Fire: How Does It Even Work?

With increasing fire danger, a crash course in how to save structures

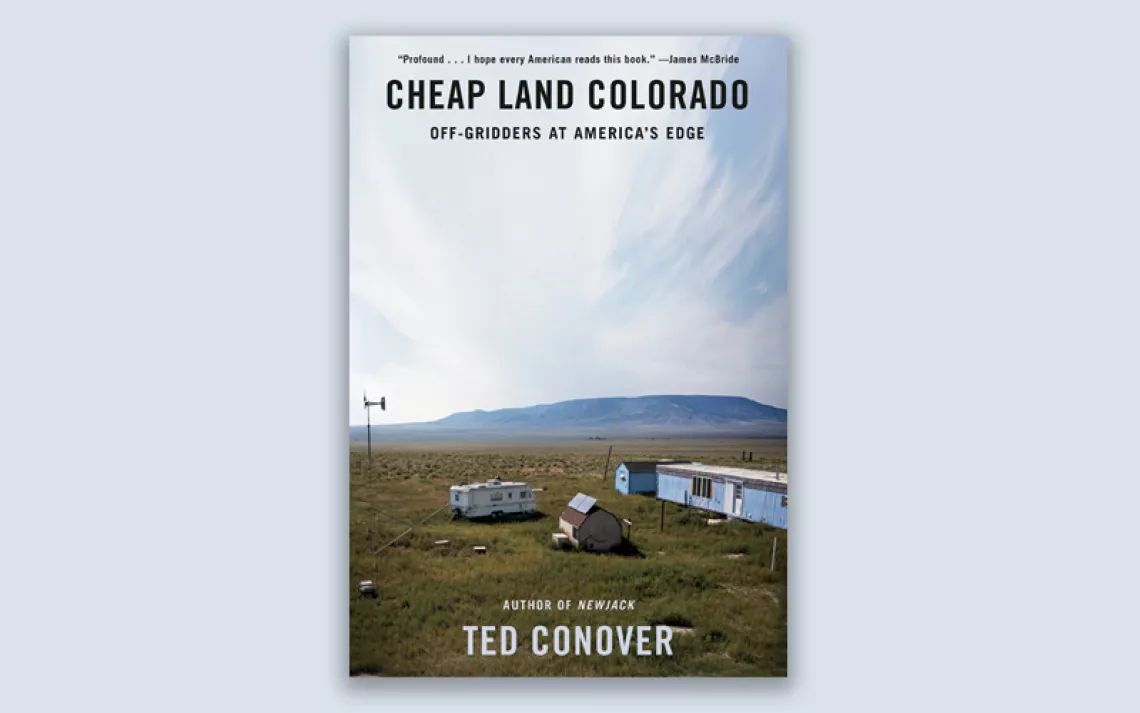

The huge wind tunnel at the Insurance Institute for Business and Home Safety can be used to test structures for vulnerability to flying embers. | Photo courtesy of IBHS

For more than a month, the Dixie Fire has been leaving a charred trail across Northern California. Now surpassing 770,000 acres, it is one of the largest wildfires in the state’s history. The burn area includes Butte County, whose residents are no strangers to record-breaking blazes: In 2018, it was the site of the Camp Fire, California’s most destructive wildfire on record. Despite burning just a fraction of the acres the Dixie Fire has consumed, the Camp Fire destroyed more than nine times the number of structures—18,804 compared with fewer than 2,000.

Researchers have identified various factors that are making wildfires grow larger and burn hotter, including the effects of climate change and forest management policies. But deciphering the proximate causes of fires’ destruction can be more challenging. A team of researchers at the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) is trying to create a framework to do just that, drawing on past fires to identify the specific factors that put developed areas at risk.

The hope is to create a yardstick for comparison, explains Alexander Maranghides, a fire protection engineer with NIST. “In Florida, you design for a hurricane category,” he says. “In Los Angeles, you have seismic requirements and you're saying, ‘OK, I'm going to design to a 7.5 on the Richter scale,’ or whatever number you choose.”

Such measures can serve as a powerful mitigation tool, allowing officials to plan and design for the unique threats their communities face. To build such a scale for wildfires, Maranghides and his team have spent the past three years pouring over every second of the Camp Fire, research they began as it was still burning in 2018. Earlier this year, the NIST engineers published an exhaustive timeline of the wildfire’s first 24 hours, with more than 2,200 observations on everything from the role of embers in furthering the fire to the response of officials, in person and remotely.

Now, they’re putting their findings to the test by crafting experiments based on the real-life incidents they studied.

For example, the NIST team cataloged the “structure ignition pathways”—the paths the fire took between buildings. Analyzing these findings, they noticed that sheds regularly contributed to the loss of homes. Having identified these structures as hazards, they are now re-creating some of the scenes they saw in Butte County in controlled settings, either using their facilities or those of the Insurance Institute for Business and Home Safety (IBHS) research facility in South Carolina, where they can conduct large-scale demonstrations of extreme weather.

IBHS research engineer Faraz Hedayati points to the facility’s wind tunnel as a particularly helpful tool—a massive room the size of four and a half basketball courts with a wall of 105 high-speed fans. Using this space, researchers can expose fires to gusty winds, mimicking real-life conditions, and then alter variables like the distance between structures, wind speeds, and the moisture content of the fuel being burned to see how that changes the flames. By making these changes, they’re hoping to identify ways to stop fires from spreading and how to use that knowledge in crafting better defensible space or home-hardening guidelines.

Another concern Maranghides says NIST noticed in its research and is now eagerly pursuing is that of burnovers—instances where flames blocked escape routes. While these are regularly recorded when they impact first-responders, Maranghides says they are not typically noted in official records when they only impact civilians. During the Camp Fire, his team identified multiple instances of burnovers threatening the lives of evacuees on emergency-designated routes, which he called a “very, very serious concern.” Since there is little comparable evidence from other fires, it’s difficult to discern how common the problem is and how much of a concern burnovers should be for other communities.

It will be years before the NIST team completes this round of research, but they’re already trying to translate what they’ve learned so far into tangible guidelines. In the Camp Fire report, they recommended a set of topics for communities to track as part of a standard framework for assessing risk, including demographics, fire history, fuels, and critical infrastructure. And Maranghides has had the opportunity to make this recommendation to top officials across the country directly, including officials within the Federal Emergency Management Agency and the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection, which is currently funding some of the NIST team’s ongoing research as part of its mitigation efforts.

“We're going to continue to have fires and never be able to get rid of having wildfires,” says staff chief Steven Hawks of Cal Fire. “But they don't necessarily have to be as destructive and as deadly as they have been.”

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club