February Stargazing: The Moon and the Mob

Our closest neighbor reflects back to us the sun—and our own shortcomings

Photo by Ryan Miller

Last month, NASA was forced to shut down a rocket test at its Stannis Space Center in Mississippi. The space agency has shared few details but did announce that one of the spacecraft’s four massive engines suffered a "major component failure." The 212-foot-tall rocket, known as SLS, an acronym for Space Launch System, is the replacement for the shuttle program, which ended in 2011. Eventually these skyscraper-size spacecraft will carry people once more to the moon.

It’s a mission nearly a half century in the making. Human beings haven’t been back to the moon since 1972, when a crew of three American astronauts, part of the Apollo 17 mission, spent three days on the lunar surface. To date, a mere 12 people have set foot on the moon's dusty soil.

For millennia, the moon has dominated our view of space, even though it is, relatively speaking, a tiny object in the grand scheme of the cosmos. Its diameter is one-quarter that of the Earth. (Though it is large as far as moons go, ranking fifth in size among the known satellites in our solar system.) Because of its proximity—orbiting at a distance of roughly 250,000 miles—it has an outsize presence in the night sky, and we cannot help but stare in awe.

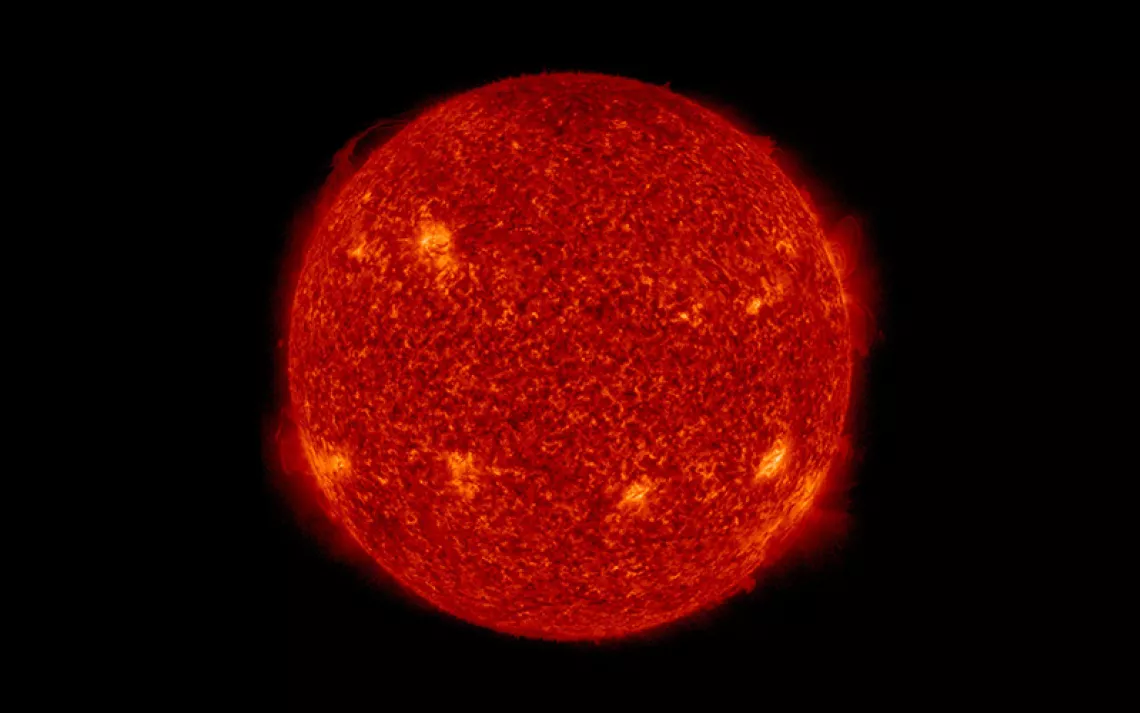

The mythology surrounding the moon is vast and probably as old as human culture itself. Many legends portray the moon as connected, and often in opposition to, what seems to the Earth-bound observer its celestial counterpart—the sun. According to the Cree people of Canada, the moon came into being after the hero Wesakechak banished the daughter of the caretaker of the sun into the sky. This, as the story goes, was punishment for arguing with her brother about who would build the campfire after the death of their father. For their bickering, Wesakechak cast them into the heavens. There the two would light the campfires of day and night. But they were also separated for eternity—like the sun and moon themselves—seeing each other only from across the vast chasm of the sky.

The ancient Greeks personified the moon as the goddess Selene, who piloted her lunar chariot across the sky. Like the moon, Selene was resplendent, her beauty celebrated by the likes of the epic poet Homer:

From her immortal head a radiance is shown from heaven and embraces earth; and great is the beauty that ariseth from her shining light. The air, unlit before, glows with the light of her golden crown…

The fetching Selene is attached to many lovers in the Greek pantheon, but most often to Endymion, a mortal who, according to some historical accounts, was not merely a mythological figure but an ancient astronomer who studied the movements and phases of the moon.

Even in antiquity, the moon’s bright visage seduced revolutionary scientific thinkers. In the fifth century B.C., the Greek philosopher and astronomer Anaxogras was exiled for suggesting that the moon was not a shining god but an object. In one of the few snippets of his work that have survived the ages, Anaxogras wrote, “It is the sun that puts brightness into the moon,” which is, of course, correct. By using empirical observation, he theorized that moon phases were based not on some ineffable quality but geometry, namely its position in relation to the sun.

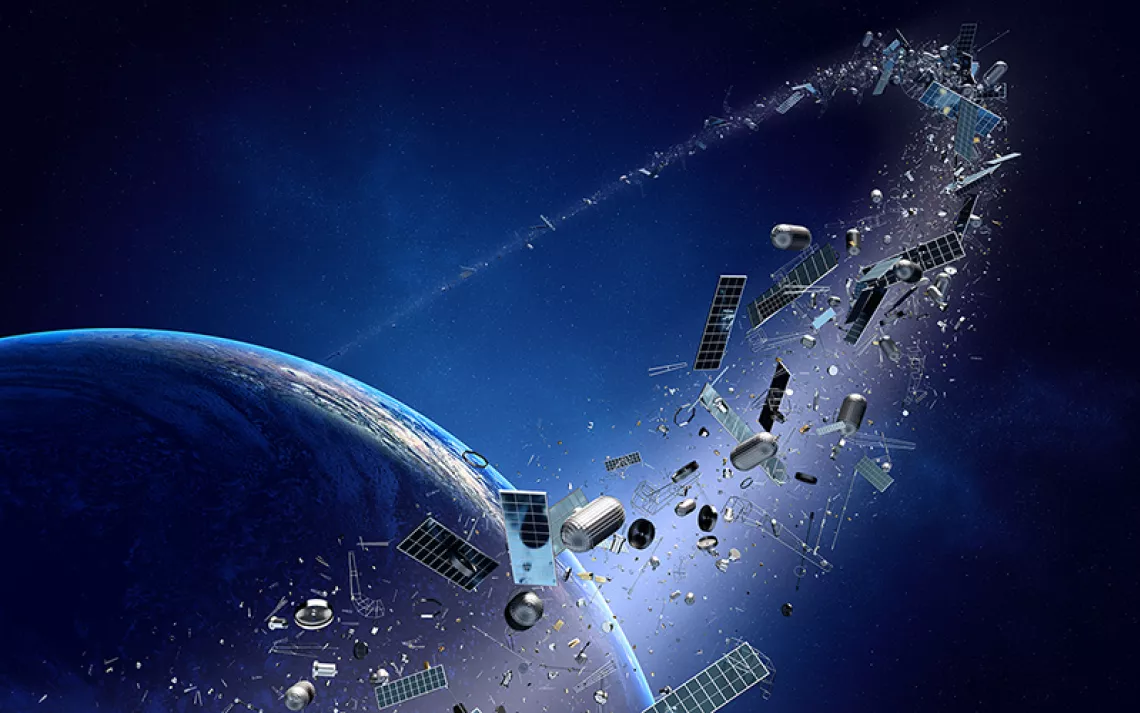

Though our scientific understanding of the universe has increased drastically in the past four decades, getting to the moon remains challenging, as last month’s failed rocket test revealed. And while technology has vastly improved from what was available during the Apollo missions, we also live in more litigious, less daring times. It’s hard for us today to imagine the risk-taking involved in safely depositing those first astronauts on the surface of another world. The Apollo missions, indeed, were a "giant leap for mankind," leading to great advancements in spaceflight as well as to a deeper understanding of Earth’s only satellite. They also confirmed what we already believed to be true—namely that the moon is a waterless, lifeless sphere.

So why do we still want to go?

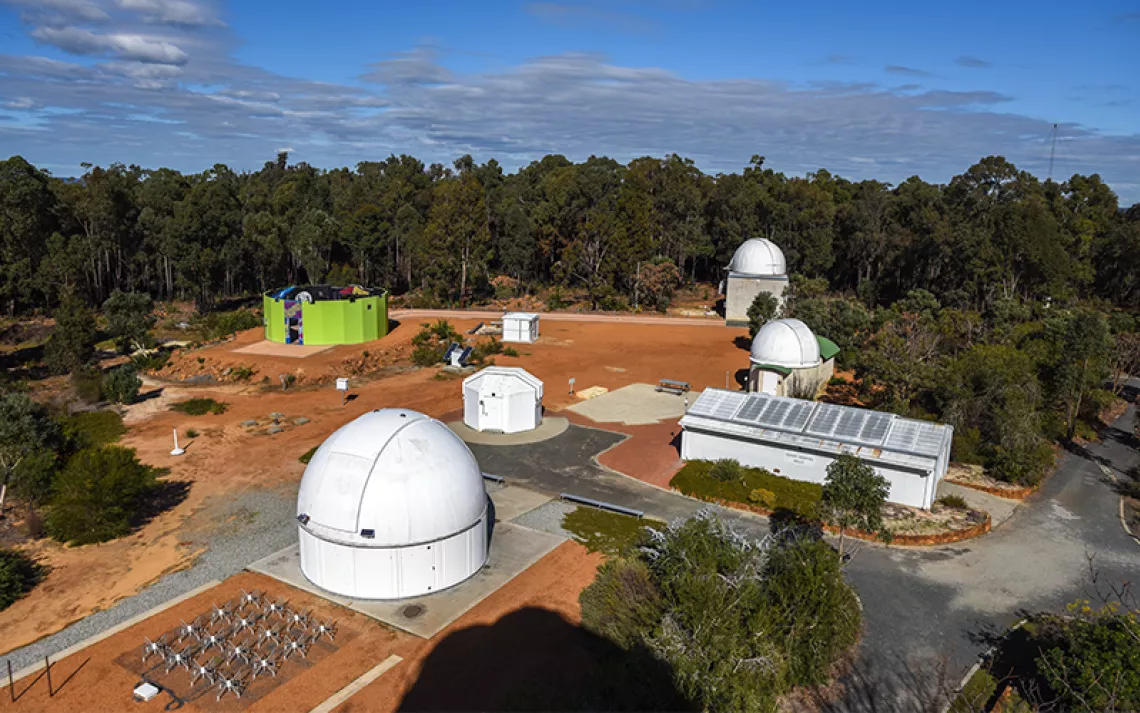

According to NASA, for many reasons. There has long been talk of building huge telescopes or space ports on the lunar surface. Because the moon has no atmosphere, the viewing would be pristine, unhampered by weather or atmospheric turbulence. Others, such as NASA administrator Jim Bridenstine, see the moon program as a prerequisite for future Mars missions—a “proving ground” where astronauts can iron out the technical kinks, but in a place that can be reached in a matter of days rather than months.

The European Space Agency has advanced the idea of creating a spaceport (something like an off-planet Grand Central Station) for traveling throughout the cosmos. In his 2020 State of the Union address, Donald Trump reiterated this idea, stating his administration’s goal of turning the moon into “a launching pad to ensure that America is the first nation to plant its flag on Mars.” (He also declared that US astronauts would be leaping and bounding across the lunar surface by 2024, though most experts feel that such a timeline is far too optimistic.)

Others have called into question the idea, stating that building moon bases introduces an unnecessarily complex step into an already technically complicated process. “Say you’ve got a bunch of new camping equipment,” said James Rice, a senior scientist at the Planetary Science Institute, to The Atlantic. “If you’re smart, you’re going to learn how to use that in your backyard. You’re not going to go, say, out to Mount Everest and try to figure out how to work this stuff.”

With all of the intellectual capital invested in these matters—scientific and political—it’s ironic that the moon has also become the source of one of the most pervasive conspiracy theories of our time: the idea that the moon landings were faked.

The origin of the moon landing conspiracy theory is often traced to a 1976 pamphlet titled We Never Went to the Moon, written by a former naval officer named Bill Kaysing. Kaysing, who worked in the late 1950s and early '60s for a company that made rocket engines for the Saturn V program, contended, among his many dubious arguments, that the iconic photographs and video from the first missions contained telling anomalies, such as a lack of stars in the background, that suggested they had been created in a studio. And what of the overwhelming physical evidence, namely the 842 pounds of moon rocks brought back by astronauts between 1969 and 1972? Kaysing asserted glibly, in a 1994 interview with Wired, that they had been fabricated in a “NASA geology lab.”

Thus it has come to pass that the brightest object in the night sky has been transformed into an object of much dimness (though Anaxogras’s persecution is a reminder that violent resistance to rationality and the hatred of facts has a long history). The moon landing conspiracy now seems like a kind of precursor to the proliferation of “alternative facts” and conspiracy theories—from the “deep state” to “Pizzagate”—that threatens to unravel our democracy. Last month the corrosive power of fallacious groupthink was on full display in Washington, DC, as a violent mob—driven mad by a conspiracy theory promulgated by the president that the election had been “stolen”—smashed through police lines and ransacked the Capitol building.

CNN reporter Elle Reeve posed a simple question to one insurgent: “What’s the point?” “What are we supposed to do, OK?” the man replied incredulously. “The Supreme Court is not helping us. No one is helping us. Only us can help us! Only we can do it!”

Nothing could open their eyes to the lack of evidence of stolen votes, nor to the clear evidence of their manipulation. Their minds were already made up. There were no Anaxograses in attendance, only true believers. To them, the president was a shining god.

WHAT TO LOOK FOR IN FEBRUARY

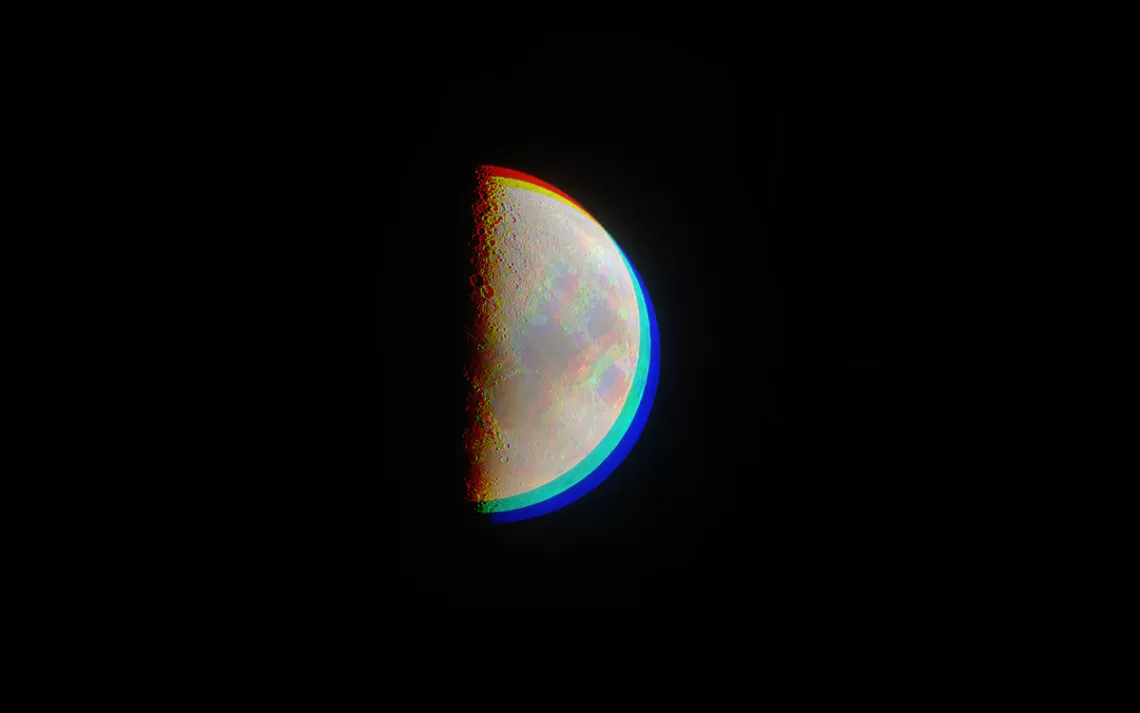

This month’s full moon, the Snow Moon, emerges in winter skies on February 27. If the sky is clear and you have binoculars or a small telescope, take the opportunity to survey the lunar surface for some of our satellite’s most striking formations.

Begin by training your gaze upon the moon’s north pole. There you will find a prominent divot, which, because of the moon’s curvature, appears strikingly three-dimensional. More than 30 miles across, this impact crater is named for the Greek astronomer Anaxogras. The crater is believed to have been formed relatively recently, since the impact “rays”—lines that extend like beams of sunlight from the core of the crater—have not been revealed by the slow process of space weathering but remain buried under layers of moon dust.

Nearly two thousand years before the advent of the telescope, Anaxogras speculated that the moon was covered in formations similar to those found on our own planet, including mountains. He was right. One of those ranges, the Apennine Mountains, curls across the moon’s upper half. Here you will find the moon’s tallest mountain is Mt. Huygens, named for the 17th-century Dutch astronomer who discovered Saturn’s largest moon, Titan. Rising to over 18,000 feet, the mountain may someday be the objective of lunar mountain climbers.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club