Cli-Fi Maven Jeff VanderMeer Talks About His Latest Novel

The “Dead Astronauts” author makes art out of climate collapse

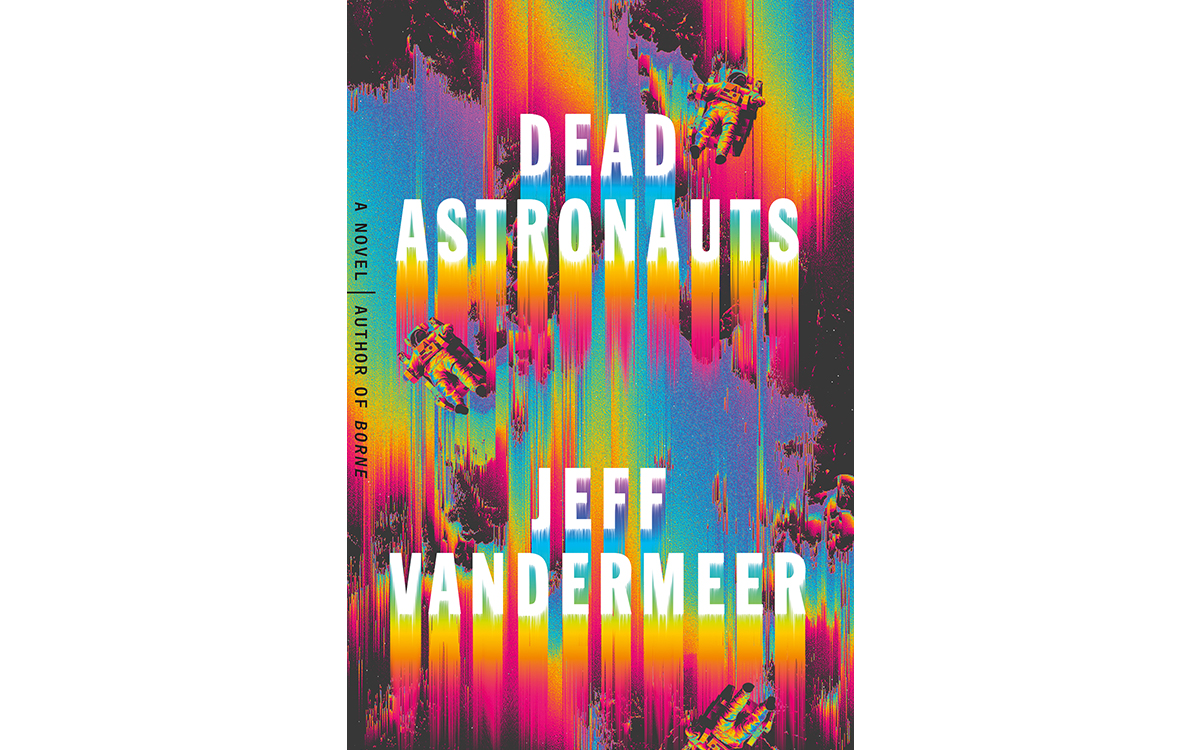

Photos courtesy of MCD Books

More authors are writing fiction about climate change than ever before, but few approach the subject with such intensity, inventiveness, and absurdity as Jeff VanderMeer. Prolific and versatile, the Florida writer has built a career on taking the tropes of science fiction, fantasy, and horror—including time travel, alternate dimensions, and biotech run amok—and twisting them into strange and compelling narratives that often extend beyond those genres’ confines.

The New Yorker has dubbed VanderMeer, who spends a lot of time exploring the wildlands near his Tallahassee home, the "Weird Thoreau.” But this author is no recluse—he's frequently out speaking about climate issues at places like MIT and the Guggenheim, or traveling to promote his books.

With his wife, Ann, an award-winning editor in her own right, VanderMeer has assembled far-reaching science fiction and fantasy story collections, including The Weird, The Big Book of Classic Fantasy, and The Big Book of Science Fiction. The VanderMeers’ second Big Book of Classic Fantasy, covering 1945 to 2010, comes in July 2020.

After publishing experimental stories and novels over the course of two decades, VanderMeer's career shifted into high gear with the 2014 publication of the Nebula Award–winning Annihilation. Adapted for the screen by Alex Garland, Annihilation was the first volume of the Southern Reach trilogy, a critical and popular success published over the course of a single year.

VanderMeer followed the trilogy with Borne, a touching, unsettling novel set in an ecologically devastated “City” ravaged by the pollutants of the “Company,” wherein a young couple looks after a mysterious life form that learns to speak and assert its own identity.

His new novel, Dead Astronauts, out yesterday from MCD Books, is set partly in the world of Borne. Three characters start off on a quest to destroy the Company that brought so much pain and suffering to that world. Their trek involves a giant oracular fox, a mother and daughter haunted by demons, and a centuries-old giant fish. It's a much more compressed and intense read than Borne, full of stylistic and temporal tricks—a puzzle that may confound some readers on their first attempt.

His new novel, Dead Astronauts, out yesterday from MCD Books, is set partly in the world of Borne. Three characters start off on a quest to destroy the Company that brought so much pain and suffering to that world. Their trek involves a giant oracular fox, a mother and daughter haunted by demons, and a centuries-old giant fish. It's a much more compressed and intense read than Borne, full of stylistic and temporal tricks—a puzzle that may confound some readers on their first attempt.

Sierra spoke with VanderMeer, just prior to his Dead Astronauts publicity tour, about the evolution of climate fiction, his sources of writing inspiration, and biodiversity in his native Florida.

***

Sierra: How do you feel about being the “Weird Thoreau,” and how is Dead Astronauts consistent with that moniker?

Jeff VanderMeer: I am actually very thankful to The New Yorker for that, because it allows me to say, when introduced at events, “I thought that Thoreau was the ‘Weird Thoreau.’” The moniker helps in that the novels tend to be discussed in a more useful and wide context. As for Dead Astronauts, in the sense of continuing a dialogue about our relationship to the world around us, I suppose it’s apt enough. But the influences on the novel are multitudinous.

How does Dead Astronauts mesh with your personal feelings about conservation?

What was really important to me was trying to explore the nonhuman and make sure there were at least some nonhuman characters that were not [conveying] views I would call propaganda. Pop culture sometimes makes animals complicit in their own usage by humans, like logos for a butcher shop can make the animal complicit in its own death. I think about things we don’t recognize as propaganda, but it really is when it comes to the nonhuman world.

How did Dead Astronauts evolve? Was it conceived while you wrote Borne?

No. It came out of Borne, but it wasn’t something I was planning until later, after Borne was published and I was thinking about it more. [There] was a fairly powerful image of dead astronauts mysteriously deposited in a courtyard in Borne—I think my subconscious started thinking first about who were they? What was their story? At some point, I thought, well, what is a dead astronaut? What does that actually mean? In a sense, the title is both literal and figurative and crosses some of the other points of view. At a certain point, the fox, similar to the sacrifice of dogs in the cosmonaut program, is sent on an astronaut mission. That’s literal, but there's the more metaphorical throughout as well.

You have the three astronauts: Grayson, Chen, and Moss. Where did you take your inspiration in creating these characters?

I think the context is what they’ve been created to be in Moss’s case; what they’ve been complicit in, in Chen’s case; and what their initial job was, in Grayson’s case. There’s the dissolution of Grayson's [astronaut] mission. Then the three of them have taken it on to try to change the future—a future of apocalypse, if this predatory capitalist Company can’t be stopped.

They seem to be engaged in a Sisyphean sort of quest. In what ways do their interactions reflect your own views of human existence?

What you’re getting at is about activism. What I find, because we’re in this sort of capitalist system that is so difficult to push back against or get outside of, we tend to gauge our success within it. Our metrics are totally bound up in that same system. One of the themes of the book is how does failure advance the cause that we’re working on? We often define success as so absolute that anything short of it seems like complete failure. But a lot of times in the conservation movement, failure is not necessarily something that doesn’t advance the cause to some degree. We’re so connected that failure is broadcast or mourned over by many people not even in the same place. It has an impact on other people’s fight, how they conceive of pushing back against systems giving us ecological collapse, habitat loss, everything else. I wanted to explore that.

Is there a character you’re particularly fond of?

I like the world-weariness of Grayson because she becomes part of this mission in spite of a certain fatalism. She has to push back against her own cynicism to participate.

Also, the anger of the fox appeals to me. The fox came about [from] talking to a radical environmentalism class at Hobart and William Smith Colleges. They were giving me feedback that they liked novels like Annihilation but wanted a more direct, didactic literature of ecology, the environment, and climate crisis. How do I translate that into fiction, because the whole point of fiction is not to be declarative. It is to be ambiguous and to leave space for the reader to make up their own mind. I came up with the character of the fox because as a revolutionary, there’s a directness that’s central to the character. That makes the didactic part of the narrative seem much more natural, or should, than the author somehow shining out from the narrative to give you a lecture.

Your father is head of the US Department of Agriculture Fire Ant Lab in Gainesville, and your mother is an artist. Can you talk about how your parents' occupations have influenced you?

[They] were really very influential in making me interested in environmental issues, because of my dad studying invasive species. My mom is a painter and was a biological illustrator before computers did away with that job. They joined the Peace Corps, so as a family we lived in Fiji when I was a kid. My dad was studying the predation of the rhinoceros beetle on coconut trees. My mom did both art and biological illustration, a lot of studies of sea turtles. There was a way in which art and science meshed.

Do you see any trends in current science fiction and fantasy that are particularly noteworthy?

Because of the anthologies, I don’t read a lot of science fiction or fantasy for pleasure. I read short stories for the anthologies, and then I read a lot of mainstream fiction. I’ve been really happy about things like [Richard Powers's] The Overstory and others where you see all sorts of climate change issues involved. I’d like to see more of that. We’re really in the middle of it, so climate fiction is not science fiction; it could be any fiction at all. I think science fiction can be as oblivious to environmental issues as any other form of literature, or as aware.

You have said you were deeply affected by the Gulf oil spill. Has there been a similarly traumatizing event since then?

Ron DeSantis, our governor, recently allowed the Florida Department of Environmental Protection to support exploratory oil drilling in the Apalachicola area. There’s just no way they can actually drill for oil there without causing immense environmental damage. He’s also signed this bill about toll roads to nowhere, which would cut across the heart of the last parts of wild Florida and make a wildlife corridor across the state impossible. Even people on the committees to create the route are aghast. Those two things right now are similar. They cause a great deal of stress for anyone who cares about biodiversity, about the number of species in north Florida that are unique here. Those are things preoccupying me, and the kinds of things I’m gearing up to try and do my part to be active about opposing.

Are you able to find optimism in the face of the developments in the past few years?

My daughter is a sustainability consultant who does work for the World Wildlife Fund but also is helping cities, including Charlotte in North Carolina, to become [zero emitters]. She’s doing things; she knows the data [to the point that] she still has hope. I have hope because she is more of an expert on it than I am.

Also, I have seen a lot of people respond to the idea of making as much biodiversity as possible on private property, in reaction to Trump policy, which is environmentally devastating across public land. People are committing to not using herbicides and pesticides and are planting native plants. That could make a real difference. We need to push back as much as possible. I also think people need something in their day-to-day lives to hold onto, and to show that they can do something positive. In this case, it’s so inexpensive; if you have a yard, [it just entails] not mowing grass, not using herbicide, not spending money, not leaf blowing. Small things that add up, even just for migratory birds. It could be really important, and I see more and more people responding to that.

I understand you got some push-back from neighbors and municipal authorities when you let your landscaping go more native. What happened?

That was at the old house, which was good training for the new house. A neighbor complained about our “weeds,” which were native wildflowers. The city inspected and gave us a citation. I responded by weeding the wildflowers into a rectangle shape and putting a little white fence around it. I also weed-wacked the outer fringe of the yard near the road. What I learned is that the signs and symbols of a lawn are sometimes more important than anything else. The neighbor never complained again, and the city never cited us again. The lesson is that the impression of conformity is often enough for some.

You’ve previously donated a percentage of book royalties to environmental causes. Are you planning to donate a percentage of royalties from Dead Astronauts?

At least 20 percent will be donated to the Center for Biological Diversity and to the Friends of the St. Marks Wildlife Refuge [in Florida]. The center’s been aggressive, in partnership with others, in terms of lawsuits [against] Trump’s worst policy changes. The St. Marks Wildlife Refuge is a truly special place. It’s not just because I’m near it. In terms of biodiversity and the number of different kinds of microclimates in it, it truly is unique [and] needs to be as protected as possible.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club