The Best (and the Weirdest) Nature Films From Sundance

Three nature films to look out for in 2022

I love nature films. Not just the ones that show up on the major streaming platforms, but also the deeply strange and specific ones that used to just make a few rounds at film festivals and then disappear, to be found only maybe (if you’re lucky) within university archives, or a well-stocked public library.

These days, streaming services like Kanopy and Mubi sometimes take on films that aren’t mainstream enough to wind up on the larger platforms like HBO or Netflix. (One of my favorite environmental films of last year, Taming the Garden, is now on Mubi.) But they’re not always well promoted on those platforms, so you generally have to know what you’re looking for in order to find films like these.

With that in mind, these are the environmental gems I saw at Sundance that I recommend keeping an eye out for this year. A few have already been picked up by distributors, and others will likely show up at other film festivals this year, where odds are high that you can buy a ticket or a pass to stream them in today's pandemic-adapted film festival circuit.

Fire of Love

Directed by Sara Dosa

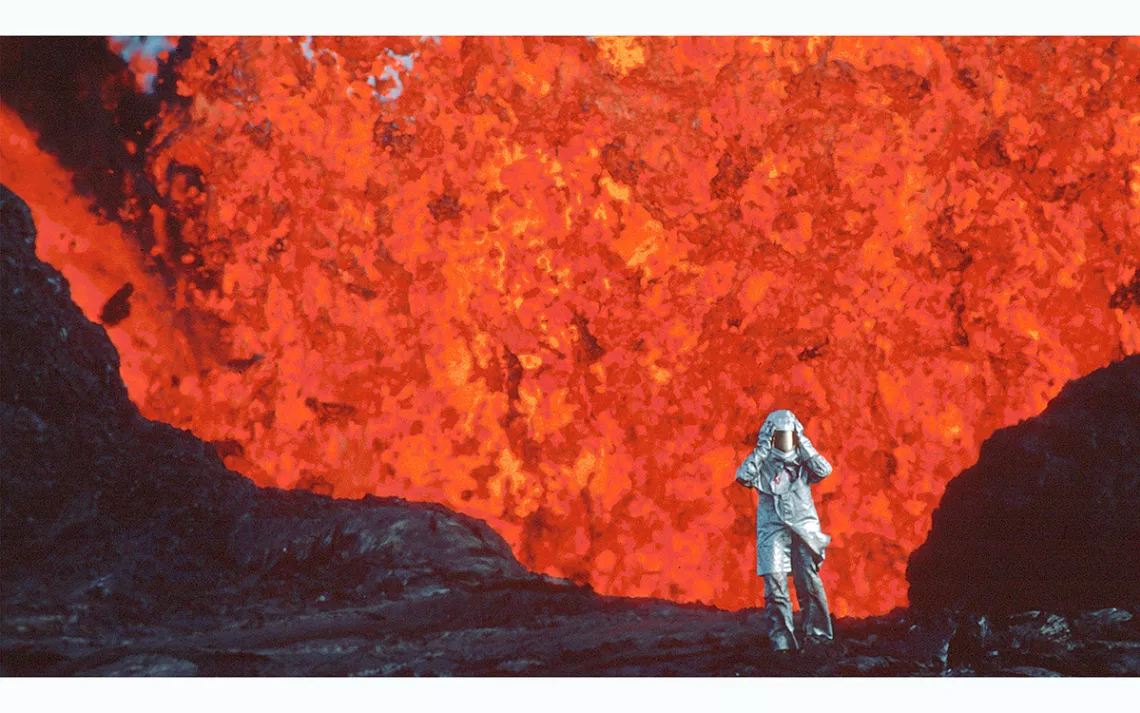

Wes Anderson has so successfully replicated the vibe of 1960s French nature documentaries that it’s hard to watch Fire of Love—a real documentary about real French volcanologists—without expecting Gwyneth Paltrow in a fur coat to show up and languidly smoke a cigarette. In Fire of Love, married scientists Katia and Maurice Krafft really do wear jaunty red ski caps when they aren’t tottering around volcanic craters in their own homemade metal safety suits (which make them look like the love children of a Moomin and a foil-wrapped baked potato), clumsily making “snowballs” out of hot volcanic rock. The documentary was acquired by National Geographic during the early days of the festival, so clearly the eccentricities weren’t a drawback.

The Kraffts pose unabashedly for the camera, cook an omelet at the edge of a crater, and announce implausible plans to surf hot lava down the side of a volcano (well, just Maurice that time—Katia is more sensible) and actually do go sailing in a lake of sulfuric acid (again, a Maurice notion that does not go well).

Publicity materials for the film are not shy about the fact that both Kraffts died in a volcano-related incident. The only real suspense watching the film is guessing which volcano is the culprit, and anxiety mounts as the story progresses. Still, the Kraffts clearly lived life to the fullest, doing what they loved. “If I could eat rocks,” says Maurice, at one point, “I would stay on the volcano and never come down.”

All That Breathes

Directed by Shaunak Sen

Mohammed Saud and Nadeem Shahzadas found their first injured black kite—that’s a predatory bird commonly found in Delhi—when they were bodybuilding-obsessed teenagers. They took it to the Jain-run Delhi Bird Hospital, which rejected it, on the grounds that the bird wasn’t vegetarian—so they taught themselves how to bandage injured birds, using bodybuilding magazines like Muscle Flex as anatomical reference.

By the time filmmaker Shaunak Sen comes along and begins filming them, Saud and Shahzadas have spent nearly two decades operating a full-on, gritty, donation-funded kite clinic in the same small warehouse where they run the family soap dispenser business. Anyone who has spent time around animal rescue people will recognize the types involved—especially Saud, who is the kind to strip down to swim trunks and swim out to capture an injured bird spotted by a local fishermen, without entirely knowing that he has the strength to swim back (he doesn’t, and he another bird rescue volunteer ultimately need to be rescued by an extremely grouchy Shahzadas).

Just as extreme burnout looms, financial reinforcements come in the form of donations, inspired by an article about the clinic in The New York Times. But even after getting the funds to build a full-on, dedicated kite hospital, the small crew continues to struggle as the number of injured kites continues to rise. The film is weirdly vague about the reason—while the brothers often discuss air pollution (which admittedly, is not great for birds, or anyone else living in Delhi), articles about the clinic describe its main work as treating injuries caused by the glass-covered kite strings used in Delhi’s competitive kite fighting matches. (Just to be clear, those fights involve the kids’ toy kind of “kites”—avian injuries are caused when “kites” the species accidentally collide with them while in flight.)

That aversion to specifics appears to be a deliberate artistic choice—while there’s no shortage of cute shots of predatory birds glowering away in the corner of the soap dispenser shop, and perfectly composed footage of urban wildlife, the real focus of the documentary lies not on the animals themselves, but the emotional ups and downs of running a wildlife clinic on a shoestring budget. “I’ve been so happy that even if my wife starts to pick a fight, I just start singing, and smoothly avoid all fights,” says Shahzadas, after a successful fundraising round. Anyone who has been involved in a hopelessly underfunded cause can relate.

32 Sounds

Directed by Sam Green

This wide-ranging documentary/live performance hybrid on the subject of sound is not overtly about nature. However, recordings of extinct animals at the British Library’s sound archives, foghorns, and Joanna Fang, a foley artist who can make the sound of a tree falling in a forest better than the tree can, all play a role—to the point where 32 Sounds begins to feel like more like a celebration of nature and being in the world than most self-proclaimed nature films.

32 Sounds has, admittedly, a lot of ground to cover sound-wise, but it keeps returning to Annea Lockwood, an elegant experimental composer who once performed compositions made entirely of her standing in a corner, breaking sheets of glass. Later in her career, Lockwood began to record the sounds of different rivers with an underwater microphone, and now lives in the countryside, mostly listening to the sounds of insects at dusk (or “listening with” as she insists on calling it). Lockwood has the quiet charisma of someone who could have easily become a cult leader if she had decided to take that path, and her discussion of sound is enough to make you want to wander through grass forever.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club