Free the Whales

Drones are helping response teams to safely disentangle whales caught in fishing lines and buoys

Photos by Andy Dietrick (NOAAMMHSRP permit # 18786-03)

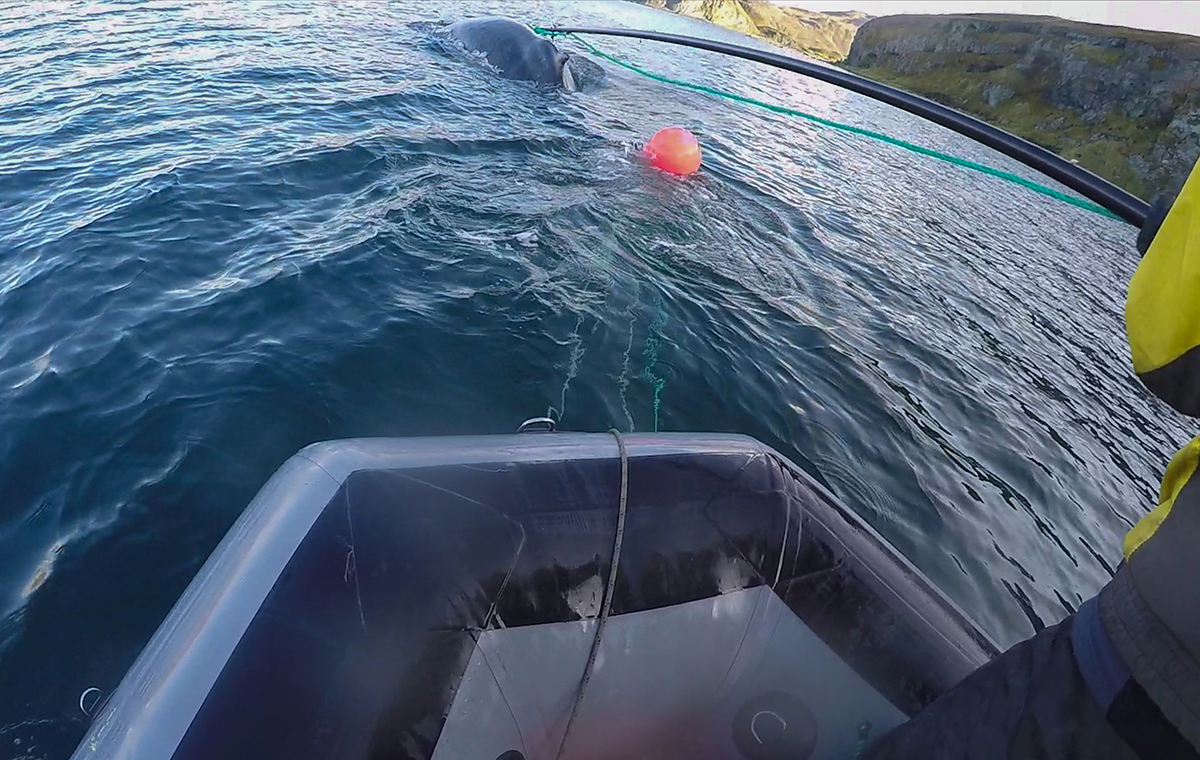

On the afternoon of Thursday, October 18, Andy Dietrick stood on the deck of Tidebreaker as he piloted a drone over the waters of the Bering Sea’s Unalaska Bay. As the drone hovered above the swells, a shadow rose from the depths; a few seconds later, a humpback whale surfaced. But something was terribly wrong.

“It was clearly ‘tacoed’,” says Dietrick, a freelance photographer and volunteer marine mammal first responder. Heavy-gauge fishing lines bound the whale’s head to its tail; several wraps encircled its flukes. The whale moved sluggishly, as if something were dragging it down.

A few days earlier, a marine biologist had spotted the distressed whale from a bluff on Unalaska Island, which is part of Alaska’s Aleutian Island chain, and had then alerted Dietrick and other local whale champions. Using his drone, Dietrick was then able to capture video footage of the whale as it surfaced every two to three minutes. That evening, he sent the footage to officials at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) so they could study the situation and come up with a plan to safely cut away the lines. Without human intervention, the animal would likely die.

According to the International Whaling Commission, an estimated 300,000 whales and dolphins die every year from entanglements. Though fishing gear—lines, nets, crab pots, and the like—is often the culprit, weather buoys, cruise ship anchors, and marine debris can also snag marine mammals. Sometimes, entanglement means instant death by drowning. In many cases, whales can drag gear wrapped around their bodies for months, or even years. Some slowly starve. Others develop deadly infections at the points where lines cut into their flesh.

Under the Marine Mammal Protection Act, NOAA Fisheries’ Office of Protected Resources is charged with coordinating emergency response efforts to entangled and stranded marine mammals. But volunteer networks, operating under NOAA permits, are often the first to mobilize a rescue effort when a report of an entangled whale comes in. (In Canada, Fisheries and Oceans oversees response networks.) Using techniques borrowed from the whaling industry, a trained team approaches the entangled cetacean in a small inflatable boat, backed by one or two support vessels and land-based crew. But the rescuers must get close enough to evaluate the problem. And that’s where drones come in.

NOAAMMHSRP permit # 18786-03

NOAAMMHSRP permit # 18786-03

Unmanned aerial vehicles (or UAVs) are the newest tool in a whale entanglement response team’s toolbox. Small, light, maneuverable, and relatively inexpensive, UAVs have become an important instrument in assessing a whale’s predicament and preparing for a disentanglement attempt. But flying a drone on land and piloting one from a vessel in turbulent seas while attempting to get close—but not too close—to a distressed, 40-ton animal is tricky business.

So Brian Taggart and Matt Pickett from the marine conservation nonprofit Oceans Unmanned launched the freeFLY initiative in order to give special training to pilots already familiar with UAVs. Taggart and Pickett provide a combination of classroom training and practical exercises during which their trainees practice launching and recovering drones from vessels, communicating with crews, and maneuvering over whales. The Chinese drone manufacturer DJI has donated its Phantom 4 and Mavic drones to the program, while DARTdrones, a UAV instruction company, has provided complimentary online test prep materials. To qualify for the freeFLY training, pilots must already have their remote pilot license from the Federal Aviation Administration.

“Anyone with a thousand dollars can buy a drone today,” Taggart says. “We have to offer something above and beyond just the technology itself.” That something is expertise. Taggart and Pickett are both retired captains with NOAA. They formed the nonprofit Oceans Unmanned two years ago with the goal of supporting environmental research with drones. In addition to freeFLY, they’ve helped a team at Oregon State University explore the efficacy of drones in finding marbled murrelet nests and surveyed a gray seal colony on Muskeget Island, near Nantucket, Massachusetts. The pair also created EcoDrone, an initiative to encourage recreational drone fliers to adopt best practices that limit disturbance to wildlife.

While with NOAA, Pickett had helped colleague Ed Lyman acquire manned aircraft to help with entanglement responses. Lyman is the Large Whale Entanglement Response Coordinator for the Hawaiian Islands Humpback Whale National Marine Sanctuary.

“Once I realized how capable and powerful UAVs are, plus the ability to work with them off a small boat, I immediately thought about NOAA’s mission [to help entangled whales],” Pickett says.

According to Justin Viezbicke, California stranding network coordinator at NOAA Fisheries’ Marine Mammal Response Network, stressed whales become less tolerant of human presence with repeated boat encounters, not more tolerant. Drones are especially useful, then, since they can get close to the entangled animal without alerting it that a rescue team is approaching. “The idea is to minimize the reaction between the boat and the whale,” Pickett says.

Pickett and others are optimistic that drones could prove an essential tool for reducing the danger humans face in the course of a disentanglement operation. In July 2017, the Campobello Whale Rescue Team in New Brunswick, Canada responded to a call about an entangled North Atlantic right whale in the Bay of St. Lawrence. On board was Joe Howlett, a life-long fisherman and veteran whale first responder. After two passes, Howlett successfully cut the lines. But the whale, a juvenile male, unexpectedly flipped its tail, pinning Howlett against the bow of his boat and killing him.

Howlett’s death shook the response community. Volunteer networks in the U.S. and Canada went into shutdown mode, as government coordinators scrambled to retrain responders to better ensure their safety.

Viezbicke’s network obtained the first U.S. approval to respond to an entangled whale in the wake of Howlett’s death—a humpback weighed down by fishing lines, buoys and anchors near Crescent City, California. The rescuers were able to cut the lines free during what Viezbicke calls a “highly scrutinized but successful event.” While saving an individual whale is certainly worth cheering, Viezbicke says, “the program we’re running is just a Band-Aid for the larger problem.” Teams are only able to completely free entangled whales in about half of all attempts. Sometimes responders decide not to attempt a rescue for one reason or another; sometimes the whale frees itself.

Melissa Good, a regional entanglement response coordinator based in Dutch Harbor, Alaska, cites the case of an entangled humpback whale that died in a storm as typical. Good’s team brought the dead whale ashore to perform a necropsy and discovered two crab pots wrapped around the animal’s jaw. “The whale was emaciated and had a systemic infection,” Good says. “Both were the direct result of entanglement.”

Reports of entanglements have been increasing in some regions, including the West Coast, where humpback and gray whales are frequent victims. After averaging 10 or 12 a year, cases spiked starting in 2014, reaching an all-time high of 71 reported cases in 2016. On the East Coast, entanglement is the leading cause of death for the critically endangered North Atlantic right whale. According to NOAA, over 85 percent of right whales have entanglement scars, and a record 17 of them died in 2017.

The increase in entanglements could be explained, in part, by expanding populations of certain species such as humpback and gray whales, as well as increased awareness and reporting. But wherever whale foraging and human fishing overlap, the results can be disastrous. In April 2016, for example, 10 entanglements were reported off the coast of California within a few weeks of the opening of the Dungeness crab season.

“I’m really hopeful for freeFLY,” says Good, who is also seeing more entanglements in Unalaska Bay. “It’s going to be an essential tool for good documentation.” Such documentation, she believes, will push the conversation with fishermen and spur them to switch to practices that help prevent whales from becoming entangled in the first place. Solutions include rope-less fishing gear and lines designed to break away under pressure.

Two days after Andy Dietrick captured footage of the entangled humpback in Unalaska Bay, he went out in a response vessel with John Moran, a highly trained responder who flew in from Juneau. Dietrick piloted the drone while Moran’s team approached the whale in a Zodiac. Through the drone’s camera, Dietrick could see the shadow of the whale 20 to 30 seconds before it surfaced, which allowed him to coach Moran’s team into position. The hovering drone also helped Moran get a fix on the whale’s location. “The drone provides an amazing level of awareness for everyone,” Dietrick says.

Moran used a grappling hook to quickly cut the line binding the humpback’s head to its tail. But it took several hours and many more passes to cut the lines around the flukes. After making one final cut, Moran heard a popping sound, and the heavy gear that had been weighing down the whale suddenly floated to the surface. For a tense few moments, the whale was nowhere to be seen. Then the team heard it blowing in the near distance.

“Once that line was cut, it was dramatic. The whale really started moving,” says Dietrick, who followed the whale with his drone to make sure the animal was swimming normally.

During the two-day operation, Dietrick piloted 15 drone flights for a total of four-and-a-half hours of flying time. The experience proved the value of drones in all phases of the operation, he says.

Viezbicke and a Florida response network have also shown interest in freeFLY.

“It blows my mind that it’s taken us this long [to figure out how to incorporate drones into the response],” Viezbicke says. “It alleviates stress for the whale, and it protects us."

Imagery of whales taken by UAS platforms and those depicting rescue activities were conducted pursuant to and under the oversight of NOAA Fisheries’ Marine Mammal Health and Stranding Response Program (Permit # 18786-03) issued under the authority of the Marine Mammal Protection Act and the Endangered Species Act.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club