Foxes in the Henhouse: Industry Veterans Fill the EPA

Ethics groups warn that appointees may put industry ahead of public interest

Illustration by Ilbusca/istock

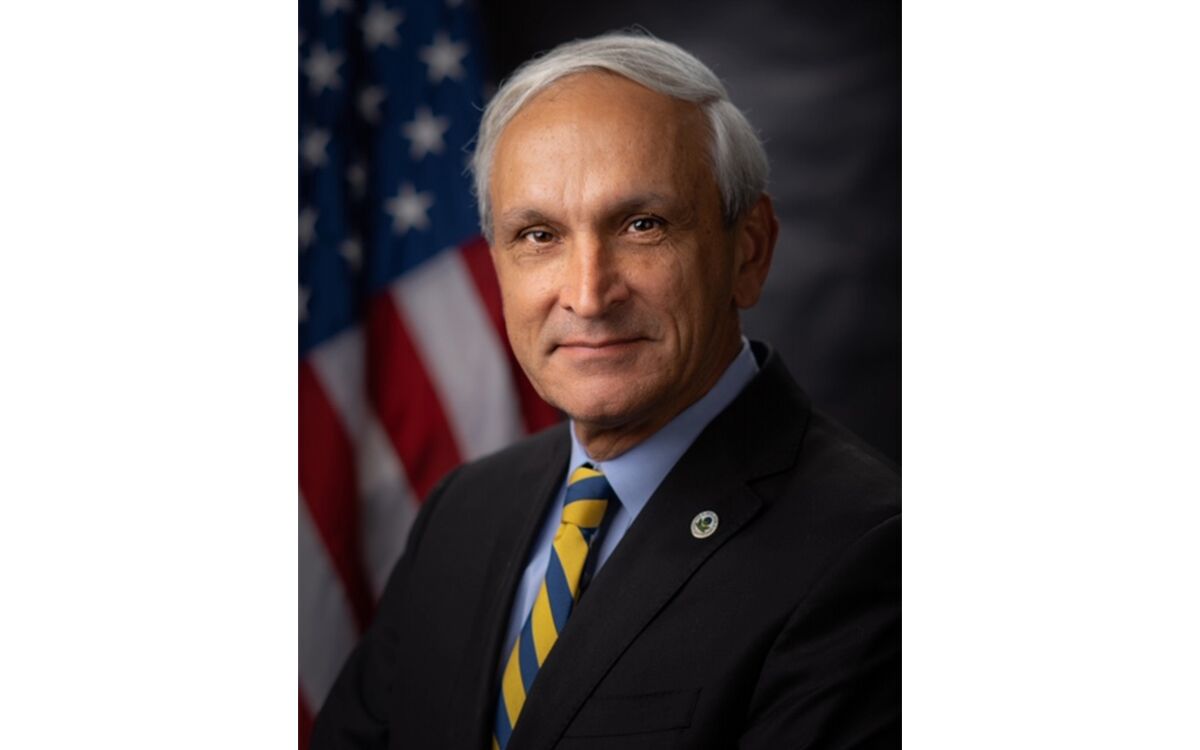

When the Environmental Protection Agency announced in August that a former fossil fuel executive would oversee environmental issues in Texas and neighboring states, the news largely flew under the national media’s radar. Watchdog groups, however, were alarmed, and they quickly expressed concern about the decision to appoint long-time oil industry insider Ken McQueen to lead the EPA’s Region 6, which is the epicenter of fossil fuel extraction in the United States.

“I think it raises legitimate questions,” said Virginia Canter, chief ethics counsel for the nonprofit, nonpartisan government-monitoring group Citizens for Responsible Ethics in Washington, or CREW.

Canter, whose organization focuses on accountability and ethics, noted that while the government has systems in place to guard against conflicts of interest, the optics of appointing McQueen send a disconcerting message. “It looks like industry will benefit,” she said, explaining that appointees from industry backgrounds might “be more likely than not to represent industry interests rather than the American people.”

McQueen’s selection fits into a broader trend for federal agencies under the Trump administration, particularly the EPA. High-profile appointees often come from industry backgrounds, only to take government positions overseeing the same sectors in which they once worked. Some later return to the private sphere, often to work as lobbyists on the issues they previously regulated.

This “revolving door” goes all the way to the top. Disgraced former EPA administrator Scott Pruitt, for example, is now working as a fossil fuel lobbyist after rolling back environmental protections while leading the agency. His replacement, Andrew Wheeler, is himself a former coal lobbyist.

While Pruitt and Wheeler are high-profile figures given their titles, some less prominent appointees, such as McQueen, are also starting to attract scrutiny.

From 2016 to 2018, McQueen, who has deep roots in the oil and gas industry, served as New Mexico’s energy secretary. He previously worked in the fossil fuel sector for more than 35 years, most recently as vice president for the Oklahoma-based WPX Energy. The company has investments in the oil-and-gas-rich Permian Basin, an area straddling Texas and New Mexico. In his new position, McQueen oversees both those states, along with Louisiana, Oklahoma, Arkansas, and the lands of 66 Native American nations.

Luke Metzger, executive director of Environment Texas, said he is “very concerned” about McQueen’s appointment. “He's had a long career in oil and gas, and then while in New Mexico proceeded to roll back environmental standards,” Metzger explained.

Metzger also noticed that EPA’s announcement of McQueen’s appointment touted his experience rolling back rules and regulations. “It didn't say anything about any results in improving environmental quality,” Metzger said.

Metzger is worried that the emphasis is an indicator of where the agency’s priorities lie in the era of President Donald Trump. Having a figure so close to the fossil fuel industry overseeing Region 6 could give oil and gas companies an advantage over wind and solar competitors, he fears, and in the process set back efforts to accelerate the transition to a clean energy economy.

Ken McQueen | Photo courtesy of US EPA

Ken McQueen | Photo courtesy of US EPA

McQueen has shied away from addressing climate change, which he called "just part of the history of the world we live in” during the confirmation hearings for his prior New Mexico position. While he revised that view in an August 2019 interview with the legal publication Law360, critics remain worried that McQueen will not prioritize combating global warming.

In addition to McQueen, another controversial figure is former Dow Chemical lobbyist Dennis Deziel, who now oversees EPA Region 1, which encompasses the New England states of Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Connecticut, along with the territories of 10 Native American nations. The region is home to a number of Superfund sites—areas so deeply contaminated by toxins that they have been singled out for cleanup by the government. Many are polluted as a direct result of industrial activity.

One company that is often in the subject of Superfund cleanups is Dow, Deziel’s former employer. Dow has a long history of environmental scandals, including concealing documents from the government after dioxin contamination in Michigan sparked a 2003 lawsuit.

Deziel has argued that his experience dealing with the industry side of chemical contamination makes him qualified for his current role. But some watchdog groups say Deziel’s prior work has some alarming overlap with his current portfolio. According to the nonpartisan Center for Responsive Politics, Deziel has done significant lobbying for Dow on environmental and Superfund issues. Dan Auble, a senior researcher with CRP, explained that lobbying records on specific issues can be hard to pinpoint, but that filings clearly lay out components of Deziel’s former position.

“Since we don't get a breakdown of how much [time, money, and effort] he spent on each issue, it is difficult to say what he spent the majority on,” Auble said. “But ‘Environment & Superfund’ showed up . . . on more filings than the others since 2014.”

Deziel isn’t the only former Dow employee with control over Superfund sites. Former Dow attorney Peter Wright is now leading the EPA’s waste and Superfund cleanup office, even after Senate Democrats sought to block his nomination in July.

Wright once described himself as Dow’s “dioxin lawyer” and worked on behalf of the company as it dealt with the EPA over Superfund issues. Wright has recused himself from some 300 Superfund and hazardous waste sites that involve his former employer, but ethics experts like CREW’s Canter still have concerns.

“Any time you've got former industry members . . . in important positions, heading important regions, it raises the question of whether or not they're [acting in] the public's best interests in terms of protecting the environment, or just continuing to represent their industry,” she said.

Such conflicts of interest have already led to the downfall of one EPA insider. Bill Wehrum, the former head of the EPA’s office of air and radiation, lobbied on behalf of major chemical companies before joining the government. He resigned from the EPA in June, just as the House Energy and Commerce Committee opened an investigation into whether Wehrum had used his position at the agency to help former clients.

Wehrum’s successor, Anne Idsal, has spent her career in government working on land and environmental issues. But Idsal, who comes from a wealthy Texas Republican family, has maintained close ties with the oil and gas industry despite her work, leading to ethics concerns. Idsal preceded McQueen as head of Region 6 under the Trump administration, and her stance on climate change echoes industry talking points. In a 2017 interview with the Texas Observer, Idsal argued that there is “still a lot of ongoing science” about global warming, and that “climate has been changing since the dawn of time, well before humans ever inhabited the earth.”

Given her role overseeing air and radiation policy, Idsal’s views and her ties to fossil fuel executives could have significant implications for federal climate action. Along with McQueen, Deziel, Wright, and other officials, Idsal is helping to shape government environmental policy, likely with input from industry stakeholders.

Environmental and public interest watchdogs worry that the close relationships between federal officials and corporations are fraught with conflicts of interest and have spurred the sweeping rollbacks on environmental and public health standards. “They're implementing policy on a day-to-day basis . . . [their industry ties] are going to have a direct impact,” said Canter, who underscored that such political appointees are only heightening fears about the influence of private-sector corporations on the Trump administration.

In January 2017, immediately after his inauguration as president, Trump ordered federal agencies to reduce their costs by scaling back regulations. The White House mandated that for every new rule issued, two other rules would have to be scrapped. According to an August 2019 report from the EPA’s Office of Inspector General, the agency “exceeded” that executive order by a wide margin in 2017 and 2018. After issuing only four new regulations during that time, the EPA cut 26. "[T]he EPA had the highest number of deregulatory actions of any federal agency," the report observed.

Given such aggressive rollbacks, Canter offered a grim warning about the corporate infiltration of the Trump administration’s EPA: “It looks to me like an industry takeover.”

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club