Abalone on the Edge

Scientists race to recover an endangered California abalone species

Photo by Liang Xue/iStock

“There are more white abalones in this room than exist in the wild, which is both terrifying and an incredible opportunity,” says Dr. Kristin Aquilino. It’s 6 A.M. on a cool, coastal-California morning in her White Abalone Culture Lab at the UC Davis Marine Laboratory, a large low-slung complex on an ocean bluff in Bodega Bay. Today is spring spawning day for the captive breeding program Aquilino leads, part of a major recovery effort for this endangered species of mollusk.

Aquilino uses a spatula to pop a six-inch adult out of its tank. She then takes a rounded blade to pull its big suction foot away from the edge of its single-domed shell to sex it, inspecting its cone gonad. “Female, three by 313.” An aide takes note. This morning’s potential breeders—mostly nine- and 10-year-olds from earlier in-house spawns, along with a few permit-collected wild animals that can live up to 40 years—are carefully placed in brown plastic trays of seawater on a big-wheeled trolley.

If all goes according to plan, these captive abalones’ offspring will play a crucial role in helping to eventually reestablish self-sustaining abalone populations along the California coast. Much like the state’s wolves and California condors before them, these edible marine snails are facing extinction even as attempts to rebuild their numbers slowly gain momentum after 20 years of effort. The White Abalone Recovery Consortium, led by the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration, involves over a dozen government agencies, marine labs, schools, aquariums, and other nonprofits. Its focus includes wild population surveys, captive breeding, restoration stocking, education, and outreach. Hundreds of people have dedicated hundreds of thousands of hours to the effort over the years at a cost well into the millions over two decades.

Abalones were once ubiquitous in California coastal waters. Shards of abalone shell have been found in 60-million-year-old Pacific rock formations, and their remains have been discovered in 10,000-year-old Native Californian shell mounds. But in the past 150 years, their numbers have been whittled ever downward due to over-harvesting. In the 19th century, Chinese immigrants developed a commercial market for abalone meat and its mother of pearl shell used for buttons. By the 1960s, abalone—pounded, trimmed, and seasoned—was part of the California culinary scene, along with outdoor barbecues, avocados, and oranges. In 1972, commercial divers collected 143,000 pounds of white abalone, the particularly delicious deep-water species. By 1980, approximately 99 percent of white abalones had been fished out, nearly pan-fried to extinction.

Photo courtesy of Natasha Benjamin

In 2001, with maybe a few thousand white abalones left in the wild, it became the first marine invertebrate listed under the Endangered Species Act. The black abalone joined the white species on the ESA list in 2009. Today, all seven species are in trouble as a result of the now-banned (in California) commercial harvest, illegal poaching, a bacteria-based withering disease, and climate-change-linked ocean acidification and loss of kelp forest habitat.

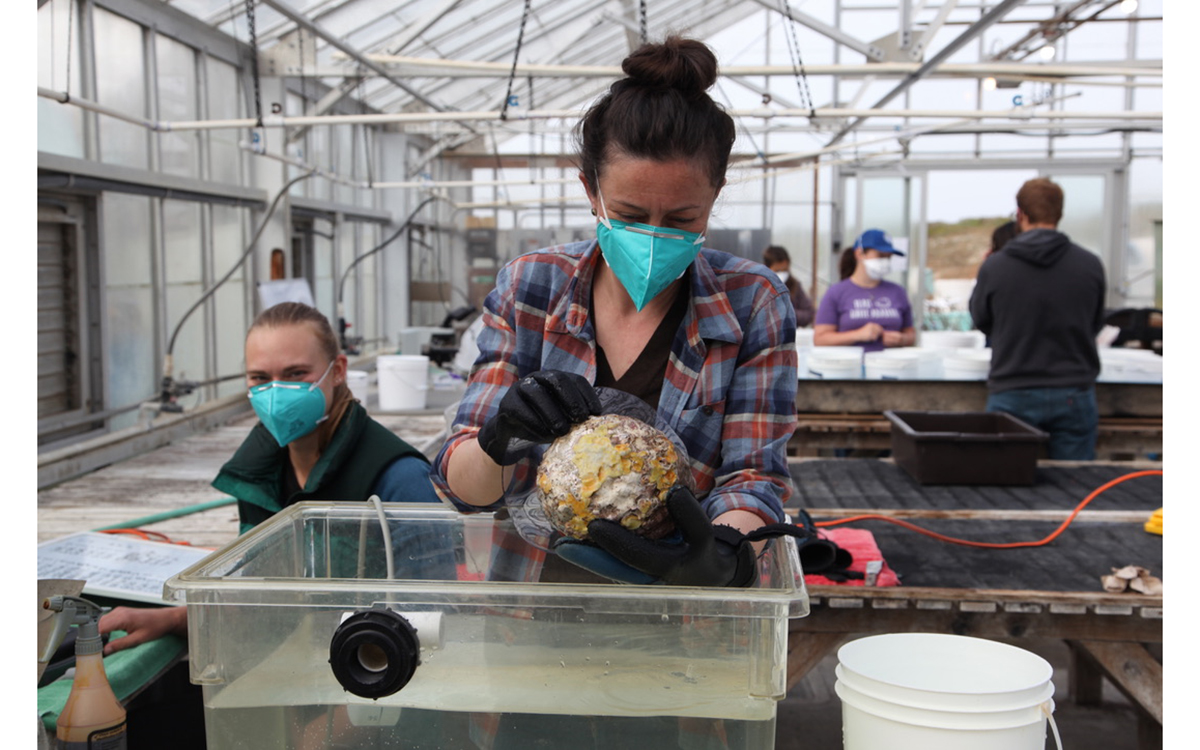

The captive breeding program at Dr. Aquilino’s lab is focused on reversing that decline. Amid the burbling sounds of stacked grow-racks full of thousands of pinhead-to-thumbnail-size one- and two-year-old abalones, a lab technician rolls a trolley outside and over to a greenhouse where three dozen adult animals are put in buckets of seawater with a dash of hydrogen peroxide “love potion.” This will trigger a few of them, five females and one male this time, to spawn and release their eggs and gametes. The eggs form an olive-colored cloud in the water. After a dump and rinse to clear the chemicals out of the buckets, their next emissions will be mixed in plastic pitchers in a nearby cold room, the sperm-to-egg ratio monitored on slide samples under a microscope.

Twenty-four hours later, 5.7 million eggs, 1.2 million of which will develop into larvae, are packed on ice and flown to Southern California by a volunteer pilot from the nonprofit LightHawk aviation conservation group. This is part of what Heather Burdick of the Los Angeles–based Bay Foundation calls “the abalone conveyer belt” for breeding and release. Among the recipients of the fertilized eggs will be the foundation’s “Grand Central Station,” a marine lab at the Port of Los Angeles from which many of the animals grown at other facilities will eventually find their way back into the ocean.

Photo courtesy of David Helvarg

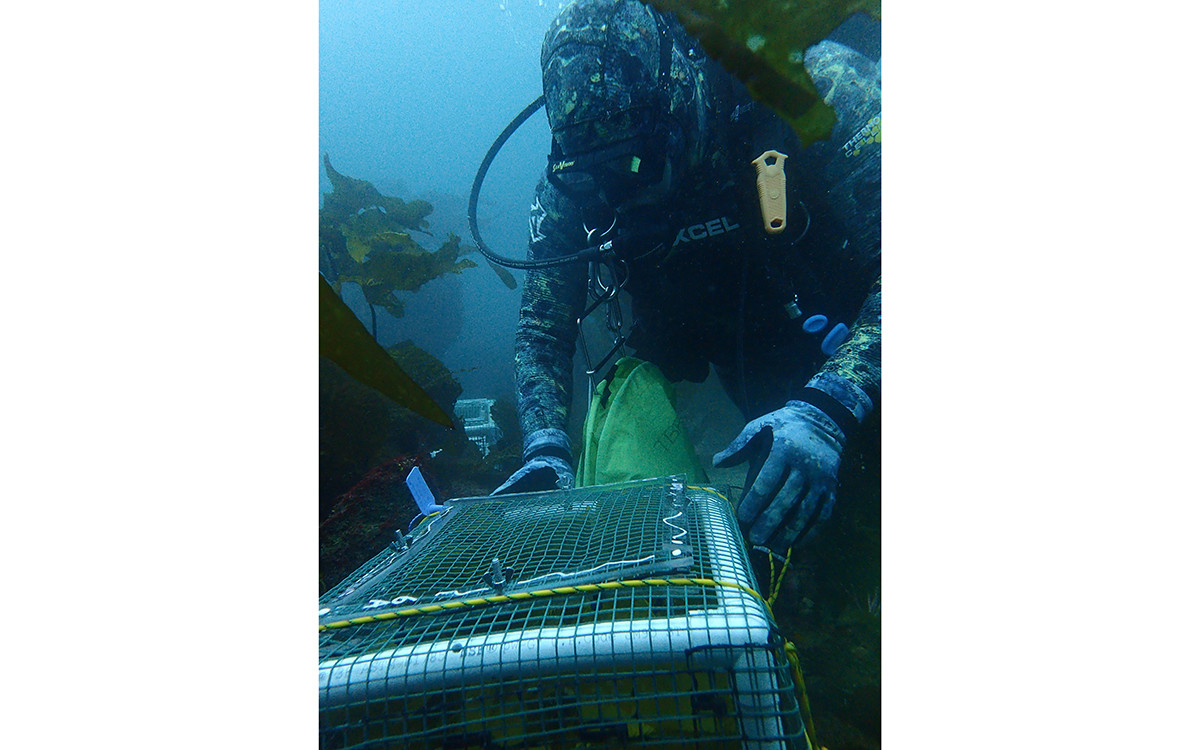

In 2019, after testing wild-release techniques using red abalone surrogates, 1,200 two- to four-year-old white abalones were placed on the ocean floor by divers at semi-secret locations off of Palos Verdes in Los Angeles and kelp beds off of San Diego. In 2020, due to restrictions on government divers and other COVID-related challenges, only about 600 were released. The plan for spring 2021 is to release 1,000 abalones at each of the two locations. Future plans call for planting 10,000 a year at these and additional locations in the hope of restoring the millions of wild animals that were killed off for high-priced dining over the past 50 years.

Other challenges to white abalone restoration include what marine biologists call “concentration”—these “broadcast spawners” only reproduce if they’re within a few feet of each other. Meanwhile, ocean acidification due to runaway carbon dioxide emissions slows the early growth of juveniles, as it does with other shell-forming creatures.

“We’ve fallen in love with these snails, but it takes a lot of effort,” says Burdick. Volunteers and paid urchin divers place the animals on rocky bottoms in special cages and PVC “condos” that they can crawl out of but that initially protects them from predators such as sheepshead, lobster, and octopus. Remote underwater cameras keep an eye out for any uptick in predation around the release sites; so far, none appear to be significant. Since abalones are notoriously hard to spot (they hide among the sea rocks until they grow larger and come to resemble the rocks themselves), it is difficult for marine biologists to do follow-up surveys with divers and robot submarines to evaluate the small abalones’ survival rate. “So it might be years before we know how successful our outplantings have been,” Burdick admits.

Photo courtesy of Bay Foundation

Photo courtesy of David Helvarg

Already, it has taken years to develop an effective breeding program to keep the abalone conveyer belt going. In 1998, a single white female abalone nicknamed Abigail was put in a tank at the University of California, Santa Barbara. The hope was that with her millions of eggs, she could produce brood stock in captivity. Unfortunately, by the time a male, dubbed Abner, was found, Abigail had died.

In 2001, 100,000 juveniles were successfully bred at a research and aquaculture facility next to a power plant in Oxnard, but after water pumped from the plant introduced a bacteria associated with withering syndrome, 95 of the juveniles died. The survivors were dispersed to different facilities, most going to Bodega in 2008, where Jim Moore, a state shellfish pathologist, developed an anti-bacterial bath to treat withering syndrome and a shell rub of beeswax and coconut oil to remove boring worms and sea sponges. “Between the cleansing baths and exfoliating wax treatment, we have the most pampered snails in the world,” Aquilino says with a grin. (Still, despite these precautions, in 2011 a harmful algal bloom hit the local Northern California waters, and the Bodega facility’s pumps, filters, and UV treatments were not enough to keep that year’s successful spawn of white abalones alive.)

At the Bodega greenhouse, Aquilino hands an abalone to another scientist, Dr. Sara Boles, who puts it in a tank and places an ultrasound wand against its muscular, sand-colored foot. The abalone’s internal organs, including its gonads, appear on a laptop screen and are rated one to five for a breeding evaluation. Also visible is the slow-beating heart of this endangered animal. According to UNESCO, without significant change, more than half the world’s marine species may face extinction by the end of this century.

“It’s a hell of a lot easier to conserve them in the first place than to bring them back from the brink of extinction,” Aquilino says.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club