Fanatical Rock Fans

With so many amazing rock formations in canyon country, why is everyone stuck on the Wave?

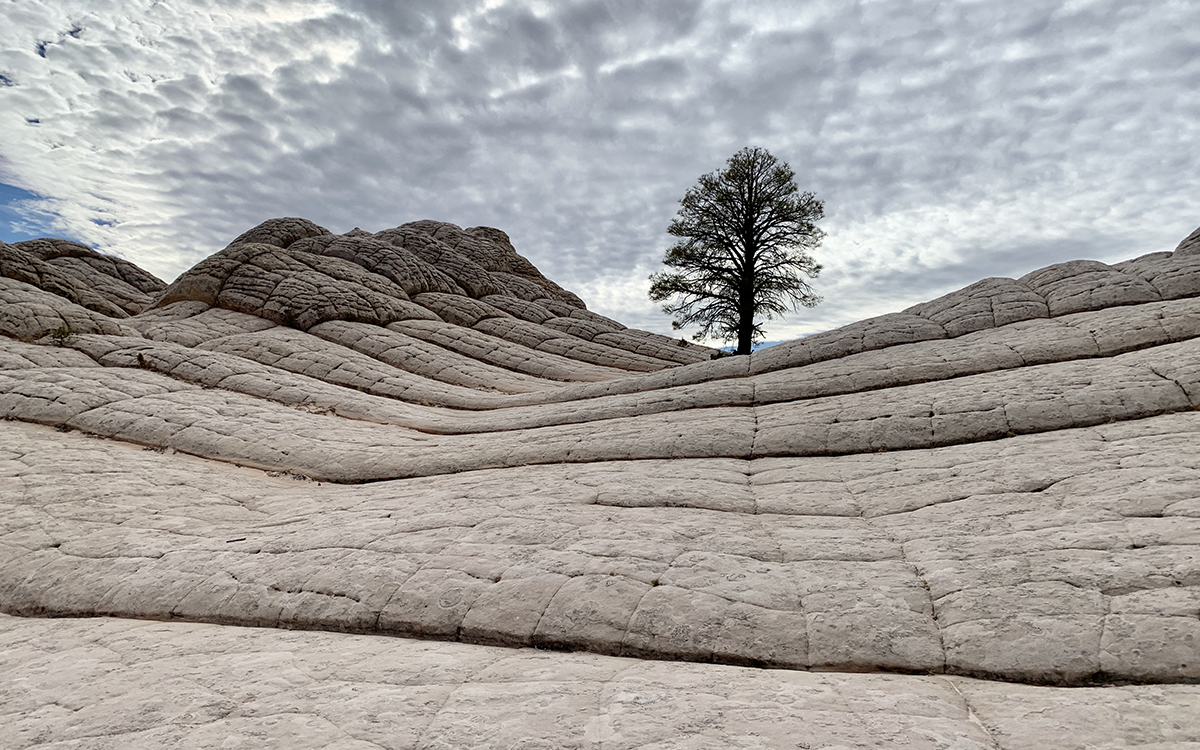

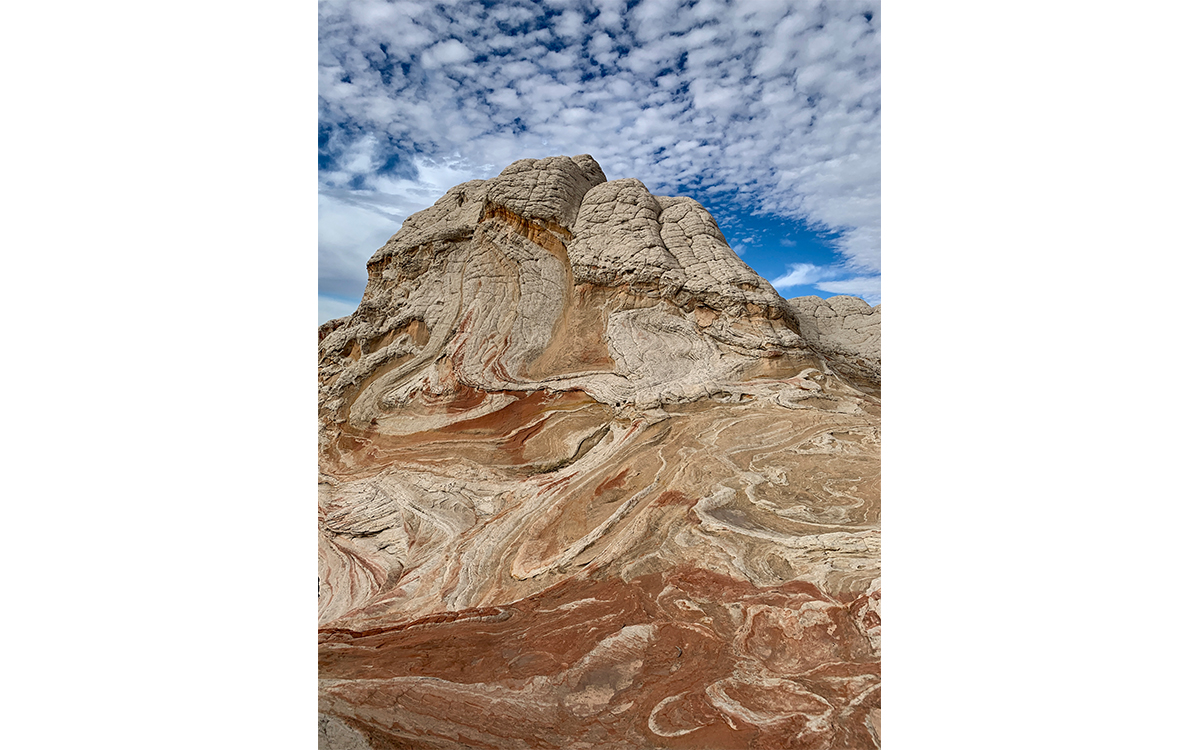

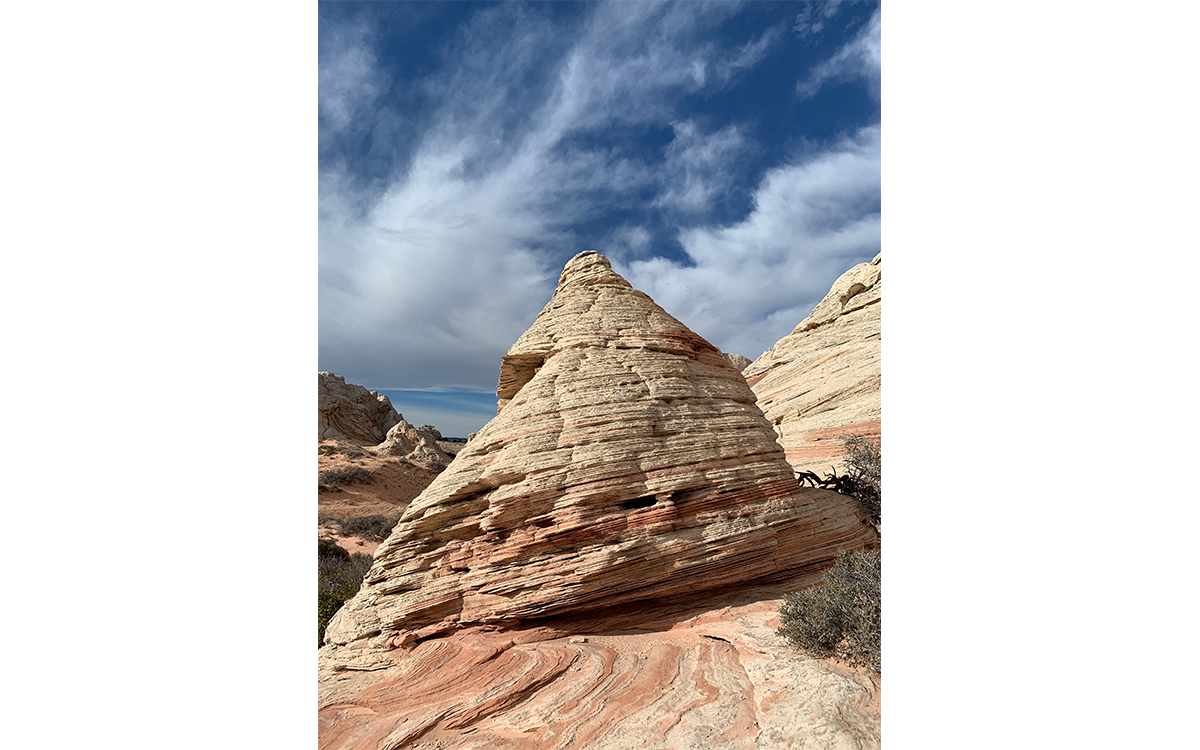

Photo by Melanie Haiken

“There are lots of beautiful rock formations out here,” says Scott Owens, a guide with Antelope Canyon Tours. He gestures toward the peach, pumpkin, and scarlet-hued bluffs of the aptly named Vermilion Cliffs as we jounce by them in a cloud of dust. “There are slot canyons, bluffs, plateaus, and plenty of other areas where the colors are really bright. But everyone wants to show pictures of the Wave.”

We’re on our way to White Pocket, perhaps tops among the vividly photogenic locations Owen is referring to but still relatively unknown due to its remote location. Less than 10 miles away as the crow flies is the Wave, the hallucinogenic swirl of striped sandstone instantly recognizable from countless Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter feeds. Located within a vast stretch of desert on the Utah-Arizona state line protected as the Paria Canyon–Vermilion Cliffs Wilderness Area, the Wave was one of the very first social media stars, the vanguard of a phenomenon that’s since led to damaging overtourism—and the necessary protective responses–that we now see across the country.

According to local lore, until about 10 years ago only hardy hikers, local tribes, and wilderness guides knew about the isolated slice of sandstone within the remote Coyote Buttes. Then photographs began to turn up on social media and make their way into popular computer wallpaper slideshows. In 2007, the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) received 5,800 online permit requests to visit Coyote Buttes North, where the Wave is located; by 2013 that number had swollen to 68,666, with another 18,200 people applying in person. In 2018, the total number of permit applications reached a record 168,317.

Out of those, just 7,300 people–about 5 percent of all applicants—will make the six-mile round-trip trek this year, thanks to BLM’s strict limit of 20 entrance permits a day: 10 via an online lottery that opens four months in advance and 10 issued on a walk-in basis, also by lottery. Another 20 people a day receive permits for Coyote Buttes South, a similar but slightly less colorful sandstone formation.

Fully grasping the insanity that is the Wave requires attending the lottery, held every day at 9 A.M. at the Grand Staircase–Escalante National Monument Visitor Center in Kanab, Utah. Packing the walls and sometimes spilling out into the hallway, the applicants—who come from all over the world—share their stories of entering their names again and again, in some cases every day of an entire two-week international trip.

The odds for the online lottery are even worse. In October 2019, the month taking applications at press time, between 182 and 336 people had already requested permits for every available date, with more than two weeks of sign-ups to go.

There’s a good reason, of course, for the protections. Navajo sandstone, even when calcified as it is here, is soft and can be worn down by thundering feet. But more than that, this is the desert, and it’s no joke to find your way around. Paths disappear as they cross rock, temperatures can rise well over three digits, shade is nonexistent, and the rock itself stores and reflects heat back onto those crossing it.

Last July, a 49-year-old father from Belgium died from exposure after becoming disoriented, leaving his 16-year-old son to hike out for help, and in 2013 three people died in two separate incidents. Injuries are common as well.

“Weather and road conditions can make reaching the trailhead difficult due to flash floods, and visitors may encounter challenges with way-finding to reach the Wave as the trail is undeveloped and unmarked,” says Rachel T. Carnahan, a public affairs officer for the BLM’s Arizona Strip District. Successful permit-holders receive a map and route description, which includes a photo guide and GPS coordinates.

A hiker takes a photo on a rock formation known as the Wave in May 2013. | Photo by AP Photo/Brian Witte

The Next Wave?

Getting to White Pocket is even harder than getting to the Wave. It requires an almost-two-hour drive over unmarked dirt roads that wash out in flash floods and disappear under drifts of sand. “Locations such as Coyote Buttes South and White Pocket are even more remote [than the Wave] and cannot be reached without the use of a high-clearance four-wheel drive and advanced backcountry-driving skills,” says Carnahan, adding “Many of the sites throughout Vermilion Cliffs National Monument don’t have mobile coverage, and it may take hours for volunteer search and rescue teams to reach and assist visitors.”

On our way, as we pass unmarked tracks turning off toward various trailheads, Owens ticks off more favorite rainbow-rock photo ops: Buckskin Canyon, Wire Pass, Thousand Pockets, Horseshoe Bend, Antelope Canyon, and, of course White Pocket.

What do they have in common? It all comes down to geology, says Carnahan. “The large-scale, high-angle geologic cross bedding that occurs at the Wave and White Pocket were 190 million years in the making, starting with the early Jurassic age,” she explains. “The variety of colors—including red, pink, yellow, and brown—are due to the oxidation of iron-bearing minerals within the Navajo and Kayenta sandstone.” The reds and pinks come from the mineral hematite while limonite and goethite lend the rocks their ochres, golds, and browns.

Once we reach White Pocket, though, scientific explanations cease to matter; in fact, words aren’t much use at all. There’s a reason why it’s taken photographs of these formations to alert the world to their true wonder. First comes a moonscape of pillowy white drifts, rising to the sky with an eerie glow. Then come the layers, like swirls of butterscotch, caramel, and vanilla cake batter at the first stir of the spoon.

In the pockets between the colored strata are strewn strange gray balls, perfectly round and oddly heavy. They’re moqui marbles, Owens tells me, heavy because the sandstone is coated with iron. We see a few hikers in groups of twos and threes but largely have the place to ourselves. It’s clear, though, that won’t be the case for long.

“We have a lot more people asking about White Pocket this year than we did last year,” says Arden Redshirt, co-owner and manager of Antelope Canyon Tours. And that’s just on the Arizona side, he says—there are many more tours coming in from Utah. “Every time new photographs appear, we get more calls.”

In my role as a writer, of course, I’m in the thorny center of this issue. Even as my camera snapped continually, I worried about whether or not to share the images it was capturing. “The social media dilemma is real,” says Taylor McKinnon, senior public lands campaigner for the Center for Biological Diversity. “On one hand, it’s helped the public realize its spectacular public-lands heritage just as it was starting to be forgotten. But it’s also popularizing places to the point of long-term damage.”

Photos by Melanie Haiken

The Ongoing Question of Permits

Meanwhile, the access debate took a new twist in May 2019, when the BLM announced it was considering loosening restrictions on the Wave, expanding the number of permits from 20 to as many as 96, the highest number allowable under the current usage plan. The reasoning, says Brandon Boshell, Vermilion Cliffs National Monument manager, is demand and the need to balance that with wilderness protection and safety.

“It’s not just the 168,000 applications—all of our offices, from mine to the state office all the way up to the bureau, are receiving a steady stream of phone calls, emails, and special requests for access. That coupled with some secretarial orders asking the bureau to increase access made us take a hard look.” Three meetings were held in early June in Page, Arizona, and Kanab and St. George, Utah, with a public comment period that at press time had just been extended into the fall. Environmentalists are already gearing up to fight the change, with a decision not expected until early 2020.

“Current use levels have already caused harm,” says MacKinnon. “Quadrupling use would quadruple impacts, damaging the very things people are coming to see and experience. Loving the place to death, which this plan threatens to do, would be a terribly shortsighted thing to do.”

Other areas, too, are dealing with the travails of social-media-driven demand. Scott Owens cites Horseshoe Bend, a dramatic curve of the Colorado River, as an example. A new viewing deck was completed in the summer of 2018, payment for parking was instituted in April, and a 300-car parking lot is under construction. “Five years ago, there was hardly anyone there. Now there are cars lined up all the way up Highway 89 and there’s a drop-off point for tour buses. Tour buses!” He shakes his head. “You used to be able to just pull up and look down and now you can’t get near it.”

Will the BLM eventually start restricting access to White Pocket? No plans are in the works, but Redshirt thinks it’s a possibility if things keep going as they are. “Right now there are no limits on how many people can go in there, but I think it might come to that point because with all the attention, we’re going to see more and more people heading that way, and we don’t want to overrun it.”

McKinnon thinks restrictions are a good idea. “The same principles applying to the Wave apply to White Pocket—the BLM needs to get a handle on the amounts, types, and locations of appropriate use,” he says. “Navigating that dilemma puts a lot on the shoulders of public lands managers. But this isn’t new, and the Colorado Plateau is full of examples of resource-protective use quotas, be that Cedar Mesa, Navajo National Monument, or any of the major rivers, most notably the Colorado River through Grand Canyon.”

For the moment, bad roads and lack of cell service may be the best protection White Pocket and other areas of the Vermilion Cliffs can hope for. Going with a guide who can help ensure the area’s protection is the best choice for those who want to visit sustainably.

On the long drive back, we pass a giant pit in the sand. Deep tire tracks lined with pieces of wood show where a vehicle had been spinning out. A few minutes later, a couple in an ATV pulls out of a side track to ask for directions. Owens consults, pulling out a map to show them where we are. “It’s a good thing we stopped to ask you. We were going completely the wrong way,” the woman says, the guy looking chagrined.

“You see them every time,” Redshirt says, as they fade out of sight. “We keep telling people to come with a guide, but they all think we’re exaggerating, or just trying to get business. We just want to protect it all—the area itself and the people visiting it.”

Photo by Melanie Haiken

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club