Forest Ecologists Puzzle Out the Lessons of the Bootleg Fire

How we manage the forest will determine whether we adapt to the age of fire

Burn damage near the northwest containment line of the Bootleg Fire on July 23, 2021. | Photo by AP Photo/Nathan Howard

This spring was so dry that Marc Valens canceled plans to celebrate his 50th year on Moondance Ranch, his wooded property in Klamath County, Oregon. In hindsight, that was a prudent decision. After lightning sparked the Bootleg Fire on July 6, it grew quickly and then spread north and east, toward Valens’s ranch. At first, he wasn’t too worried. Over the years, Valens had thinned the trees from a good portion of his 300-plus acres. He had cut down and sold commercial-size lodgepole pines, then come back in and removed smaller pines where there had been “too many trees, growing too close,” with the aim of promoting aspen groves and large, old ponderosa pines.

“A Forest Service agent was pretty confident that once the fire crossed the river, it would drop down to the ground,” Valens says.

But the fire didn’t behave as predicted. The Bootleg Fire came fast and hot, destroying all the structures on Valens’s ranch, including his home and the one-room log cabin he built with college friends decades ago. In some places, the fire scorched entire stands of trees and burned down to the trees’ root systems. “They are basically saying that none of my trees are going to survive,” says Valens, who recently toured the burned parts of his property with a forest consultant.

After tearing through his ranch, the Bootleg Fire devastated Sycan Forest Estates, a woodland residential community surrounded by public land. The fire doubled every day for several days. Within two weeks, it had burned some 400,000 acres and spewed smoke across the continent, becoming the fourth-largest wildfire in Oregon history.

Harrowing reports came in from the fire line. Towering pyrocumulus clouds generated their own weather, then collapsed on themselves, strewing embers across the landscape. On July 18, the fire spawned a tornado that scattered charred trees like matchsticks. On several occasions at various locations, conditions were so dangerous that firefighters were pulled off the line and forced to retreat.

The Bootleg Fire caught even veteran firefighters off guard for its speed and intensity, especially given how early in the season it began. The megafire raises questions for forest managers, people who live in the wildland-urban interface, and anyone who is concerned about climate change and the future of Western forests. Are private landowners and public land managers thinning enough trees to reduce fuel loads? Or are we thinning too much? Should we increase our use of prescribed fire? Should state and federal firefighters put less energy into battling remote fires and instead concentrate solely on protecting human communities? Should we accept that nothing can stop some of these fires?

These aren’t just academic questions for forest ecologists. While experts debate the lessons of fires such as Bootleg, the conclusions they make will have real consequences for tens of millions of people living in the West.

The megafires of the 2020s come with staggering financial costs that now number in the billions of dollars annually, as well as increasing social costs in the form of homes destroyed, businesses disrupted, and communities displaced. There are public health costs too: Wildfire smoke drifts far beyond its point of origin, harming both fire personnel and citizens. There are also the costs to wildlife; a study published in March ties wildfires and toxic air to a devastating die-off of migratory birds last year. And, of course, there is the horrific toll in human lives lost—like the 85 people who died in Paradise, California, in 2018.

A better understanding of fire behavior will be crucial as temperatures continue to rise in the coming decades. For now, at least one lesson is abundantly clear: Climate change is driving more intense fires.

“It’s hotter earlier; it’s hotter mid-season; it’s hotter later in the year,” says Daniel Leavell, forestry agent for the Oregon State University Klamath Basin Research and Extension Center. “It’s dryer. Snow is wetter, and it melts earlier. Water evaporates sooner.”

Wildfires depend on three things—fuels, topography, and weather—says Leavell, who has spent his career both fighting and studying fire. “Once that fuel is dried out, you put the wind and the heat and the fire behind it, it will burn and it will burn hot.” Drought and a record-breaking heat wave have dried out trees, shrubs, grasses, fallen needles, twigs, and dead branches to dangerous levels.

The forests of southeast Oregon, where the Bootleg Fire occurred, regularly experienced enormous fires in the past, usually in times of drought. But the megafires of yore took place in a landscape that burned frequently, which kept fuel loads down and regulated fire intensity. Indigenous people also used frequent fire as the primary tool for stewarding lands.

Historically, forests on the east side of the Cascade Mountains have a sparser, more variable structure than the lush, dense forest west of the Cascade Range, says James Johnston, faculty research associate at Oregon State University College of Forestry. This structure ensured the forest overall could tolerate fire. Some trees would burn, but the larger, older ponderosa pines, which Johnston calls the “backbone” of dry forest ecosystems, generally survived.

This pattern changed once white settlers arrived with saws and cattle. “We saw very heavy unregulated grazing up to the 1930s,” Johnston says. Livestock removed vegetation that would have carried surface fires across the landscape. Then, starting a century ago, “we began excluding fire in the mistaken belief that fire was damaging future timber crops,” Johnston says. “To cap it all off, we logged many of the old ponderosa pines that were resistant to fire and drought.”

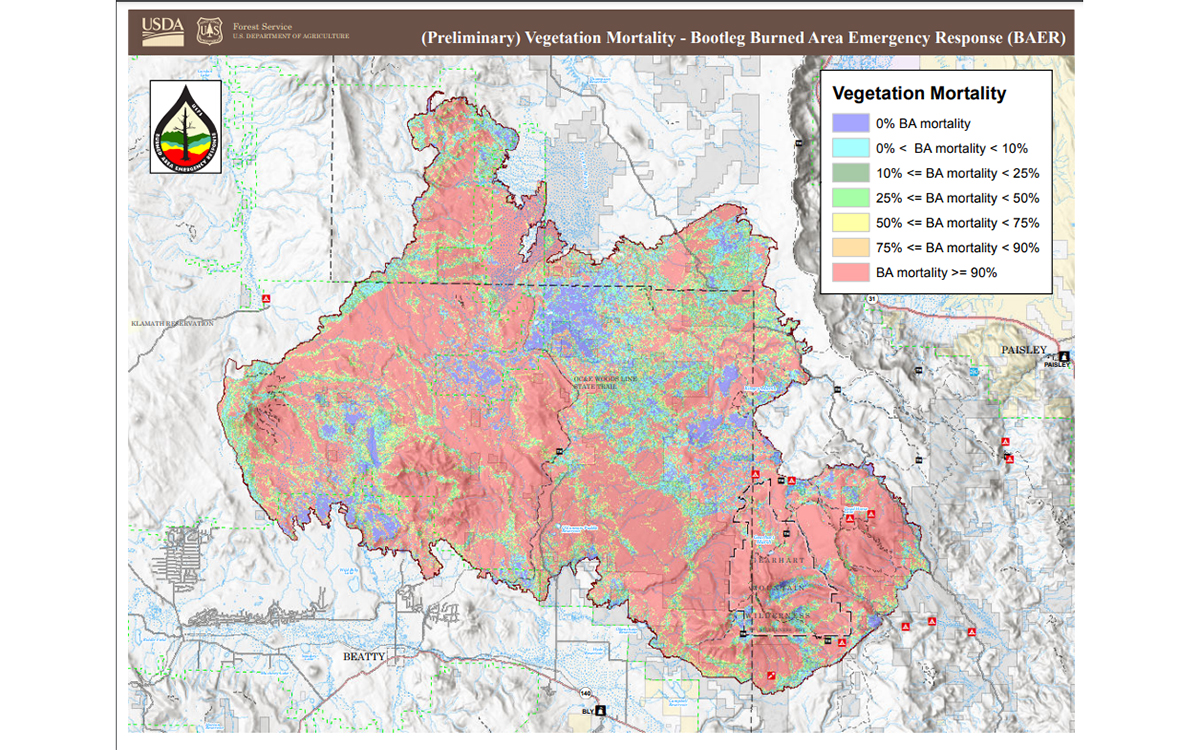

The results of 100 years of forest and fire mismanagement can be witnessed today. As the Bootleg Fire spread, Bryant Baker, a cartographer and conservation director at Los Padres ForestWatch, created a map that shows the checkered history of forest management on lands impacted by the fire.

“The reason I made the map initially is I wanted people to understand these are not unmanaged, untouched forest landscapes,” Baker says. Along with suppressing fires, “we have also been logging [forests] for the last century, to a much greater extent than people realize and understand,” he explains. The flurry of road-building and clearcutting persisted through the 1980s in many Western forests. With no fire to thin them, the landscapes filled in with smaller, shade-tolerant trees, leaving large swaths of forest that are largely homogenous—very different from the pre-settlement structure.

Commercial logging still takes place on public and private lands in Oregon, but current regulations prevent the cutting of trees over 21 inches in diameter in east-side federal forests. Today, many fire-prevention projects focus on preserving large trees and promoting a forest structure that more closely resembles pre-European settlement conditions.

Valens recalls how this shift occurred near his own land. In the 1980s, the Forest Service clearcut 40-acre plots adjacent to his property, taking only the large ponderosa pines. More recently, the Forest Service has been thinning areas near his ranch, then returning a few years later and intentionally burning it, leaving areas with large ponderosa pines and “not much else.” “We drove through some areas where I’m pretty sure a bunch of those ponderosa pines will survive,” Valens says.

Proponents of prescribed fire argue the practice offers a way to reintroduce more frequent and smaller fires to the landscape, but in a controlled way. The Klamath Tribes, for example, have been using prescribed fire to restore key areas within the Klamath Restoration Forest through an agreement with the Forest Service. The tribes have partnered with scientists to create “reconstruction plots” that map the structure and pattern of trees as it used to be.

“We took that information and applied it to the prescription or treatment plan we’d write,” says Steve Rondeau, natural resources director for the Klamath Tribes. The treatments included “mechanical thinning” and prescribed fire and provided an opportunity to revive an ancient practice among tribal members.

Two of those treatment areas were affected by the Bootleg Fire. A video filmed shortly after the fire swept through compares areas that had been treated with prescribed fire with areas that had been thinned only. In the prescribed fire area, fire had crawled partly up the trunks of some large ponderosa pines but stopped before reaching the crowns.

“A lot of the areas that just had logging didn’t fare so well,” Rondeau says in the video. “But if they had logging and prescribed fire, it was a totally different story.”

The Klamath Tribes also partner with the Nature Conservancy, which has used a combination of Western and traditional knowledge to manage the 30,000-acre Sycan Marsh Preserve, a high-elevation marsh surrounded by forest. Pete Caligiuri, Oregon forest program lead for the Nature Conservancy, calls Sycan Marsh a “living laboratory” where researchers are learning how different types of treatments—ecological thinning, prescribed burning, and a combination of the two—influence tree health, habitat, and wildfire behavior.

“Our work has been focused on taking what we’ve learned about historical forest patterns—how forests grow in a ‘gappy-patchy-clumpy’ mosaic or heterogeneous pattern,” says Caligiuri. This pattern should make the forest more resilient to fires; it also might work to promote a greater diversity of understory shrubs, flowers, and grasses, which are critical for songbirds and pollinators.

Though Caligiuri stresses that it’s too early to draw conclusions, the fire appeared to moderate its behavior once it reached areas that the Nature Conservancy had thinned and burned. The Bootleg Fire was an unplanned experiment, Caligiuri says. “Now we want to make sure we get out there and collect the right data so we can address the right questions.”

Although the use of prescribed burns is becoming more widespread, budget constraints and a lack of trained personnel have limited the practice. A bill introduced in the Senate this year and supported by the Sierra Club would “encourage and expand” the use of prescribed fire on public land, especially in the West.

Some forest ecologists, however, question the efficacy of these strategies. They argue that thinning forests in the name of fuels reduction doesn’t stop fires and that these projects unnecessarily remove large amounts of carbon from the forest. Thinning projects that leave large amounts of slash on the ground can increase wildfire risk.

“Thinning is ineffective in altering fire behavior under the hot, windy, extreme fire weather conditions that have caused the largest losses of homes and lives in recent years,” the Center for Biological Diversity wrote in a brief criticizing large-scale thinning for biomass energy production.

Baker of Los Padres ForestWatch criticizes the message he sees in too many public debates over wildfires: that if we had just managed our forests better—doing more thinning, allowing more fires to burn—we wouldn’t be in this mess. “That is an oversimplification that distracts from the fact that we have been doing a lot of intensive management in a lot of places—a lot of logging and thinning, and increasingly, prescribed burning,” he says. Yet fires like Bootleg tear through these landscapes anyway.

“For many years, we have been investing in vegetation management outside of communities in the backcountry,” Baker says. “We should put as much as we can into helping people that live in the interface directly.” This means focusing on simple, inexpensive measures that create ember-resistant buffers around homes. The vast majority of funding should go to creating fire-proof defensible space, pruning vegetation within a hundred feet of homes, providing evacuation assistance, and developing evacuation plans, Baker argues.

Leavell believes that we should focus on all fronts: inside and outside the home but also on the neighborhood and landscape scale. He lauds the Klamath Lake Forest Health Partnership (KLFHP) as an example in which state and federal agencies have worked with private landowners to identify high-priority areas for reducing fuel loads. For validation, Leavell points to the 242 Fire, which burned through parts of a large KLFHP project near Chiloquin, Oregon, in 2020. High-risk areas had been thinned and burned, and crews helped private landowners create defensible space around homes.

“The fire did what we expected it to do. The impacts were blunted,” says Leavell, adding that he is “very curious” to learn how treated areas fared in the Bootleg Fire.

As with most fires, the Bootleg Fire burned in a mosaic pattern, with patches of high, moderate, and low-intensity fire. Initial maps created by the Forest Service show large swaths where over 90 percent of the vegetation was killed. Debate will surely spring up over what—if anything—to do with all the dead trees.

While a newly charred forest looks bleak, it’s by no means wood gone to waste. Snag forests are ecologically important and surprisingly diverse. Ecologists argue that so-called salvage logging leads to decreased biodiversity, especially among creatures that depend on dead wood—for example, woodpeckers. In addition, post-fire logging can damage soils, hasten erosion, and add to carbon emissions.

These debates about how best to manage public lands often look much different for private landowners with relatively small parcels. Valens purchased his land as an idealistic 21-year-old, hoping to escape the rapid development he saw happening in Marin County, California. He plans to stay and rebuild at his beloved Moondance Ranch. But along with ashes, he is left with questions. Most urgently, he’s trying to decide whether to hire a logger to remove trees that probably aren’t going to survive.

Valens agrees that there’s an ecological argument for leaving them in place, even if they all eventually die. “But if we can make enough money by selling some of these trees to pay for replanting, that would be great,” he says.

Everyone who lives in the West is bracing for more megafires—more evacuations, more destruction, more smoky skies. With these threats also comes an opportunity to remake our relationship with fire. While the best path forward may not be entirely clear, it’s incumbent upon us to find the lessons from fires like Bootleg so that we can protect our homes, our communities, and the forests upon which so much life depends.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club