Brett Kavanaugh Is the Perfect Fit for Trump’s Anti-Environment Agenda

Kavanaugh’s environmental philosophy is industry above all else

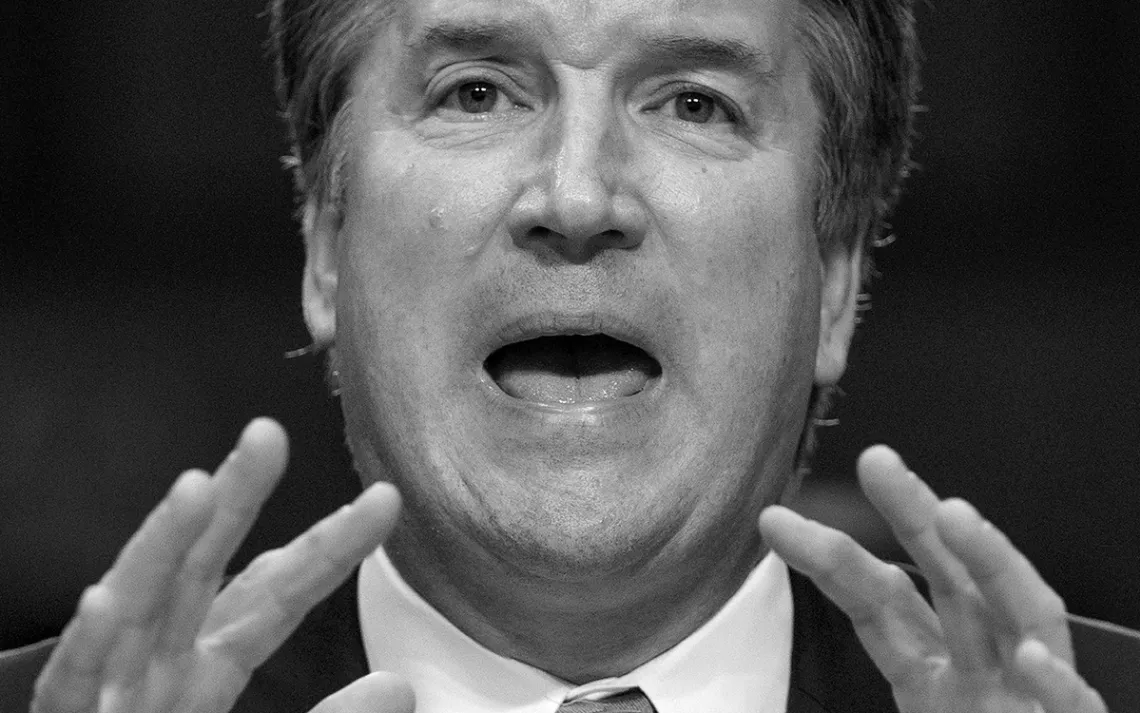

Photo by AP Photo/Andrew Harnik

In 2008, Judge Brett Kavanaugh—while sitting on a panel with two other Republican-appointed judges for the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia—wrote a dissent in which he defended the Bush administration EPA’s attempt to weaken monitoring requirements for polluting industries under the Clean Air Act. Breaking with the majority, Kavanaugh argued that the Clean Air Act gave the EPA all the authority it needed to decide whether states can impose stricter monitoring requirements on certain sources of pollution. In this case, Kavanaugh said, the law made it clear: The EPA was the supreme authority.

But just four years later, writing as part of the majority opinion that struck down an EPA regulation seeking to place limits on sources of downwind pollution, Kavanaugh seemed to have a very different view of the EPA’s authority to regulate air pollution.

“Congress did not authorize EPA to simply adopt limits on emissions as EPA deemed reasonable,” wrote Kavanaugh, who is President Trump’s choice to replace Justice Anthony Kennedy on the high court. “Rather, Congress set up a federalism-based system of air pollution control.”

Environmental cases that reach the federal appeals courts often involve knotty, complicated issues that are highly fact-dependent, and the facts of the two cases cited above are certainly distinct in many ways. But the most noticeable differences of those cases are the ideological perspective of the cases’ petitioners. The 2008 case, in which Kavanaugh affirmed the EPA’s rights to overrule states, was brought by the Sierra Club; the 2012 case, in which Kavanaugh overruled the EPA’s authority, was brought by a utility that owns three coal-fired power plants.

That apparent bias is part of a larger pattern with Kavanaugh. In his 12 years as a federal judge, Kavanaugh has heard 26 cases involving the EPA. He issued some kind of record—an opinion, concurrence, or dissent—in 18 of those cases. In 11 cases, he sided with industry plaintiffs. He sided against industry only twice, and he has never once sided with a public interest group.

“When in doubt, Kavanaugh is inclined to find that agencies are powerless to address pollution or that citizen groups have no power to go into court to enforce those rules,” says Sanjay Narayan, managing attorney for the Sierra Club's Environmental Law Program.

Kavanaugh (who in recent days has been the subject of a sexual assault allegation) has shown a great deal of judicial flexibility in reaching decisions that support industry and criticize regulations. Take, for instance, his dissent in Mingo Logan Coal Co. v. Environmental Protection Agency, a 2016 case that dealt with the EPA’s denial of a permit to a mountaintop-removal coal mining company that sought to dump its waste into West Virginia waterways. Although the EPA found that the dumping would literally “destroy” streams and wildlife habitat, Kavanaugh argued that the agency hadn’t focused on the real costs of the permit denial: the impact on stock prices that denying the permit could have.

But Kavanaugh isn’t always so strict with his requirement that parties consider all the costs when bringing lawsuits. In Grocery Manufacturers Association v. EPA, Kavanaugh dissented from a majority opinion that denied industry plaintiffs’ standing on the grounds that they hadn’t demonstrated a link between the agency’s action and harm to the group’s members. Kavanaugh argued that the industry group should be able to bring their claim to court—even if they hadn’t been able to quantify any harm that they would suffer under the EPA’s rule.

Contrast that dissent with Kavanaugh’s opinion in Communities for a Better Environment v. EPA, a case that denied standing to a public interest group seeking to compel the EPA to create stricter regulations for carbon monoxide. Writing for the court, Kavanaugh found that the petitioners lacked standing because they could not show any link between the alleged harm—namely, that air pollution would negatively impact birds—and the proposed action.

Like the Trump administration, which extols federalism when it helps curtail environmental regulations and shuns it when it leads to limits on pollution, Kavanaugh isn’t an ideologue. His arguments don’t reveal any particular animosity toward the EPA; nor do they show a consistent treatment of fundamental legal principles like standing, or important administrative procedures like cost-benefit analyses. Instead, his ideology is one that often sacrifices legal reasoning at the altar of industry profit. The Trump administration will someday come to an end. But if Kavanaugh is confirmed, his lifetime appointment to the Supreme Court means that the central doctrine of Trumpism—profits over public health and environmental protection—will live on for decades.

If Kavanaugh were to be confirmed to the Supreme Court, he could easily use his position to bar public interest groups from bringing their cases to the high court. Take, for instance, the lawsuit against the federal government brought by 21 youth plaintiffs. Plaintiffs in the Our Children’s Trust case spent months arguing that they had suffered enough direct damages from climate change to have standing—a claim that the federal government has repeatedly appealed. The government has lost each of those appeals, but if the case were to make it to the Supreme Court, it’s an open question whether Kavanaugh would be sympathetic to the plaintiff’s claims. Likewise, look at ExxonMobil’s recent appeal to the Supreme Court to stop an investigation by the Massachusetts attorney general into whether the company knowingly misled shareholders about the risks of climate change. Were the court to agree to hear the case, it’s possible that Kavanaugh would use it as a chance to try to limit the jurisdiction that attorneys general have over multinational corporations like ExxonMobil.

Alternatively, a Supreme Court Justice Kavanaugh could use his power to open up the courts to industry, even in cases where a causal link between regulation and harm is tenuous at best. And as a Supreme Court justice, Kavanaugh could use his position to wave aside the need for cost-benefit analyses—at least, for certain kinds of costs or benefits—in crucial environmental regulation. The Trump administration has already tried to repeal the Waters of the United States rule based on cost-benefit analysis that ignores the economic benefits of wetlands. Economists and legal scholars have characterized those calculations as “illogical” and potentially illegal. But Kavanaugh has already shown a propensity for overlooking cost-benefit analyses when it benefits industry—and repealing the Clean Water Rule is certainly a major goal for both the Trump administration and industry.

As a jurist, Kavanaugh has proven himself to at least be constant in his inconsistency: He rules in favor of industry interests and deregulation, no matter what kind of legal slight-of-hand it takes to get there. His ideological flexibility makes him the perfect reflection of the Trump administration—and a serious threat to the planet for decades to come.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club