Fatal Washington Mountain Lion Attack: The Postmortem

Sometimes doing everything right isn’t enough

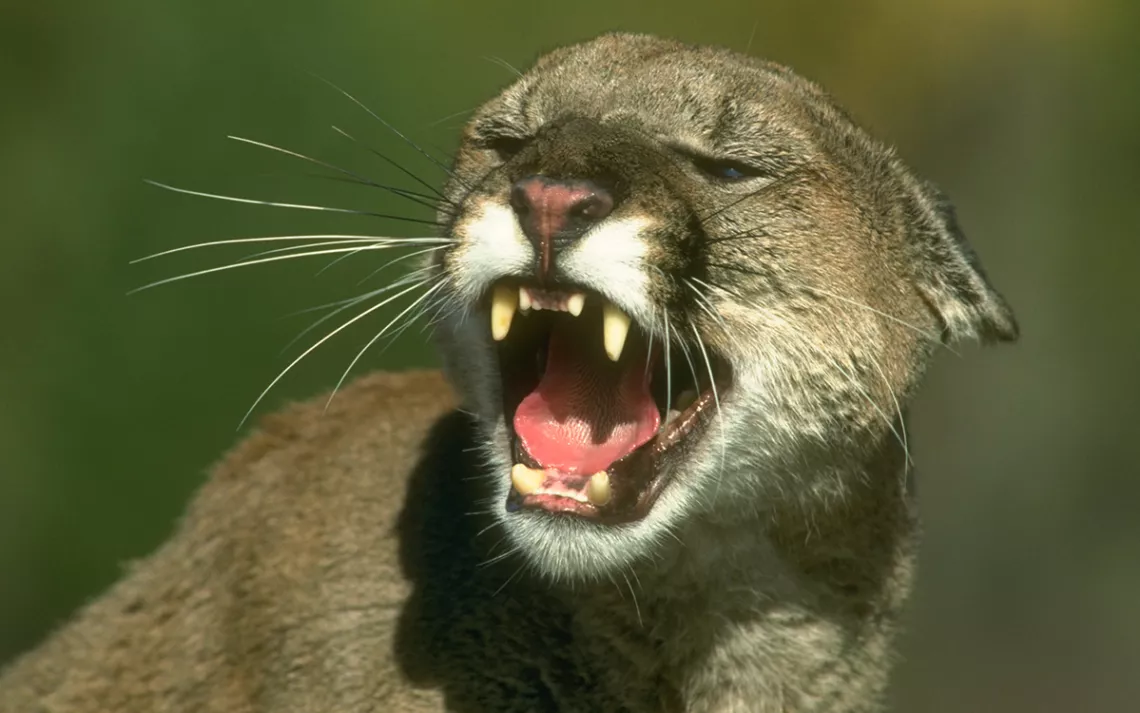

Photo courtesy of Wildlife California Department of Fish and Game

On Saturday, May 19, a three-year-old male cougar attacked two Seattleites while they were mountain biking along logging roads near Lake Hancock, in the foothills of the Cascades 30 miles east of the city. It was the state’s first confirmed fatal cougar attack in 94 years. Isaac Sederbaum, 31, a social science researcher, was treated for his injuries at a nearby hospital and has been released; SJ Brooks, 32, a leader in the local cycling community, especially around advocacy and inclusion initiatives, was killed.

While the pair initially scared off the lion using what Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW) police say was correct behavior—yelling, standing their ground, and even hitting it with their bikes—it returned and attacked again, biting Sederbaum. Brooks fled, and the cougar released Sederbaum, who went for help, whereupon it returned to Brooks and killed them (Brooks preferred they/them pronouns).

WDFW Captain Alan Myers, whose team responded to the attack, told Sierra that this is the first time in his career that he’s heard of a cougar attacking someone after being scared away.

Veterinarians at Washington State University, Pullman, are performing a necropsy on the cougar, which WDFW police hunted down with the help of a contractor. They are trying to determine whether it was ill. Contrary to media reports that the animal was emaciated, Richard Beausoleil, WDFW’s bear and cougar specialist for the past 16 years, said that while it was thin, it did have fat reserves. “It wasn’t on death’s doorstep,” he said.

Agents with the Washington State Fish and Wildlife police tracked and killed this cougar that is believed to be responsible for attacking two mountain bikers in the woods northeast of Snoqualmie on May 19. One person was fatally injured and the other was released from Harborview Medical Center Tuesday. | Submitted image

While many mourn Brooks (and have already established a scholarship fund in their name), the cougar’s unprecedented behavior—and lack of clear explanation for it—have people across the country concerned for the safety of both humans and cougars.

Are such incidents the price of sharing space with large carnivores? If not, how do we coexist with them in a way that prevents tragedy from happening again?

“A majority of my job is just to message with folks and keep them grounded in the reality of humans and wildlife and how they interact,” Myers said. Washington is home to some 2,100 cougars; over the past century, the state has experienced two fatal cougar attacks. In the same period, all of North America has seen 95 nonfatal attacks and 25 fatalities.

Yet public perception of the risk is skewed. In 2010, Beausoleil surveyed Washington residents for the WDFW’s Cougar Outreach & Education in Washington State study. He and his team found that “57 percent overestimate cougar-related injuries in the lower 48 states. . . . It is estimated that less than one person per year is injured by a cougar in the lower 48 states.”

“The odds of getting struck by lightning are higher than the odds of getting attacked,” said Earthwatch chief scientist Cristina Eisenberg, “but it is our human nature to react with fear to something like this.” Myers agrees. “Attacks are extremely rare all across the spectrum of wildlife. When they do occur, they're very tragic situations of course, but they catch people’s imagination, which oftentimes causes folks to have a visceral, natural reaction of fear of the outdoors for a while.”

Washington brings in $26.2 billion annually from outdoor recreation, in which 72 percent of its 7.4 million residents participate. Even more people are expected to play outside over the coming decade: The state is on pace to reach more than 8 million residents by 2030, up from 4.13 million residents in 1980. According to the Washington Trails Association, each year 100,000 people hike Mt. Si, a popular trail outside of North Bend just miles from where the cougar attack occurred. North Bend itself has seen its population increase from 1,701 in 1980 to 6,578 in 2014, helped by explosive real estate costs forcing Seattleites to venture farther from the city for housing.

The increasing numbers of recreating humans concerns wildlife managers. When I asked Beausoleil about who is responsible for the majority of cougar encounters happening these days, he didn’t hesitate: “It's people,” he said. The hobby farming of goats, sheep, and chickens draws cougars to the border of suburbia, and “[lion] interactions with people tend to include bikers, joggers, and walkers in the backcountry. In almost all instances, they're surprise encounters. Animals are using the trail systems just like people—to get where you're going quick.”

Earthwatch’s Eisenberg cautions that cougars may attack what they don’t understand: “We live in a world where the human density is perhaps greater than it ever has been, with things like bicycles that propel us rapidly through landscapes, which was not the case in the past. Sometimes these carnivores react.”

In Beausoleil’s survey, two-thirds of respondents reported not knowing how to handle a cougar attack. Beausoleil and Myers advise the following:

- Get the animal’s attention. “Yell, holler, and scream to make sure the animal knows you’re there,” Myers says. Beausoleil advises wearing and using a whistle.

- Don’t run. Stand your ground.

- Make yourself look big by waving your arms.

- If the animal doesn’t leave, it’s time to bring out bear spray, which you should have already taken the time to learn to use. It works just as well on cougars as bears. “It’s over 99 percent effective [and] cheap insurance,” Beausoleil says, advising that bikers should consider bear spray bottle cages for easy access, and hikers should get belt-clip canisters. “You have to wear it on your belt. You cannot put it in a backpack. You will not have time” to use it otherwise.

- If all this fails and the cougar attacks, fight back—no matter how useless you may feel fighting a 140-pound cat. “In most instances of a cougar attacking a human, the human wins if they fight back because cougars are not used to prey that fights back,” Myers says, noting that a cougar’s diet consists mostly of deer. “Don't give up the fight. It's literally a fight for your life.”

In talking with the public, Myers reminds people that “we're part of this ecosystem and not above it.” Washington residents seem to agree: In the 2010 cougar survey, 90 percent of respondents “believe it is the responsibility of people to help prevent cougar conflicts when living in or near cougar habitat.” That means preventing encounters with predators in the first place. WDFW suggests that outdoorspeople hike in groups; avoid hiking after dark; keep children close by and in view; not approach dead animals; stay aware of their surroundings and for signs of cougars; and keep a clean camp.

Thus far, Beausoleil said, public reaction to the tragedy has been reasoned. “We're seeing a very educated and informed public that is very sad but understands that risk is a part of living here—and that cougars have every right to be there, just like we do.”

Eisenberg believes that appreciation for how cougars may perceive us can help people better empathize, and stay safer.

“People think that [cougars] are out to stalk us, and that's not how the majority of those animals think,” she said. “Messing with us is low on their agenda. They just want to eat and reproduce and have a quiet place to rest. We're doing our thing and they're doing their thing, and they just want to avoid us.

“It is dangerous to recreate outdoors where there are carnivores, or to work outdoors where there are carnivores, and you have to be aware of those hazards. One of the ways I've stayed safe around carnivores all these years is by being very respectful,” she added.

While the cyclists in Saturday’s cougar attack realized they were being stalked and adjusted their behavior accordingly, Eisenberg said, “recreationist culture is such that some people just don't really pay attention. They're out there to have a physical challenge outdoors, to have fun, or to enjoy a beautiful place. They're thinking about themselves more than they are the holism of what's going on around them.”

In 15 years as a professional wildlife ecologist, Eisenberg has only been stalked once. A critical tool for staying safe, she said, is simply keeping tabs on your intuition: “If you start to get this feeling that maybe you shouldn't be there, then you shouldn't be there. I’ve gotten those feelings, and that's actually what saved my life the one time I was stalked.”

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club