. Brown-eyed sunshine (Vulpicida canadensis) is found in coniferous forests near water, covering branches in yellow-green fuzz. As primary colonizing species in most environments, lichens influence soil formation through a process of decomposition. That in turn helps create the right conditions for other organisms to occupy the area.

Brown-eyed sunshine (Vulpicida canadensis) | Photo by Stephen Sharnoff

Lichens are evidence of life enduring. But they are not immune to the impacts of human activity. They are sensitive to air pollution, and they bioaccumulate heavy metals such as cadmium and lead. Mountain crab-eye (Acroscyphus sphaerophoroides) is increasingly threatened by human development such as roads and mines.

Lichens are often keystone species: They provide food for some animals, shelter for others. They protect trees in inclement conditions. Lichens are the threads that hold the fabric of life together. Ranging from small clusters to vast, fiberlike tendrils, lichens adapt in response to ecological relations and re-create themselves in collaboration with surrounding stimuli. We are only beginning to understand their capacity for renewal.

Elegant sunburst (Xanthoria elegans) | Photo by Stephen Sharnoff

As essential as they are, lichens are also just fun to look at. On a walk one day, I was enchanted by the powdery chartreuse explosion of one species on a Douglas fir. Soon after, a hummingbird arrived to share my enthusiasm—picking at the hairy threads for its nest. Lichens serve as a reminder that beauty and survival are inextricably intertwined. They remind us of the interdependence of a world not fixed in time but infinitely linked in a delightful web of partnership and contingency.

There are about 3,600 lichen species in North America.

The US Forest Service National Lichens and Air Quality Database and Clearinghouse helps federal land managers assess the ecological impacts of air pollutants using lichen data.

Map lichen (Rhizocarpon geographicum) in the Arctic is believed to be about 8,600 years old, making it one of the oldest organisms on Earth.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club