What Are They Teaching Kids These Days?

Increasingly, comprehensive environmental education is starting in high school

Balboa High School students take part in their institution's Wilderness Arts and Literacy Collaborative. | Courtesy of WALC

Conrad Benedicto, an English and social studies teacher at Balboa High School in San Francisco, admits that his desire to launch the Wilderness Arts and Literacy Collaborative was born partly out of selfishness. “The teachers who founded WALC really just wanted to figure out how we could not be in the classroom,” he says.

If teachers feel stifled in the classroom, surely students must, too. And that translates into lower test scores and more dropouts—continuous problems for Balboa High, which was cited in a 2000 class-action lawsuit the ACLU filed against the California Board of Education for allowing substandard conditions in schools that primarily serve low-income students of color.

Prior to that, the San Francisco Unified School District, frustrated with low test scores and poor conditions, had already fired Balboa’s entire staff in 1996. The new faculty then implemented small-learning communities, in which groups of students are linked via a core group of classes focused around a central theme, somewhat like a college major. In 1999, Benedicto and several colleagues founded WALC, which uses hands-on environmental education as a unifying theme to facilitate teaching subjects such as history and English.

The educators may not have realized it at the time, but they were pioneering a trend in California and perhaps throughout the nation: comprehensive environmental high school curricula. While outdoor education is certainly nothing new, WALC was novel in that it used the natural sciences as a framework to tackle problems in other classes, providing students with an interdisciplinary understanding of how humans interact with the environment. This schools-within-a-school model is an increasingly popular technique for teaching environmental studies in high school.

WALC students at Balboa take part in monthly habitat restoration field trips, and also attend up to three camping excursions and three day-long trips each year. “For example, we go to Lassen Volcanic National Park and we look at tectonic and gradational forces as the two things that shape the landscape,” Benedicto says. “Tectonic and gradational forces then become a really effective metaphor to understand supply and demand, for example, and the way supply and demand, in our capitalist system, determines price and quantity.”

Another trip takes WALC students to Lake Tahoe, where Benedicto says swimming and hiking allow them to develop a connection to the place—which makes them more excited to learn about lake ecology and the physics of lake turnover. Not only do the kids get a lesson in conservation and politics (learning about pollution, and about policies that can help preserve the lake’s ecosystem), but they continue to explore their sense of place through history lessons and novels, by analyzing how alienation can motivate behavior.

WALC students in their outdoor classroom. | Courtesy of Balboa High School

WALC students at Balboa also complete an environmental legacy project to improve their community. For instance, several years ago some students discovered through a survey that the school’s urinals—which consume less water than toilets—weren’t being used because they lacked dividers. So, WALC students fundraised and campaigned for the school to install dividers and convert the urinals to low-flush.

WALC teachers make it a priority to develop curriculum that’s relevant to Balboa’s specific student body. “What really really mattered to us was underserved students, students of color, and [the question of] how can we serve them better,” Benedicto says. “And nature was the way that we discovered to do what we wanted to do.”

The program proved so successful at Balboa that a second, similar one opened at Downtown High School, a continuation school in San Francisco for students at risk of not graduating. At Balboa, WALC students are more likely to be accepted to schools such as those in the University of California system and attend college, compared to the rest of the student body. At Downtown High, the WALC program has increased attendance rates.

Across the Golden Gate Bridge, students in the Marin County suburb of San Rafael also have the opportunity to participate in comprehensive environmental curriculum at the Marin School of Environmental Leadership. Like WALC, MarinSEL is a small-learning community within Terra Linda High School that integrates environmental learning into core classes like English, geography, and health. But while WALC highlights outdoor experiential lessons, MarinSEL is a career-focused, project-based program.

Expectations are high for MarinSEL students—beginning fall semester of their freshman year, they tackle environmental projects with community partners. These require skills in public speaking and professional interactions, and sometimes even grant-writing and event-planning. Recent projects have had high school students securing funding for an electric vehicle charging station at Point Reyes National Seashore, developing a sustainability plan for the San Rafael Airport, and installing natural water-filtration islands in a local lagoon. Students also build chicken coops in an environmental engineering class and, during their junior year, launch sustainable businesses.

Rising sophomore Eleanor Huang applied to MarinSEL because she sought an education that would explore how to live in a world adapting to climate change. “It’s kind of scary to imagine our beautiful Earth slowly crumbling because of the systems that we’ve built,” she says. “But MarinSEL also does a really good job of giving us different ways to use our own voices and our own imagination and ideas to actually come up with ways to solve the problems.”

While MarinSEL’s founder Cyane Dandridge truly believes in the public school system, she thinks it needs “some injection of innovation and novelty” to better teach kids how to deal with climate change and other environmental issues. That’s why she loves the school-within-a-school system: it allows students to participate in the campus community while providing an alternative to traditional learning.

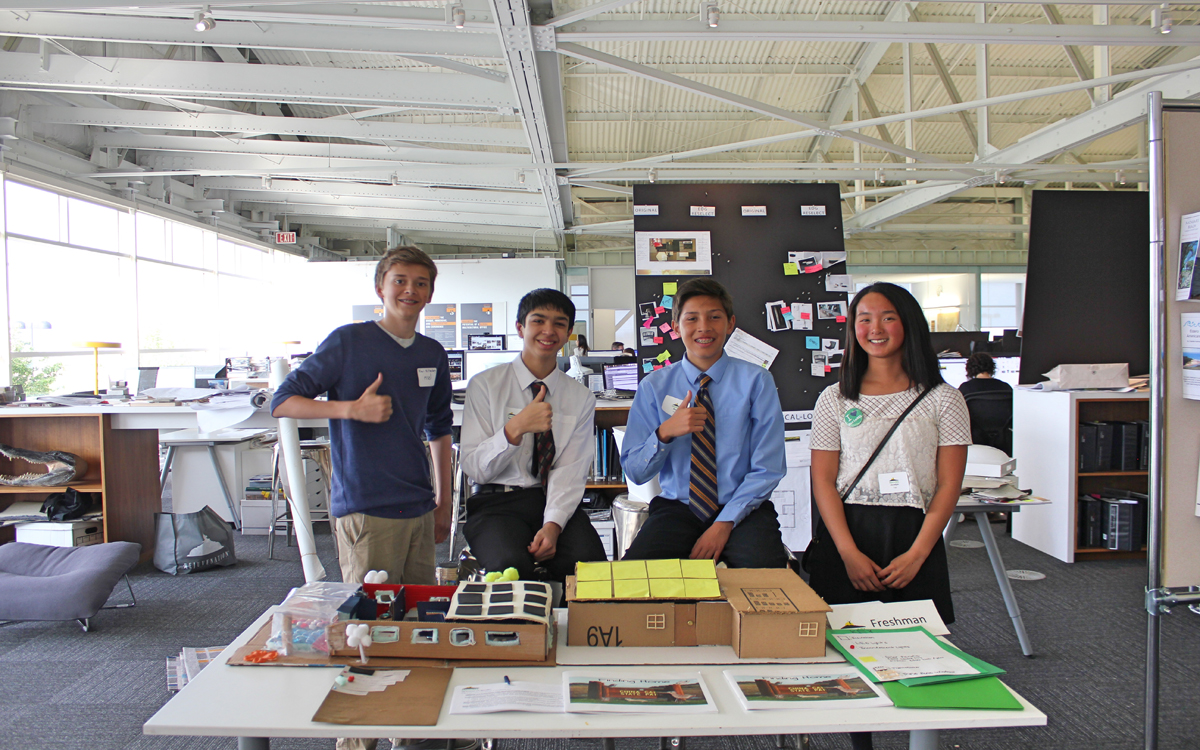

These MarinSEL students are developing a zero-net-energy home. | Courtesy of MarinSEL

The School of Environmental Leadership is able to accomplish all this thanks in part to an external board of dedicated directors and support staff—which WALC lacks. The board is aiming to open two more programs in area high schools in 2018, with more likely to follow.

“We’re not going to be able to address these issues through traditional means, through just slapping up solar panels or even looking deeply at energy efficiency,” Dandridge says. “We need innovation, and the only way that we’re going to get innovation is to teach people to think differently and to approach problems differently.”

Dandridge runs another nonprofit called Strategic Energy Innovations, which develops environmental curricula and teacher trainings for public schools. She says demand for these services has soared in recent years, particularly as schools and employers realize how many jobs are available in the environmental sector.

“And that’s exciting,” Dandridge says. “These schools-within-a-school are interesting, but what I love is there’s more and more uptake on just integrating these aspects into traditional education so that every student is getting them."

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club