Black American Bus Drivers At Risk

Public transportation needs to be reliable, safe, and green

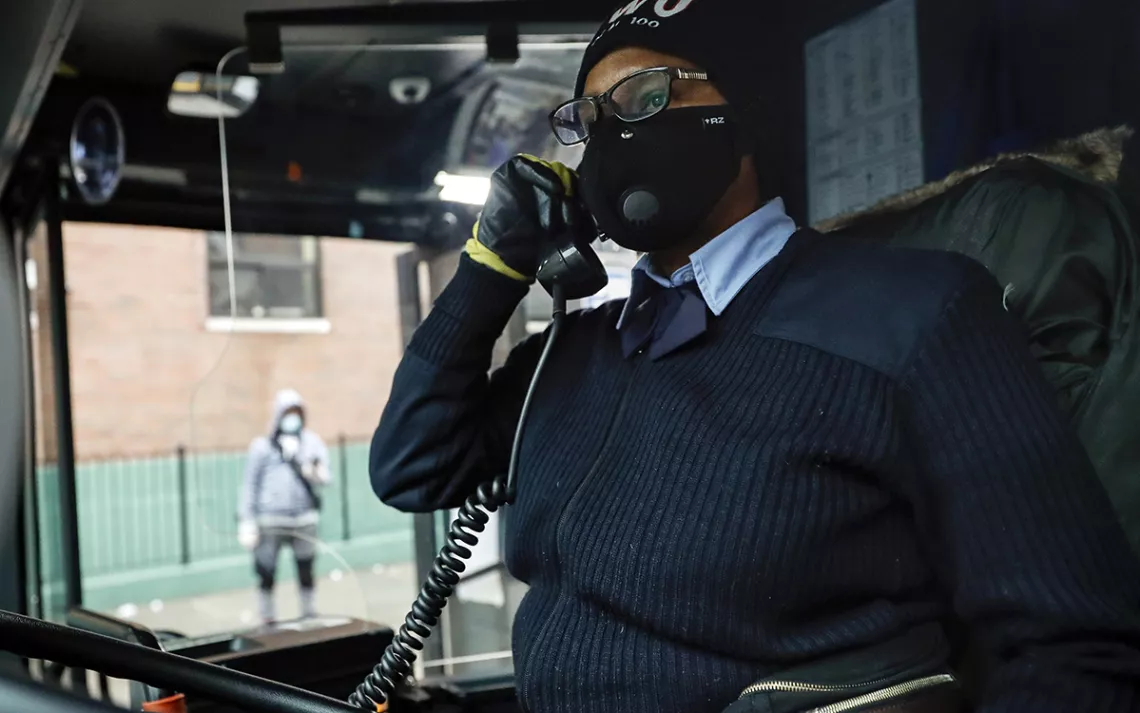

MTA bus driver Denise Watkins wears personal protective equipment as the bus operates without fees on April 24, 2020. | Photo by AP Photo/John Minchillo

Eleven days after posting a video demanding better protections for service workers who are on the front lines of the pandemic, Jason Hargrove, a 50-year-old bus driver in Detroit, Michigan, passed away from COVID-19. In the early days of the pandemic, city officials were slow to meet transit workers' demands for personal protective equipment. Glenn Tolbert, president of Amalgamated Transit Union Local 26, says that even before Hargrove passed, it took bus drivers refusing to work for Detroit to implement adequate safety precautions.

“Now, passengers enter through the back door, so there’s less contact,” Tolbert said. “They waived fares for riders and have provided bus drivers with masks, gloves, and disinfectant wipes.” Nevertheless, Tolbert himself is now infected with COVID-19.

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has exposed many egregious flaws in US society—perhaps most glaringly, the enormous health disparity between black and white Americans. Data from Michigan reveals that while black people make up 15 percent of the population, they account for 35 percent of diagnosed cases of COVID-19 and 40 percent of deaths. According to a report from WBEZ Chicago, black Americans account for 70 percent of COVID-19 deaths in the city.

Similar to other races, the majority of black people who have passed from COVID-19 had underlying health conditions such as high blood pressure, respiratory illnesses, and cardiovascular disease. In early April, Surgeon General Jerome Adams issued a statement warning black Americans that they were at increased risk for COVID-19 due to the underlying health issues that disproportionately plague their communities. Many in those communities were upset about the statement, interpreting it as an insinuation that African Americans were responsible for their health disparities compared with other races and a reinforcement of the notion that oppressed communities are culpable for their own suffering.

But what Adams was describing is actually the result of systemic redlining, exposure to environmental pollutants, and an inability to social distance due to a heavy reliance on public transportation.

Black Americans make up nearly 30 percent of US bus drivers and essential workers (including food service workers, postal service workers, custodians, and delivery personnel) and over 30 percent of nurses and health aides. This puts them, their families, and the elderly they work with at higher risk for COVID-19 exposure. Most essential workers rely on public transportation: Black Americans make up a quarter of all public transit users. While certain concessions have been made during the pandemic—waived fares, masks for transit workers—earlier implementation of sanitation and distancing measures could have curbed many potentially avoidable deaths.

In Maryland, black people compose 30 percent of the population and 40 percent of COVID-19 deaths. In Montgomery County alone, COVID-19 cases have surpassed 2,000. Clint Sobratti, a Ride On bus driver, says that recent changes have improved the quality of ridership, including route adjustments so buses pass by hospitals and grocery stores more frequently.

The situation in New York probably sheds the most light on racialized transit inequity. Forty percent of MTA workers identify as black, and 22 percent are 55 to 62 years old, creating a dangerous cocktail for exposure risk. Nearly 60 MTA bus and subway workers have died from COVID-19, and while the MTA has agreed to pay $500,000 to the families who have lost a loved one, many still believe that protections were not put in place fast enough.

“The challenge is in how to organize,” Miranda Nelson, the New York director of Jobs to Move America said. “One priority is making sure transit agencies have the resources they need to cope with the virus, and that transit workers have on-the-job protections that they deserve.”

In March, the federal government provided $25 billion in stimulus funds to ease burdens on public transportation in major cities, but New York/Newark, New Jersey, which carries 40 percent of the country’s public transit ridership, was awarded only $5.44 billion due to federal restrictions on how much MTA can receive in federal funding.

“New York is the epicenter of the crisis, and it feels like the federal government is leaving New York to cope with these issues on its own,” said Danny Pearlstein, policy and communications director of NY Riders Alliance. “Many of the people who use public transit power the city’s pandemic response even though they are uniquely vulnerable.”

Pearlstein recognizes that the COVID-19 pandemic has created an air of distrust of public transportation. Amid acrimony over the city’s slow implementation of stringent sanitation for public transit systems, MTA workers have increasingly been calling in sick. That has led in turn to increased crowding in trains and buses, even though overall ridership is down.

“We have to deliver for the communities of color who delivered for us and continue to deliver for us during the pandemic,” Pearlstein said. “The people most dependent on the MTA system are those who are cut out from the wealth coming in from the city and the government.”

Organizing toward better transit conditions is linked to the necessity for greener transportation. Due to shelter-at-home restrictions, pollution has plummeted dramatically, but essential workers are still at risk for exposure to pollutants.

The NY Riders Alliance has called for the purchase of 500 new electric buses to be deployed as soon as possible. Jobs to Move America has a similar vision, specifically requesting that these green buses be placed in communities that are most vulnerable to air pollution exposure and thus at higher risk for COVID-19 complications. “We’re working towards a Green New Normal," said Pearlstein. "We miss going to restaurants and bars; we don’t miss breathing dirty air.”

“This pandemic has made it really clear we aren’t prepared for this crisis, just as we aren’t prepared for the climate crisis,” Nelson said. “We need to invest and expand in green buses as a solution to improving air quality conditions in vulnerable areas. Public transit is a huge factor in combating this crisis and the ongoing climate crisis that disproportionately affects black and brown people. We have a vision for greener transit that will not only improve quality of life but will also provide sustainable jobs for our communities.”

Black Americans tend to live in densely populated areas with increased proximity to industrial facilities, and closing streets to car traffic could potentially alleviate some of the unequal allocation of open space. However, since so many essential workers commute long distances to work, the future of public transit remains uncertain.

“This is a pivotal moment for public transit,” Pearlstein said. “Transit is going to face a very rough road to recovery, but we owe it to essential workers that there is safe, reliable frequent transit service.”

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club