How Does a Heat Pump Actually Work?

This humble technology reduces home emissions. Here's how it works.

THE CLAIM

About 10 percent of US greenhouse gas pollution results from our efforts to keep buildings warm in winter and cool in summer. That's because, to an embarrassing degree, standard temperature control still relies largely on burning the scum and dregs of the Mesozoic era.

But now there's a low-to-no-carbon alternative: the heat pump. In winter, it pulls heat out of the ground or air (even at very cold outside temperatures) and transfers it inside. In summer, it flips into reverse, pulling heat from inside and pumping it out. All it requires is a minimal amount of electricity—which, if it's produced from renewable sources, can make the entire process carbon-free.

HOW IT'S SUPPOSED TO WORK

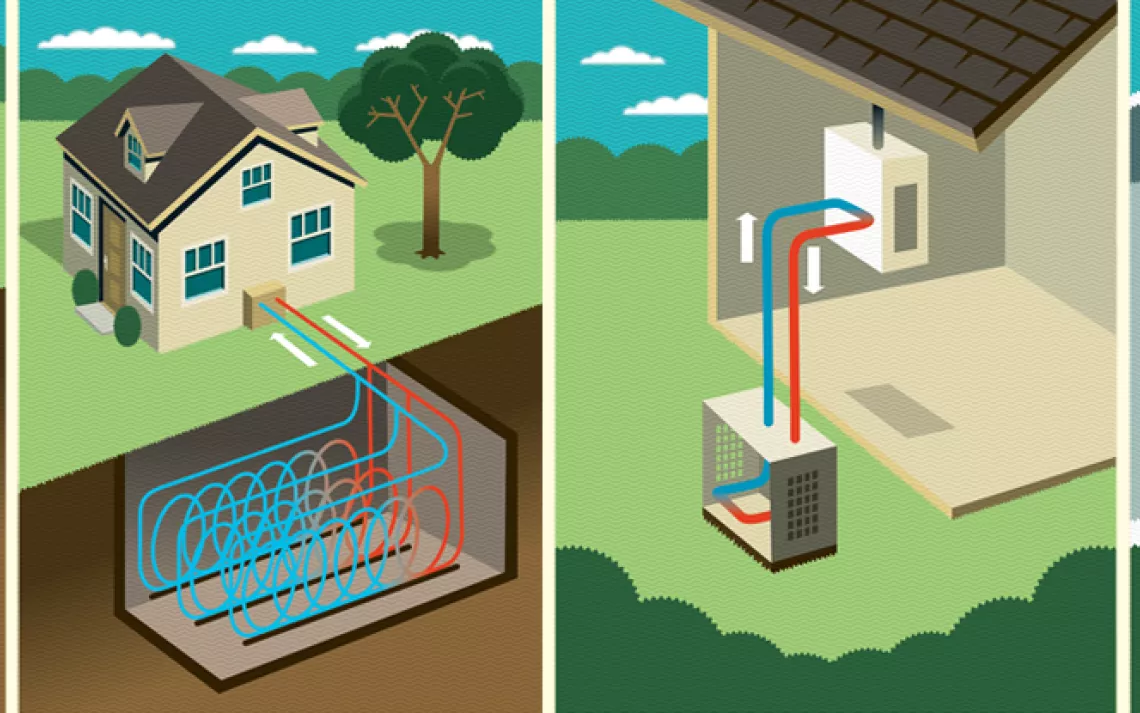

Y'all remember the second law of thermodynamics? Heat transfers from a hotter entity to a colder one. Heat pumps employ refrigerant to reverse that process: pulling heat from a cold area (ambient air or the ground in winter) and transferring it to a warmer one (your home), or from your home to outside in hot weather. There are multiple options to choose from, depending on availability, your budget, and your home's layout. Air-source heat pumps look like AC units, with outdoor and indoor units connected by a conduit. Ground-source pumps require refrigerant-filled pipes that absorb (or expel) heat from the ground or a body of water.

WHAT COULD GO WRONG?

Heat pumps are trickier to operate in very cold climates, and while the technology is rapidly improving, some systems require backups, which can increase the cost and decrease the carbon savings. (The Department of Energy has challenged 10 heat pump manufacturers to develop cold-climate models. Lennox was first out of the gate with one undergoing trials this winter; it could be available as soon as 2024.) Ideally, heat pumps should be designed to suit their circumstances—factoring in the size of the area to be heated and cooled, local temperature extremes, and the availability of outside ground or water.

And competent installers may be hard to find; the guy who put in mine, for example, didn't know that it required coolant. Finally, it's not like buying a new water heater when your old one fails. Installing a heat pump takes time, so you need to plan ahead.

THE UPSHOT

Heat pumps' operating costs can be dramatically lower than conventional systems', especially when the pumps replace baseboard or other electric heaters, or furnaces powered by fuel oil. But up-front costs to install one can be substantial. Air-source models are cheaper ($3,500 to $7,000, roughly) but are less efficient and require more frequent maintenance than ground-source models, which require excavation and can reach up to $22,000 installed.

The good news is that the Inflation Reduction Act includes tax breaks and rebates that could save qualifying consumers up to $8,000. And homeowners can pocket a home-energy-efficiency tax credit of up to $2,000.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club