Getting Girls on Ice So They Can Change the World

What happens when glaciologists take teens to British Columbian mountains?

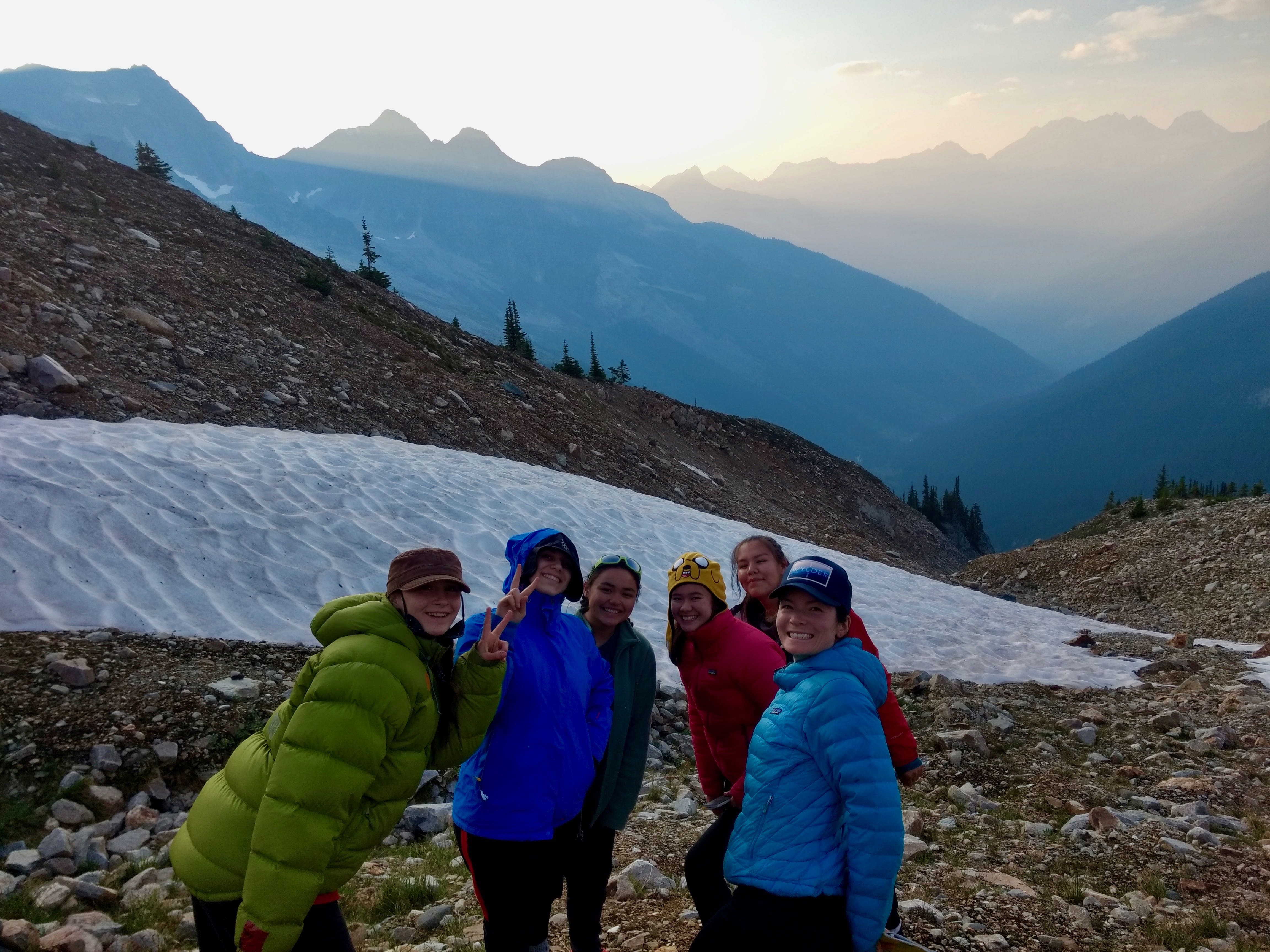

Photos courtesy of Girls on Ice Canada

From the moment she first saw glacial ice during a childhood vacation to Montana’s Glacier National Park, glaciologist Alison Criscitiello says she's been drawn to the harsh landscape and the stories the ice can tell us. “My parents said I became fanatical about glaciers. I was in awe.”

For Criscitiello, the frozen landscape was transformative. First came exploring the big mountains: In the Indian Himalayas, she led the first all-women’s summit of Pinnacle Peak. Then she ski-traversed Central Asia’s Pamir Mountains. As her interest in the role ice plays in global climate change developed, her studies took her to MIT, where she earned the school’s first PhD in glaciology.

Now an adjunct assistant professor at the University of Calgary, and Technical Director of the Canadian Ice Core Archive at University of Alberta, Criscitiello wants to give other young women access to the environment she’s always found so inspiring and empowering.

“Travel can be enriching,” says the woman actively laboring to give adolescent females access to no-barriers, tuition-free, science-based alpine expeditions. Criscitiello says she pointedly tries to find teen girls who might never otherwise have the opportunity to be mentored by strong women in such a raw and rugged environment. “We wanted to find the ones for whom the experience would be life-altering.”

Modeled on the Girls On Ice program that was launched in the U.S. in 1999, Girls On Ice Canada takes 10 young women ages 16 or 17 on annual expeditions to high mountain landscapes. August 2018’s pilot expedition to the Illecillewaet and Asulkan glaciers of British Columbia included teens from across Canada, from a diverse range of backgrounds. Expeditioners, for instance, included Haylee Yellowbird, from Alberta’s Paul Band Reserve, and Syrian newcomer Yumna Sakkar, whose family settled in St. John’s Newfoundland.

The Canadian GOI leadership team includes Criscitiello; Jocelyn Hirose, a resource conservation scientist with Parks Canada; Eleanor Bash, a PhD student in glaciology at the University of Calgary; and Cecelia Mortenson, an internationally certified mountain guide. Criscitiello says the women were all motivated to develop the program in part because of the sheer number of Canadian girls who had applied to the U.S. GOI. “We wanted a program in our own home mountains.”

While any mountain could provide education and inspiration, the site selected in British Columbia’s Glacier National Park is particularly fitting. Established in 1886, the park has long been important in glacial research circles. This is thanks largely to ground-breaking glacial photography by the Vaux family, and particularly Mary Vaux, the painter and photographer who in the 1880s became the first woman to ascend all 10,000 feet of British Columbia’s Mount Stephen. The Vaux family first visited the park’s Illecillewaet glacier in 1887, and on a return trip, noticed the glacier had retreated. Their annual photos of the retreating glacier were instrumental in the development of the field of glaciology, and Mary continued to visit and photograph the glacier every summer until her death in 1940.

Following in Vaux’s pioneering footsteps took a lot of support. GIO Canada spent three years planning and raising funds for the expedition, and collecting donated gear and supplies. The journey ultimately came together thanks in large part to financial support from the W. Garfield Weston Foundation.

To kick the trip off, the girls headed to Yoho National Park, where they got used to using the donated gear and were trained in the observational skills needed for immersion science. From there, they hiked into the mountains and made a base out of the Alpine Club of Canada’s Asulkan Cabin. There, they developed technical snow and ice skills and began formulating their own science experiments.

Some of the girls, including Sakkar, had never seen or been on a glacier. Most knew next to nothing about high alpine ecosystems when they began their journey. But thanks to the support of the guides, artists, and scientists, the girls became proficient in their new environment, and each of them successfully climbed all 9,215 feet of mini-Young’s peak.

When they weren’t hiking, the teens learned more about glacial ecosystems, created glacier-inspired art, and designed their own experiments on topics that piqued their interest—such as where crevasses form on the Illecillewaet glacier, what the mass balance of the glacier is, and how certain animals may have been habituated near their cabin.

Following their trip, the teens had a chance to reflect on their journey and present the results of their scientific inquiry at the University of Calgary's Biogeoscience Institute in Kananaskis Country.

“Everything in my life, from being a mountain guide to becoming a glaciologist, led to this,” Criscitiello says of GOI. She adds that expeditions like this don’t change just the girls, but also those around them. “There’s a ripple effect. Each girl learns she has the power and passion to change her community.”

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club