Free Shipping Isn’t Free for Everyone

Online retailing delivers a public health problem

Warehouses in San Bernardino Transit Pictures

Free Shipping Isn’t Free for Everyone

Online retailing delivers a public health problem

Story by Judith Lewis Mernit

Produced by Geoff McGhee

I. When Truck Season Became All-Year-Round

When Angelo Logan was growing up in the City of Commerce, California, in the mid-1980s, there was a time of the year that he and his friends called “truck season.”

“It was the two or three months leading up to the holidays,” he remembers. During truck season, semitrailers loaded up at the Ports of Long Beach and Los Angeles, unloaded their goods at storage facilities, and transported them to local department stores.

BNSF Rail Yard in San Bernardino Transit Pictures

As warehousing expanded in the region, so did truck season. Commerce was an ideal hub, centrally located among railyards, highways, and maritime ports—and the trucks began to come and go all year long. But traffic was still limited to certain times of day. “It used to be that we’d see drayage trucks coming from the ports to the warehouses and railyards in the early morning. Then at a certain time at night, you’d see transloading trucks that would go from the warehouses to the railyards.”

Tara Pixley

Tara Pixley

Now, Logan says, “the types of trucks and operations are constant.”

“You’re seeing it, you’re hearing it, but you’re also breathing it,” Logan says of the diesel exhaust. “The only relief you get is a change in the direction of the wind.”

— ANGELO LOGAN, Moving Forward Network and resident of Commerce, CA

Angelo Logan in Commerce, California, in June.

Tara Pixley

II. E-Commerce, in Real Life

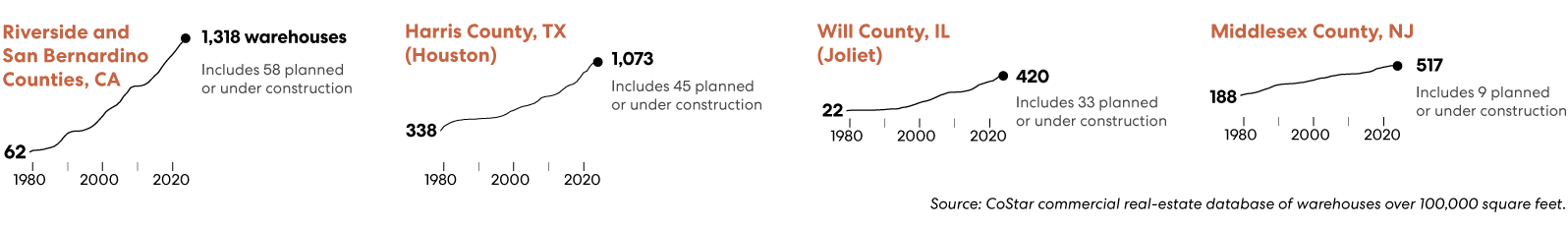

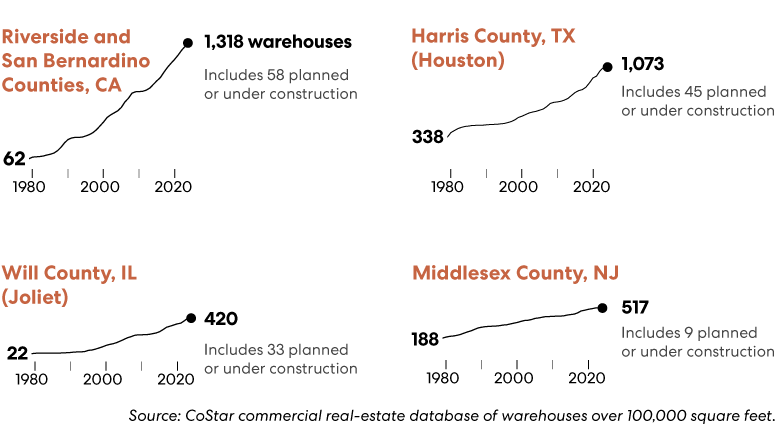

Southern California’s mushroom-like spread of mega warehouses (facilities that are 100,000 square feet and larger) and the accompanying heavy truck traffic and air pollution is a harbinger of what’s coming to the rest of the country.

The explosion of online shopping has led to a frenzy of warehouse construction in almost every region of the United States. To accommodate the flow of merchandise, Amazon and other online retailers have built what they call “fulfillment centers” in key hubs where zoning is welcoming (or nonexistent) and land is cheap.

Warehouse growth in square footage since 1980

Although the warehouse buildout began before COVID isolation prompted many people to rely on home delivery, e-commerce skyrocketed during the pandemic.

Amazon’s product sales revenue grew from $160 billion in 2019 to $241 billion in 2021, and during that time the company doubled its warehouse capacity. By the end of 2021, Amazon had 253 giant fulfillment centers spread across the county, along with 110 smaller sortation centers and 467 “last mile” delivery stations.

While Amazon is the largest online retailer, it is not alone.

The real estate investment management firm CBRE Group reports that in 2021, more than 1 billion square feet of warehouse space was constructed or newly leased. The firm projects that at least another 850 million square feet will be added in 2022.

Online retailers prefer to build warehouses in areas with easy access to transportation and loose development rules. This frequently draws them to areas already heavily developed for industry and often with a history of being redlined—the only neighborhoods where people of color could easily buy property in the years when covenant laws kept them out of other, more desirable neighborhoods.

Those same areas play host to sprawling, churning delivery hubs that have turned already-burdened neighborhoods into vortexes of traffic and pollution.

A logistics hub in Southern California's Inland Empire. Tara Pixley

In Southern California’s Inland Empire, massive warehouses push up against bedroom-community homes. In New York City’s Red Hook neighborhood, a sprawling UPS facility is under construction right next to apartment blocks.

For residents in these places and many others, the arrival of the mega warehouses means that traffic noise and pollution bombard them at all times of the day, all year.

“You have the warehousing, the transloading. You have the fulfillment centers—you know, these are all parts and pieces to the development of warehousing,” Logan says.

The online purchase you made the other day may seem cheap and easy, but it’s not exactly free. Someone, somewhere, is paying the price for the convenience of that one-click purchase.

III. Truck Traffic Equals Air Pollution

Last spring, Kim Gaddy, founder of the South Ward Environmental Alliance in Newark, partnered with the Ironbound Community Corporation for a two-day truck count and air-monitoring project. Ten years ago, the truck count at the intersection of Newark’s Empire and Frelinghuysen Streets was roughly 500 trucks per day.

Time-lapse videos shot in parts of Newark’s Ironbound section and the Port of Newark in August 2022. Michael Competielle

By 2022, as many as 500 trucks were passing through that same intersection in a single hour.

In Will County, Illinois (a major e-commerce distribution hub outside of Chicago), residents who live within a half mile of a warehouse have elevated rates of asthma and other respiratory diseases due to soot in the air, which is more than one-third higher than the national average and worse than in 88 percent of the country.

In Texas, 79 percent of the state’s 3,929 warehouses are in similarly polluted areas.

The Houston neighborhood of Pleasantville is ringed with major roadways that connect Houston’s port, warehouses, and last-mile facilities. Diesel tractor trailers rumble along and idle on neighborhood streets on their way from warehouses to the port.

“We were already inundated with trucks in and around our community,” says Bridgette Murray, founder of Achieving Community Tasks Successfully, a nonprofit group that works on environmental and social justice.

“Warehouses have contributed more.”

Bridgette Murray Marie D. De Jesus

The inky black cloud of diesel exhaust from heavy trucks carries fine particulate matter, also called PM 2.5. It is known to cause cancer, respiratory disease, and heart failure.

The diesel exhaust from heavy trucks also produces nitrogen oxides. When released into the air and hit by sunlight, they are transformed into ground-level ozone, the primary lung irritant in smog.

Marie D. De Jesus

Marie D. De Jesus

Marie D. De Jesus

V. E-Commerce Warehouses Are Everywhere—But Not Everyone Is Impacted Equally

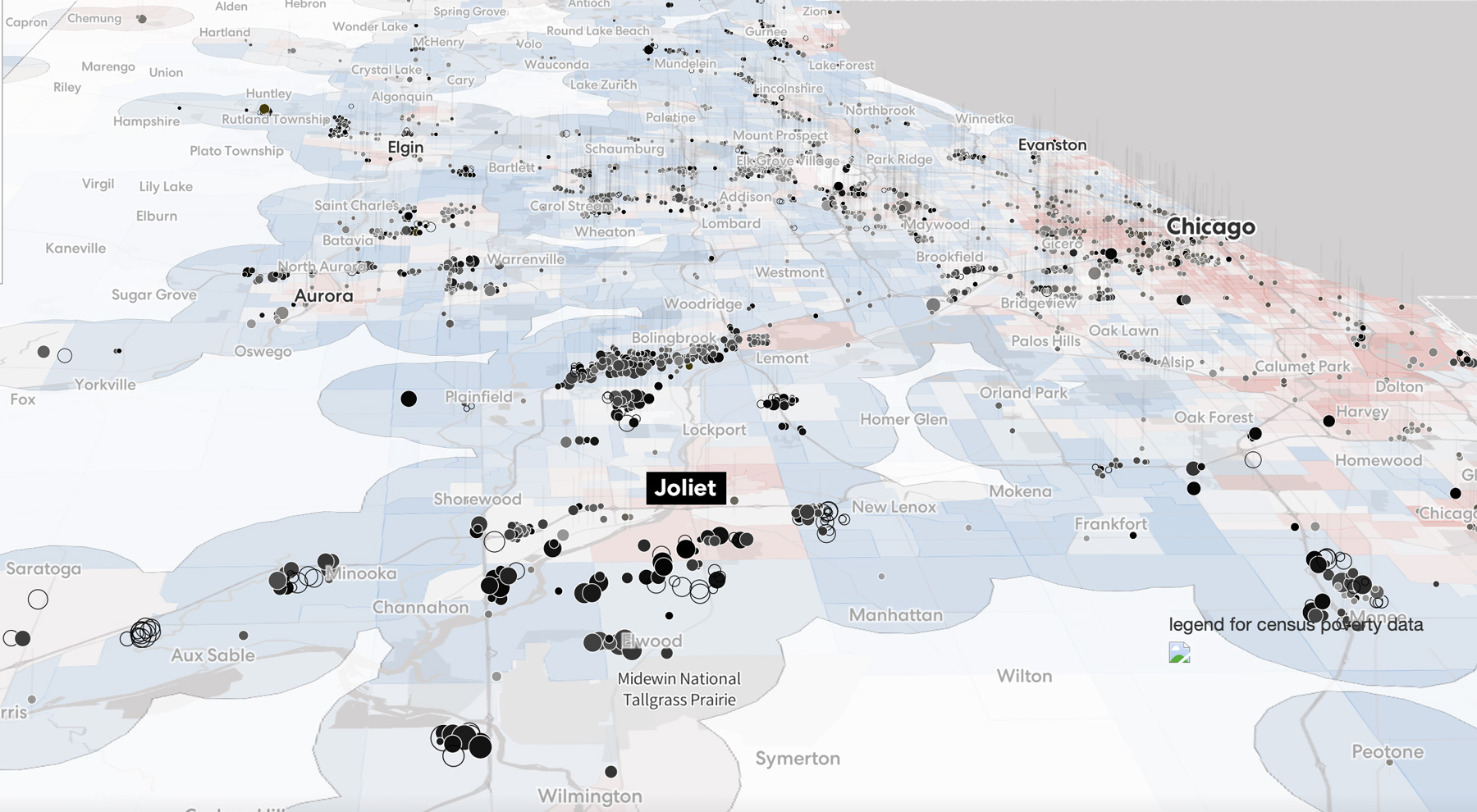

Today in the United States, there are 39,116 warehouses and distribution centers larger than 100,000 square feet, and they can be found in rural and suburban areas as well as urban ones.

Article continues below map. Scroll, click or tap twice to resume..

Tap to advance.

But not everyone is impacted equally by the explosion of e-commerce. Often, the consequences fall hardest on communities of color.

A research project by the Environmental Defense Fund mapped 60 intermodal and warehouse facilities in the Houston-Galveston area and found that almost all were located within a mile of vulnerable communities, whose residents are predominantly people of color.

Port of Houston Shareef Wright

A Sierra Club analysis found that 79 percent of the population within a half mile of the Houston metro area’s 1,186 warehouses are people of color.

Residents of Pleasantville, a heavily industrialized neighborhood of Houston where most of the residents are Black, believe that official estimates don’t capture the full brunt of toxic emissions in their community. The EPA measures pollutants in the atmosphere over a broad area, based on 12- or 24-hour averages.

Environmental justice advocates say that process fails to measure pollution spikes that occur at various times of the day or night and also blurs the lines between cleaner-air communities and heavily burdened ones.

“Pleasantville is right at the intersection of Interstate 10 and Highway 610, which is a major route from the port. It was one of the few places where Black people could buy a home, so we are a predominantly Black community.”

— CYRUS CORMIER, Houston resident

Cyrus Cormier near his home in the Pleasantville neighborhood.

Marie D. De Jesus

“Because of our proximity to the Port of Houston, a lot of the warehouse traffic comes through here.”

Morning traffic on Houston's East Loop Freeway.

Marie D. De Jesus

“Our community is in the top 90th to 95th percentile for diesel particulate matter, the 80th to 90th percentiles for asthma rates. It's in the 95th percentile for low life expectancy, the top 90th to 100th for heart disease when you compare it to the rest of the nation.”

A street in the Pleasantville neighborhood of Houston.

Marie D. De Jesus

“In terms of diesel emissions, there are so many possible solutions. The first one is to address truck idling. With all of these warehouses, there comes a lot of trucks waiting to pick up goods for delivery. While we do have an ordinance in the Houston area against idling, nobody is following that ordinance at all.

In a year’s time, they’ve only looked into one complaint. And the way the ordinance reads is there are 100 different ways that the driver or company can get out of being ticketed.”

A truck yard in Houston.

Marie D. De Jesus

IV. What Diesel Exhaust Does to the Human Body

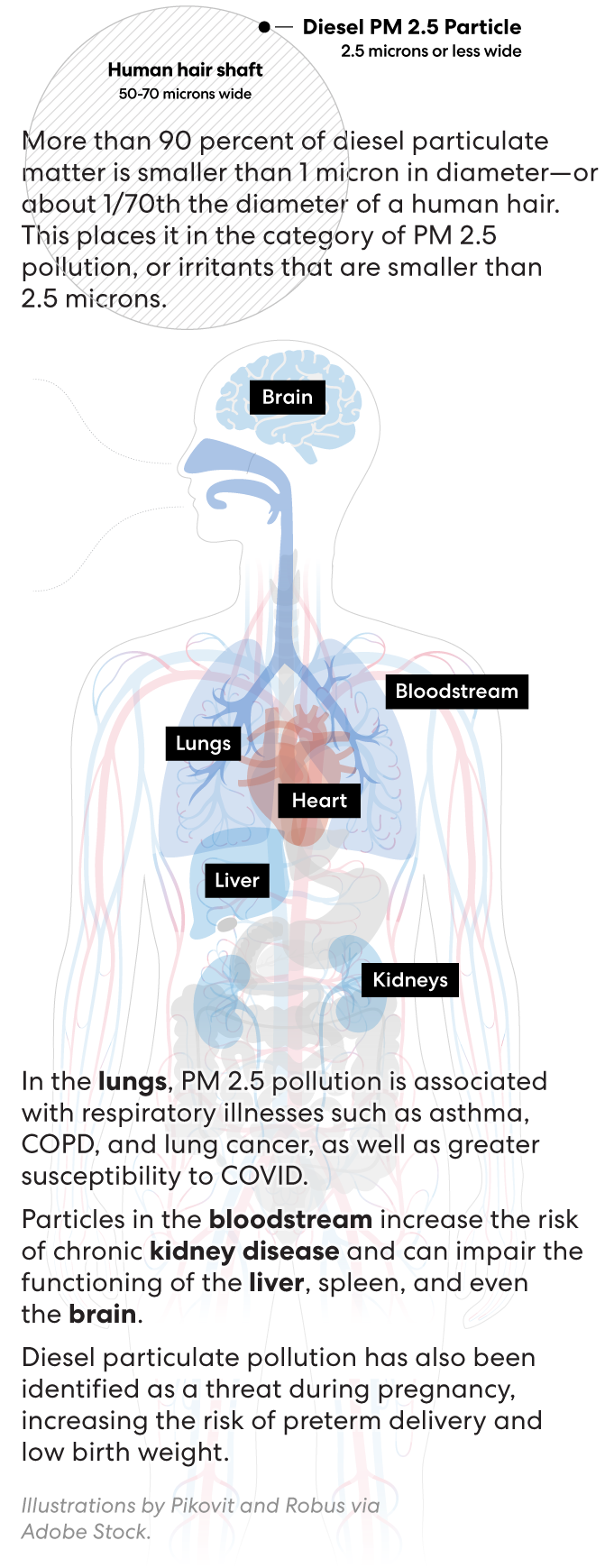

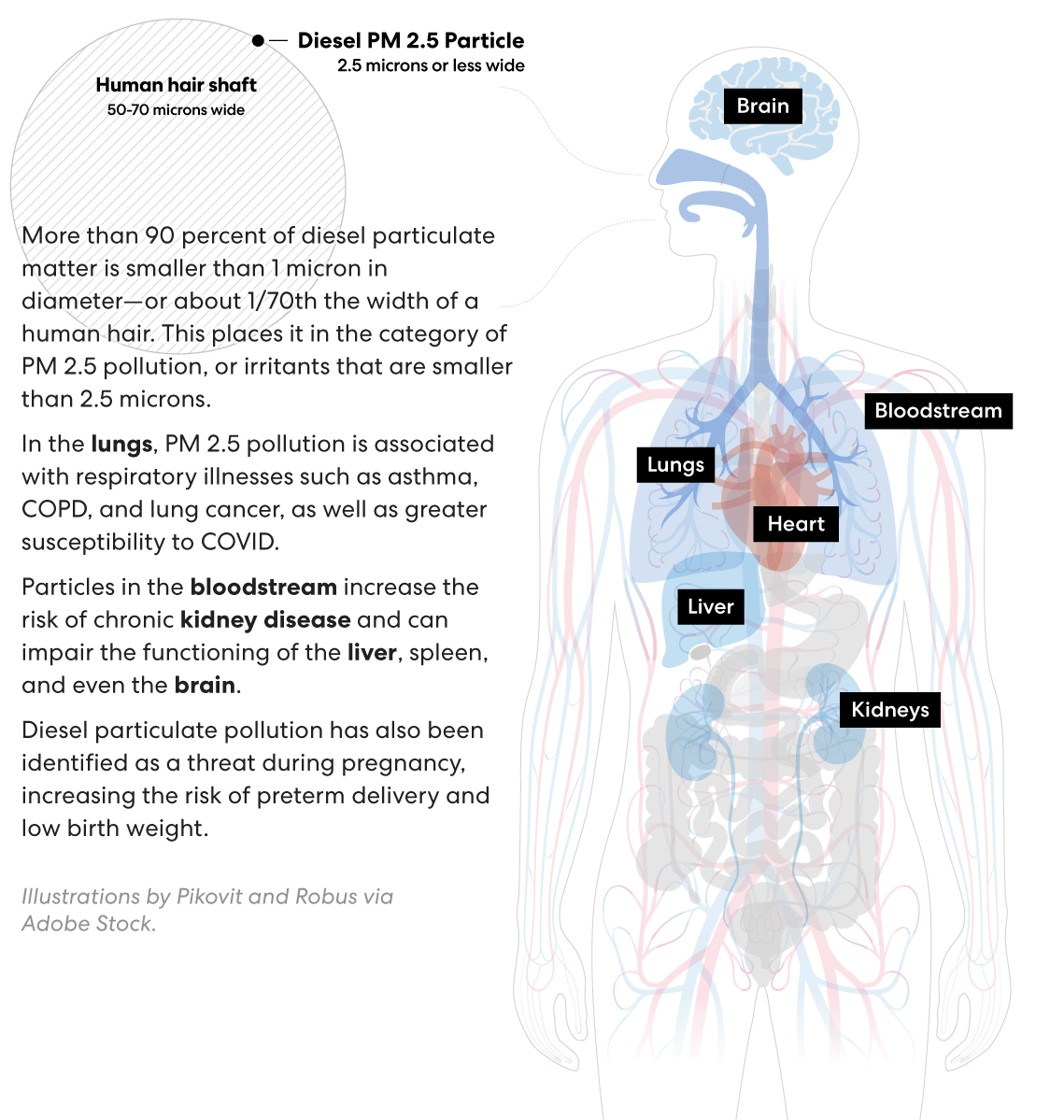

The pollution you don't see in diesel exhaust is more dangerous than the soot you do see.

Diesel particulate matter is so small that it can easily enter human airways, penetrate tissue, and embed in the lungs. If those particles penetrate the alveoli—the tiny sacs that take in oxygen and release carbon dioxide—and make their way into the bloodstream, they can damage the heart and other organs.

PM 2.5 and the Body

An Aerial Assault on Multiple Organs

Particulate matter isn’t made up of any one chemical or compound. It is instead a “mixture of mixtures,” in the words of the EPA.

The tiny irritants can carry anything from pesticides to heavy metals to benzene, a carcinogenic hydrocarbon present in diesel exhaust. Particulate matter has been implicated in heart disease. Because it infiltrates the bloodstream, it increases the risk of developing chronic kidney disease and can impair the functioning of the liver, spleen, and even the brain.

Most of all, it causes or aggravates a whole host of respiratory illnesses in children and adults: asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, lung cancer, and COVID.

The smaller the particle, the more dangerous its effects.

VI. Workers Suffer Too

A toddler at a playground located next to a warehouse distribution center. Sebastián Hidalgo

Warehousing is nothing new to Chicagoland, that region that spreads from the southwestern shores of Lake Michigan north to southern Wisconsin and east into Indiana.

Five of the seven railroads in the nation intersect in Illinois’s Will County, which is a one-day drive from 60 percent of the United States mainland and home to the country’s largest inland port. At last count, 370 warehouses larger than 100,000 square feet occupied the county, with another 64 proposed or under construction.

The corporations and developers behind the warehouse boom, including the multibillion-dollar landlords Prologis and Blackstone, have promised economic revival for cities depressed by the loss of manufacturing. But the communities themselves have felt little of the benefit.

The hourly pay for warehouse workers rarely rises to a livable wage. According to a survey conducted during the height of the COVID pandemic by Warehouse Workers for Justice, only half of workers in the food distribution and logistics sector had any health insurance.

A cement manufacturing site in the industrial area of Joliet, Illinois. Sebastián Hidalgo

Near the entrance to NRG Joliet Generating Station, a gas-fired power plant. Sebastián Hidalgo

“We also found they were uniquely affected by COVID,” says WWJ’s former labor and environmental justice director, Yana Kalmyka. Not only were people who breathe in diesel pollution day and night predisposed to the worst effects of the disease, but also they couldn’t work from home.

There are unavoidable on-the-job hazards. Dust builds up inside warehouses, “so workers are experiencing poor air quality both inside the workplace and outside when they leave,” Kalmyka notes. Many warehouse workers reside in the same communities where they work, she says, “so they’re experiencing a double jeopardy exposure to diesel pollution.” Most of those workers are Black or Latino.

“My neighborhood stinks. People will come over and they’ll be like, ‘What’s that smell?’ And I’ll say, ‘It’s the pollution from the trucks.’ They can’t believe it. And I’m not even living that close to any of the Amazon warehouses. But even so, the trucks still go by all day long, up and down the street.”

— ANGELA ORTIZ, a logistics worker and resident of Joliet, Illinois

Angela Ortiz at the industrial corridor in Joliet.

Sebastián Hidalgo

“I'm 28 years old, and I've been working in warehouses since my first job, when I was 17. I worked in an Amazon warehouse in Joliet from when they first opened in 2016. I worked there for about a year before I quit, then I went back a couple of times as a temp, until 2018. As time went on, we realized that the company may not have the community's best interests in mind—particularly, of course, the environment.”

Sebastián Hidalgo

“I know that a lot of the residents living closer to the warehouses have asthma. I used to drive Uber, and I would pick up a lot of people who resided in those areas, and some of them would go to work at Amazon or any of those surrounding warehouses.”

Ortiz overlooking a cement plant in Joliet.

Sebastián Hidalgo

“And a lot of them would tell me that they had respiratory issues, or that their kids did. I did see that a lot with my coworkers who lived in the same neighborhood as the warehouse, they would have to carry around an inhaler. It just was like everyone had asthma.”

Sebastián Hidalgo

“I think that we aren't going to get rid of the warehouses. I would just like to bring more awareness to the community about them, to create better working environments. I would also like to figure out a way that we don't have so much traffic in the area.”

Ortiz at one of her favorite places, the Pilcher Park Nature Center.

Sebastián Hidalgo

VII. How Can We Solve This?

E-commerce is likely here to stay, so reducing its environmental and public health impacts centers on fixing the operations of all those trucks. Doing so would also have a major climate benefit, since transportation (including the shipping of goods) is the number one source of US greenhouse gas emissions.

In March 2022, the EPA proposed a rule to reduce truck pollution beginning in 2027. But most clean-transportation advocates argue that the rule should be stronger. “It’s just an update to a previous regulation that says manufacturers need to be cleaning up trucks,” says Katherine Garcia, director of the Sierra Club’s Clean Transportation for All campaign. “The regulations haven’t been updated in 20 years.”

Marie D. De Jesus

Marie D. De Jesus

Transit Pictures

The EPA is expected to deliver a more stringent truck-pollution standard later in the year. In the meantime, reforms from state, county, and municipal leaders could help to clean up this logistical nightmare.

It would also help to change local zoning ordinances so warehouses can’t be located near or within neighborhoods where people live and where children attend school.

“So we want to start our own anti-idling campaign, which involves educating drivers and companies about the benefits of refraining from idling, not only how to reduce emissions but also save the companies money.”

— CYRUS CORMIER

Marie D. De Jesus

Cyrus Cormier Marie D. De Jesus

“The next thing is policy. Policy has to change in regard to industry and proximity to neighborhoods. Even though there's no zoning, at some point, somebody in the political sphere has got to say, ‘You know what? In these at-risk neighborhoods, we are not going to allow another company to come in. We're just not.’”

“It comes to a point that we just have to hold the line and make sure that industry policies and politicians don't just totally eradicate Pleasantville. I feel that something greater than myself is pushing me to engage in environmental justice.”

“With my mother living here, my cousins living here, my friends living here, I know we gotta fight. And so Cyrus has his boxing gloves on.”

One of the best long-term solutions is to electrify the fleet of long-haul and heavy-duty trucks so they aren’t releasing any local emissions at all. Electric-truck technology is “light-years ahead” of federal and most states’ requirements, says the Sierra Club’s Garcia. Since trucks dedicated to moving goods from ports to warehouses rarely travel longer than 100 miles per day, they’re ideal for electrification.

Six states—Massachusetts, New Jersey, Washington, Oregon, New York, and Maine—have already adopted California’s 2020 Advanced Clean Trucks rule, which requires that medium-to-heavy-duty trucks sold in the state get progressively cleaner over time, beginning in 2024. By 2035, 75 percent of trucks on the heavier end of the scale will have to run on electricity or an emission-free fuel. Several more states, including Colorado and Illinois, are considering following suit.

But the warehouse takeover of vulnerable communities won’t be ameliorated by laws and policy levers alone. “It’s not going to be solved just by public health specialists. It's not going to be solved just by engineers. It's not going to be solved just by the communities themselves,” says Nemmi Cole, a researcher at the University of Southern California’s Keck School of Medicine.

Bad air, wherever it comes from, doesn’t stay put—the emissions that damage warehouse neighbors’ bodies are part and parcel of those that heat up the planet. Global warming aside, Cole says, “Think about it: What if that was your child, your mother, your aunt, living along that transportation corridor from the port to the warehouse? What if one of the premature deaths policymakers attribute to pollution was your child?”

We need to understand the public health injuries of e-commerce “on a macro level,” Cole says, as if they’re hurting all of us.

Because, in fact, they are.

Get Involved

Join the movement for cleaner trucks and help to clean up this logistical nightmare.

Study Methodology

Sierra Club analysts obtained from the real estate information firm CoStar a nationwide list of existing and proposed locations categorized as “warehouse,” “distribution,” “light distribution,” and “refrigeration/cold storage,” with “rentable building area” over 100,000 square feet. Our analysts then used the US EPA’s EJScreen Mapping Tool to overlay demographic information about residents living within a half mile of the warehouses and distribution centers. The analysts queried ambient concentration of PM 2.5 air pollution, National Air Toxics Assessment diesel particulate matter exposure, and total population as well as the percentage of residents who are people of color or low income, provided by the US Census Bureau’s 2013–2017 American Community Survey.

Judith Lewis Mernit is a frequent contributor to Sierra. She lives in Kingston, New York.

More articles by this authorGeoff McGhee focuses on multimedia storytelling and information visualization. He previously worked at ABC News, The New York Times and France’s Le Monde, and was the lead writer for National Geographic’s Data Points blog. Learn more: https://www.geoffmcghee.com.

- Keywords:

- transportation

- climate change

- air

- toxics

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club