N 64° 35.378', W 16° 44.691'

A honeymoon on a glacier, and a message to the future

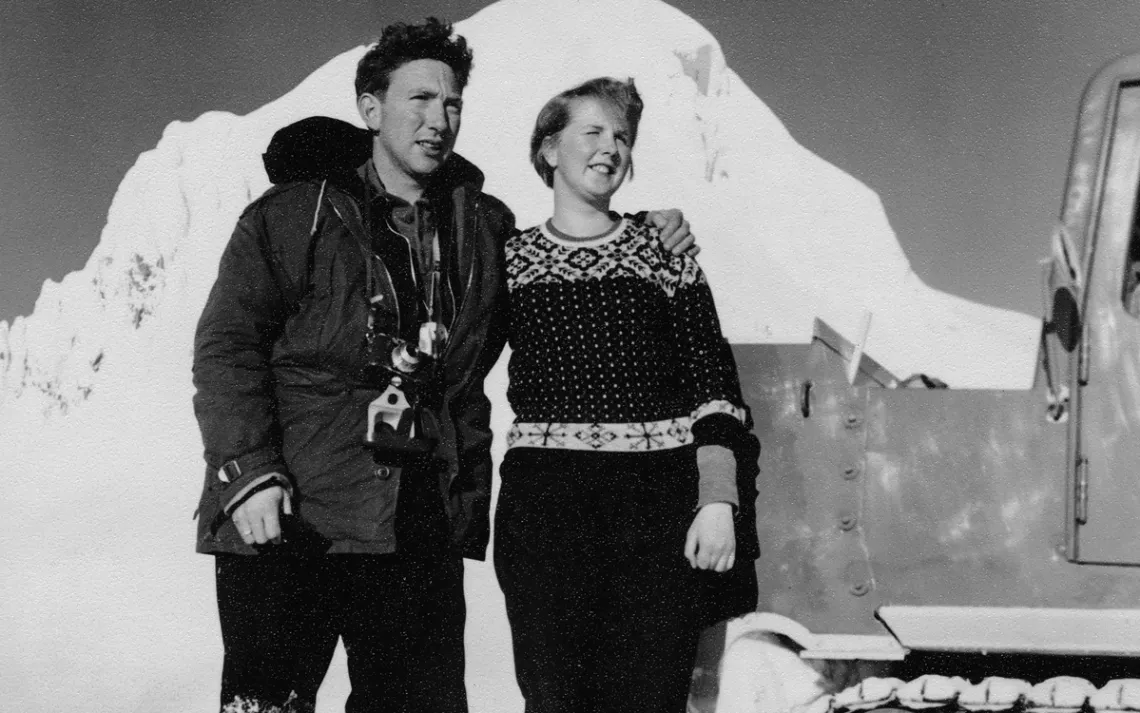

Magnason's grandparents | Photograph courtesy of Andri Snær Magnason

The essay “N 64° 35.378', W 16° 44.691'” appears in the book On Time and Water, written by Andri Snær Magnason, translated by Lytton Smith, and published by Open Letter Books (March 2021).

Grandma Hulda and Grandpa Árni’s wedding photo stands on a small table in the living room of the house at Hladbær. They’re gazing toward the horizon, standing right in front of Hvannadalshnúkur, Iceland’s highest peak, 2,119 meters high. It was the Icelandic Glaciological Society’s fifth trip since its establishment five years before.

They married on Friday, May 25, 1956, and the very next day met a nine-automobile caravan, including three snowmobiles and an energetic group of traveling companions. Gudmundur Jónasson, a mountain driver, and Dr. Sigurdur Thórarinsson, a geologist, had made a survey flight over Vatnajökull to assess whether the route was feasible; still, shifting glaciers and volcanic activity could easily derail the expedition. It was a large undertaking, and they had enough food to be out on the glacier for three weeks.

Vatnajökull was as good as unknown, a nameless land back then, like the bulk of the highlands. Only a few people had even gone onto the glacier at the time. A few research missions had been undertaken, but no regular survey or research had been carried out into the accumulation, thickness, and nature of the glacier, at least until the Icelandic Glaciological Society began its regular spring expeditions.

My grandparents stayed in a two-person tent and endured a raging three-day storm that engulfed the tent, meaning they had to stay in and wait it out. Only the very top of the tent glinted above the snow as they were eventually shoveled out. I once asked if they hadn’t gotten cold in there. “Cold?” they replied, offended, and laughed. “We were newlyweds!”

I was 11 years old when I asked, and for a long time I wondered about their answer. How did getting married make a person warmer?

The highest point of the Kverkfjöll Ridge did not have a name at the time. Dr. Sigurdur Thórarinsson wrote about this anonymous landmark in his article about the trip for Jökull, the Journal of the Icelandic Glaciological Society:

We made for the nameless bunga, a bulge or rounded elevation, which rises from the northeastern part of Kverkfjallahryggur, separated from Kverkfjöll by Gusaskard. Twice on this trip I measured with the barometer the height difference between this bulge and the more easterly Kverkfjall one; according to these measurements the bulge is about 1,760 m high, while Gusaskard is 60 m lower. We collectively named this bulge Brúdarbunga; we expect that name will stick unless another one is found soon.

Brúdarbunga, which means the Bride’s Bulge, is 1,781 meters high according to maps: Iceland’s fifteenth-highest peak. Its exact coordinates, latitude and longitude, are N 64 35.378, W 16 44.691.

The mountain cabin the group had built the year before was small and cozy, black with a red roof and with sleeping space for twenty. The group was glad to see it had survived the inhospitable winter. The cabin stands to this day, surrounded by black sand, lava mounds, and glacial deposits, near the perimeter of Vatnajökull on the west side. In the guestbook of the cabin at Jökulheimar, you can read this entry:

May 27, 1956A honeymoon trip, surveying trip, snowhole-digging trip, an airfield construction trip. Twenty-five participants, one fifth women. Arrived here a bit before noon on the aforementioned day, the Festival of the Trinity. We left Reykjavík at 16:25 May 26 with 2 heavy vehicles, “Gusi,” driven by Gudmundur Jónasson, and 6 additional automobiles. It was raining heavily all the way east to the Tungna river crossing, we arrived there at 5:30 on the night before the 27th. After two hours we’d brought everything across the river and then we drove up to Jökulheimar in clear weather. The journey was more or less clear, yet we were barely able to make it: the route was practically still closed off by snow when we came in under Ljósufjall, and if we’d been any earlier in the season it still would have been; now, there was little delay.

The expedition’s first task was to make a bed for the newlyweds with a soft mattress in the area of the hut which, according to those who examined the lodge very scientifically, had the sturdiest floorboards.

Having eaten hot soup, the whole crew lay down to sleep and most of them didn’t wake until the smell of food entered their senses again six hours later. The five women and Bjössi had prepared a delicious supper. Later that evening, a great jamboree started up in honor of the frequently-toasted newlyweds. Cups were drained and sentimental songs sweetly sung. A suitable redness flushed into the bride’s cheeks when Úlfar Jakobsson lustily sang a love song. The bride and groom were celebrated with many speeches, and the festivities were a great success. It was heartily wished at the festivities’ conclusion, and with voluble assenting, that this should not be the last honeymoon in Jökulheimar. From now on, there will always be a firm bed awaiting newlyweds! You might say this shelter is fit for the purpose . . .

Signed

Jón Eythórsson

I read the diary entry to my grandparents, and they grinned like teenagers as I read the part about the mattress on the sturdiest floorboards. My nine- and eleven-year-old daughters were sitting with us and didn’t get the joke.

According to the guestbook, the expedition’s mission on the glacier that spring of 1956 was as follows:

Survey markers to be placed on Thórdarhyrna, east Kverkfjöll, Grendil, Hvannadalshnúkur and Svíahnjúkur both east and west.

Snowfall or winter accumulation shall be measured in as many places as possible.

If conditions allow, a sledge should be obtained at Esjufjall and the Icelandic Glaciological Society lodge there checked.

Travelers, five women and one man, shall be given the opportunity to traverse as far across the glacier as conditions allow; they are not required to visit all places survey markers will be placed.

Gudmundur Jónasson was the tour leader, nicknamed “Mayor of Grímsvatnahreppur.” He drove his snow truck, nicknamed Gusher, and handled radio and telephone connections with the outside world. The geologist Sigurdur Thórarinsson took care of snow measurements; the cook (and bursar) was Árni Kjartansson and another cook was Mrs. Hulda Gudrún Filippusdóttir. Ólafur Nielsen drove Grendel, a snow truck, and Haukur Haflidason drove Jökull 1. There was Ingibjörg Árnadóttir, Grandma Hulda’s best friend, and Nick Clinch, a celebrated mountaineer from America who worked as a lawyer with the defense force at Keflavík Airport Base. He went on to be the first person to climb the impassable Hraundrangur and later climbed many of the world’s toughest peaks and wrote books about his adventures.

This lively group literally went all across the glacier from Jökulheimar to Kverkfjöll. At selected places, pits were dug to survey winter snow accumulations and markers were set up on the peaks for surveying. At the summit of Hvannadalshnúkur, a two-meter-high barrel was installed and thus the travelers could stand two meters above the highest peak in the country. Sometimes they had to travel blind, relying on compasses and altimeters. Considering the era’s technology, incredible distances were crossed; at the time, the most dangerous crevasse regions had not been mapped properly, or even found at all. The glacier is more than a thousand meters deep at its thickest. A whole kilometer of ice. The transceiver reception malfunctioned so they could only communicate outward to the wider world without knowing if anyone could hear. The journey was heavy going and soon they were low on gas out on the middle of the vast glacier and had to act fast to save themselves:

On June 10, four of us made an attempt to get to Grímsvötn to get gas. We weren’t able to take the Weasel more than 5 km, due to a lack of fuel, after which we continued on skis. The ride was hellish and the weather worse. We thought ourselves fortunate when we got back to the camp site, having trekked about 35 km, having struggled and remaining unsupplied. We would hardly have found the campsite if we had not been so ingenious as to pile snow cairns at short intervals all along the way.

I show Grandma Hulda and Grandpa Árni a video, a movie Grandpa Árni took on 16 mm film during the honeymoon. One shot was taken down the mountain and another of the group on skis being pulled behind the snow vehicle. It’s an enchanting time, adventurous. I ask if they weren’t ever worried about crevasses or cracks opening up in the middle of the glacier.

“We had a kitchen tent and made a hole for food scraps and waste. We didn’t understand why the hole never filled up. We’d only gone and camped on top of a four-hundred-meter-deep crevasse!” Grandma Hulda laughs. “We were lucky that we didn’t lose anyone on these trips. There were no major accidents.”

“And you never got lost?”

Grandpa Árni thinks about it. “No, I never got lost. When I was in the mountains, the conditions could get bad enough that I didn’t know where I was, but there was nothing to do other than dig into a snowdrift and wait out the weather, sometimes for a few days. If no one was expecting me back home, no one would start looking, so I wasn’t exactly lost. As soon as it was clear again, I could continue the journey.”

“The best thing was hanging off the back of the snow truck and letting it pull us along,” Grandma Hulda says. “We could ski down the slopes that way. Once, we hung from the back of the vehicle all the way from Kverkfjöll to Jökulheimar, ninety kilometers. Everyone gave up except for Árni and me.”

“But don’t you want to go back to the glacier?”

“Yes,” says Grandma Hulda. “I would like to go, but Árni isn’t fit for glaciers these days.”

“It’s just far too easy today with those monster trucks.” Grandpa Árni grins. “It’s no fun when things are so easy.”

“What’s odd,” says Grandma Hulda, “is that in the spring I can sense the smell of the glacier and I find myself longing to go back.”

“The glacier’s smell?” I ask.

“Yes, there’s a particular scent to the air in spring, a glacier scent.”

“What does it smell of?”

“Well, just glacier! You can only describe the scent by experiencing it. When you’re up on Vatnajökull everything disappears; you forget everything. An infinite vastness. An absolute dream.”

Sigurdur Thórarinsson’s article about the trip in Jökull also discussed the research the team conducted:

Most of the measurements carried out by Vatnajökull expeditions in recent years remain unfinished. When these measurements have been completed—glacial thickness measurements, triangulation measurements, and snow accumulation measurements, as well as observations on changes in the Grímsvatn area—we hope that our knowledge of this largest glacier in the country will have been reasonably satisfied. In all likelihood, this glacier will never be fully researched.

When the first trips of the Icelandic Glaciological Society were conducted, people knew that Iceland’s glaciers were living. A glacier is defined as an ice mass that moves under its own weight. Glaciers are semifluid, and the largest are like a kind of conveyor belt: Winter snow gathers on the accumulation areas and becomes ice that flows slowly down into the valleys via outlet glaciers, where it melts. A healthy glacier is in equilibrium. It collects as much snow as it delivers via loss of water. Its income equals its expenditure. In Iceland, a glacier’s uniqueness lies in the interplay of fire and ice, with eruptions under the glacier giving rise to jökulhlaups: massive, dangerous glacial outburst floods that can achieve the volume of the Amazon in a short period.

A plane landing on a glacier serves nicely as a benchmark for understanding glaciology. The plane Grandpa Árni and his companions dug out was covered in several meters of snow one year after landing on the glacier. Over time, it would have burrowed farther down, then moved slowly along with the flow of the glacier toward the next outlet glacier. There it would have resurfaced as part of an ice tongue, possibly after a thousand years. The ice that calves into the glacial lagoon Jökulsárlón is snow that fell on Vatnajökull’s summit at the time of Iceland’s settlement over a thousand years ago.

In 2019, Vatnajökull is about 8,000 square kilometers, roughly 10 percent of the size of Iceland; its total volume is around 3,200 cubic kilometers. If the glacier was evenly distributed throughout Iceland, the land would be covered by a thirty-meter-thick layer of ice. Helgi Björnsson, a glaciologist, told me that the glacier contains water that is equivalent to twenty years’ worth of rainfall across all of Iceland; if it melts, the world’s oceans will rise by a centimeter. Forecasts of up to a hundred centimeters’ rise in sea level mean that the equivalent of a hundred Vatnajökulls will disappear across the world in the next one hundred years. Vatnajökull has already added one millimeter to the surface of the ocean because it reduced by 10 percent during the twentieth century.

Vatnajökull reached its high point, having grown steadily for more than five hundred years, during what’s known as the Little Ice Age, a phenomenon regional to the Northern Hemisphere that occurred from the sixteenth to nineteenth centuries. All that accumulation seems to be going in the other direction now, and within just a hundred years, as a result of the worldwide conditions of global warming. Since the turn of the century, the glacier has been reduced by 4 percent, thinning by over half a meter a year. That’s almost a hundred cubic kilometers of ice.

Other glaciers in the country, Langjökull and Hofsjökull, are retreating even faster. Estimations have Snæfellsjökull disappearing by 2050. Okjökull is already gone. Okjökull was the first known Icelandic glacier to formally lose its status as a glacier. This formerly fifty-square-kilometer ice cap is now one square kilometer of dead ice. Vatnajökull’s equilibrium line is at 1,200 meters; at that height, the glacier maintains itself. If a large part of the glacier falls below this mark, snow will cease to accumulate and if that happens, melting will significantly accelerate. That change would be irreversible unless a much colder climate were to emerge. Were a plane to land on the glacier and be buried under winter snow, it would reemerge the very next summer when the snow melts, instead of digging itself farther and farther down. When the glaciers are gone, what is Iceland? Land?

The Icelandic Glaciological Society is a remarkable organization because it’s not only for glaciologists, scientists, and others working in glacier-related fields; it also includes a community of amateur scientists and volunteers from the general public. For a poor nation, multiperson three-week expeditions of this kind would have been impossible without a mix of people involved: geologists, mountaineering enthusiasts, adventurous truck drivers, adept builders who could construct shelters on the glacier. It was the enthusiasts from among the general population who enabled the scientists to achieve their goals, and the scientists in turn gave those enthusiasts more depth and purpose. More often than not, work was completed by volunteers (although some of it was funded by the National Land Survey and the Icelandic Hydrological Survey). This was in part the same group of people who founded the Air Ground Rescue Team: mountain and outdoor enthusiasts who dash from work and family commitments to respond to accidents and natural disasters or to search for missing persons. Icelanders have never had the resources to fund a whole rescue team; the strength lies in it being carried out by volunteers.

The Icelandic Glaciological Society’s spring trips began in 1953, and Grandma Hulda and Grandpa Árni continued to make these trips well into the 1970s. The expeditions’ surveys cover more than sixty years, and they can be combined with weather data and scientists’ forecasts of where the earth is headed.

In 1958, Charles Keeling began regularly measuring carbon dioxide (CO2) in the atmosphere at the Mauna Loa volcano in Hawai'i. Measurements there have shown how the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere has been increasing rapidly. At the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, the ratio was about 280 parts per million (ppm). By 1958, industrialization had caused a significant increase, to 315 ppm, higher than the highest levels measured on earth for hundreds of thousands of years. Now we have reached 415 ppm, adding about 2–3 ppm a year. The warming of recent years and Vatnajökull’s response to it give clear indications of what will happen to the glacier in the coming decades.

Given the rising temperature of the earth, Vatnajökull’s main outlet glaciers will disappear in the next fifty years; the glacier itself will almost entirely disappear within a hundred fifty years. This will happen far sooner if Earth’s average temperature rises by more than two degrees Celsius. As my grandparents embarked on their glacier expeditions, glaciers were a symbol of something great and eternal, like oceans, mountains, and clouds. In 1955, many of the country’s outlet glaciers had somewhat retreated from their turn-of-the-century position, but Vatnajökull was still something that seemed eternal. An eternal white giant. Its scale of change was many centuries, even a millennium. Vatnajökull is now diminishing on a human scale: 10 percent shrinkage over a hundred years is high speed; 100 percent shrinkage in a hundred fifty years is a disaster. Today, gigantic glacial outlet tongues retreat tens or hundreds of meters annually. For geological phenomena like Vatnajökull to disappear in just over one human lifetime is beyond our comprehension. The size gets lost in the vast buzz.

Spring 2019 marked the first time no one was able to travel up to Vatnajökull from the shelter at Jökulheimar:

The Icelandic Glaciological Society’s spring expedition has taken place annually since 1953. Most often the trip heads out onto Vatnajökull from the west, through Jökulheimar and Tungnaárjökull [. . .] But Tungnaárjökull has retreated so far that the area in front of it has become impassable to vehicles due to the wetness of the ground. No viable route has been found this spring. This is the first time in 66 years of spring expeditions this has happened. These changes are a direct result of global warming. Tungnaárjökull, like other glaciers, is retreating rapidly and what emerges from under it is land that has been covered over by glaciers for at least 500 years.

Watching the movies Grandpa Árni recorded out on the glacier, I once told him he should have shot more images of Grandma. She was only young once, I reckoned, but it would always be possible to film the glacier and the landscape. I was wrong. The glacier turned out to be as ephemeral as a person. The films Grandpa Árni took document a landscape that won’t last much longer. If my youngest daughter lives to be as old as her great-grandma, she will still be alive in 2103. It is pure science fiction to think so far ahead. By then, Skeidarárjökull will be long gone, Langjökull mostly gone, Hofsjökull, too.

Where the glacier once touched the sky, there will be only sky. Our grandchildren will look at old maps and try to imagine a mountain made of frozen water. They will try to understand its nature. A thousand meters of ice filling a whole valley? They will draw lines in their minds and strings between peaks, imagining a glacier that is so thick the world’s tallest towers pale in comparison. They will point to the air and say, “That’s where the campsite was. Up there, right under the clouds, that’s where the two of them pitched up on their honeymoon.” Our grandchildren will try to conjure mental pictures, try to envision a snowmobile traveling across the sky towing singing skiers. It is impossible to imagine what else will be happening in the world at that time. And impossible to say what words and concepts will be used about our time. It depends on us, on what we do right now.

In the summer of 2019, I was given the strange task of writing a memorial for the Okjökull glacier, the first of hundreds of glaciers Iceland will lose over the next two hundred years. It took me quite some time. I wondered who I was addressing with the words on the plaque; I wondered at the absurdity of the task. How do you say goodbye to a glacier? In the end I came up with this:

Ok is the first Icelandic glacier to lose its status as a glacier. In the next 200 years, all our glaciers are expected to follow the same path. This monument acknowledges that we know what is happening and what needs to be done. Only you know if we did it.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club