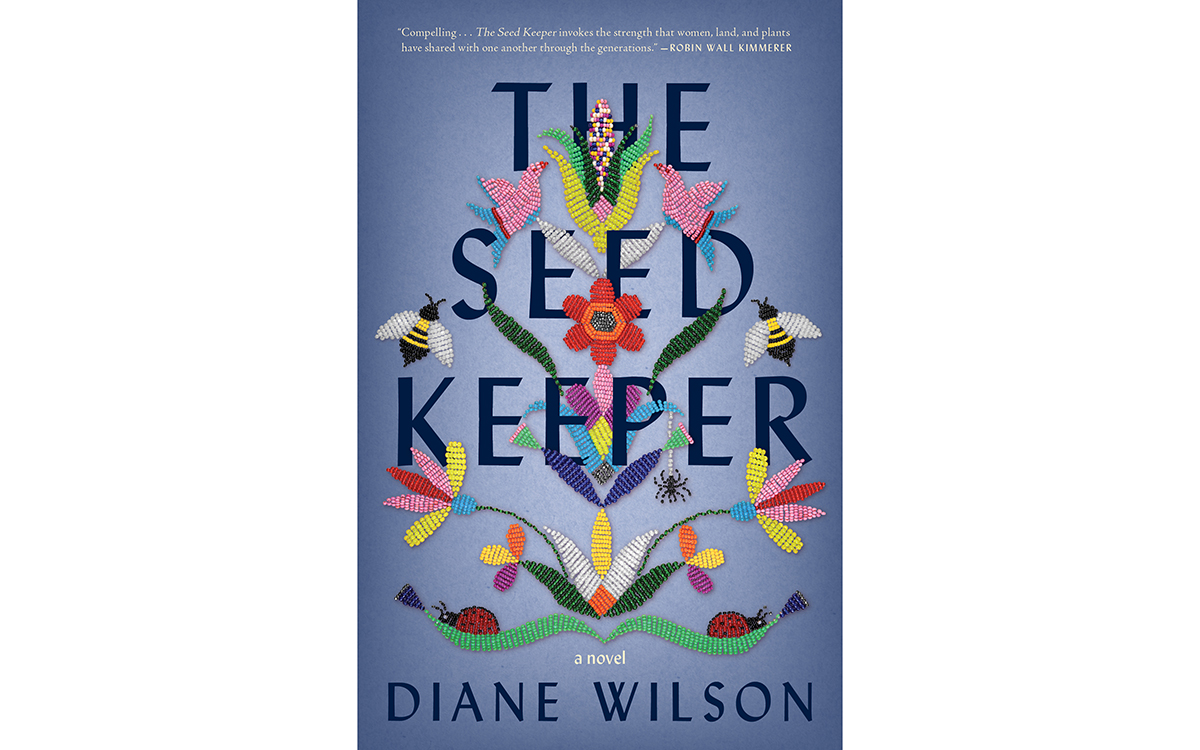

Diane Wilson on Seeds and the Stories They Tell

For the author and activist, seeds are the key to survival

Photo courtesy of Sarah Whiting

Marie Blackbird, a young woman, and her family are on the verge of being rounded up by soldiers and sent to Crow Creek Reservation. It’s the immediate aftermath of the Dakota War of 1862, and the Dakota have been expelled from Minnesota. Marie and her mother hastily sew seeds into their skirts and hide them in small pouches to carry on the long trek to South Dakota.

This scene from Diane Wilson’s novel The Seed Keeper—out this month from Milkweed Editions—is the stuff of fiction, but it’s inspired by real events. In 2002, Wilson participated in the first annual Dakota Commemorative March to honor the Dakota who were forced to walk 150 miles from the Lower Sioux reservation to a prison camp at Fort Snelling. During the march, she heard stories of Indigenous women saving life-giving seeds in the midst of upheaval and hardship.

“I thought about how strong and committed they had to be to future generations to protect those seeds during such a difficult time,” Wilson told Sierra.

Wilson’s participation in the commemorative march was part of a years-long effort to understand her own family history. Her great-great-grandmother Rosalie Marpiya Mase was a Dakota woman who married a French-Canadian trader. When the Dakota War broke out, they and their seven children took refuge with white settlers at Fort Ridley. Their eldest son fought to defend the fort against Dakota warriors.

After researching her family’s complicated past, Wilson wrote her first book, Spirit Car, in 2006. In the memoir, she calls the Dakota War of 1862 “an epochal event for Dakota people and the state of Minnesota, whose consequences continue to ripple through our lives.”

While she was still piecing together her family’s story, Wilson took up what she calls seed work—finding and growing Indigenous heritage seeds. It was part of a broad communal awakening. “People were just beginning to come back to this work of gardening and growing seeds,” a process that she compares to the act of remembering. As the movement grew, seeds started to resurface—corn that had been carried on the Cherokee Trail of Tears and 800-year-old tobacco.

Wilson discovered that seeds have stories to tell, both in their genetic material and in the histories of the people who grew and protected them. “Families would come forward with handfuls of seeds that were wrapped up in a handkerchief,” she said.

Wilson began volunteering for and was eventually hired as executive director at Dream of Wild Health, a Minnesota-based organization that works to reestablish traditional Native American relationships between people and plants. In 2019, she became the executive director of the Native American Food Sovereignty Alliance (NAFSA), an organization with a similar national mission.

When the Dakota were removed from Minnesota, they were also removed from the plants they relied on for food and medicine. Indigenous groups around the country experienced similar trauma as they were forced onto reservations, where the shift to a commodity food diet undermined their physical and spiritual health. Wilson says that the return to growing Indigenous foods is a form of cultural recovery and a way to rebuild the health of these communities.

As she was first learning to grow heritage seeds, Wilson, like others, had to grapple with the fact that so much traditional knowledge had been lost. “It was a huge challenge to trust ourselves enough to take responsibility again for the seeds,” Wilson said.

Wilson chronicles this process in The Seed Keeper, whose main character, Rosalie Iron Wing—a descendant of Marie Blackbird—inherits seeds from the same genetic line as the seeds that Marie and her mother managed to save. Placed in foster care at an early age, Rosalie is painfully disconnected from her heritage. The seeds are a powerful vehicle for reviving her cultural identity, but she also struggles under the weight of the responsibility and with her own lack of knowledge. When a hailstorm destroys her first attempt to grow the seeds, she is racked with grief.

“You have to enter into it from a place of understanding that this is a partnership with a living being. Then what you need to learn, it comes forward,” Wilson says. Seeds are relatives: When we plant them, we are entering into a reciprocal relationship.

In the 20 years that Wilson has been doing seed work, she’s watched the movement to revive native seeds accelerate. In the past three years, NAFSA has gone from three full-time staff members to nine. It also has a national leadership council that represents Indigenous groups around the country. One of its programs, the Indigenous Seed Keepers Network, helps Native communities grow and share their seeds, and its Food and Culinary Mentorship program teaches people how to prepare the food they’ve grown. “Food sovereignty means you need to know how to plant and grow and harvest, but also how to cook,” Wilson said. “If you're missing any part of that, then you don't really have the full system in place.”

Before the pandemic, NAFSA held events like food summits and in-person workshops. Since then, organizers have offered online events like food challenges with participants posting photos of their creations. The demand for seeds has soared. Last spring, the Indigenous Seed Keepers Network organized a seed drive, sending out hundreds of seed bundles to Native families across the country.

Wilson believes that seed keeping will only become more essential in the face of climate change. One reason that traditional seeds have to be grown out is so they have the chance to adapt to changing conditions. “Seeds aren’t meant to be stored away in a vault,” Wilson said. “The best way to make sure that they remain vital is to get them growing in as many gardens as possible.”

Doing so girds us against climate change and also builds community. “If I'm growing in my garden and you're growing in yours, and others are growing somewhere else, then the odds are one of our crops is going to survive. Then we share it out,” Wilson said. “So not only are the seeds adapting to climate change, but through the act of sharing, they are also bringing us together in community. And that's how we get back to a saner way of living in this world.”

More Online Read Sierra's review of The Seed Keeper at sc.org/seed-keeper.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club