Great White Sharks Are Back in Southern California—Now What?

When a conservation success story gets complicated

Photo courtesy of CSU Long Beach Shark Lab

Triathlete Maria Korcsmaros was swimming off the coast of an Orange County beach in May last year when a nine-foot great white shark tore into her right arm. Great whites approach prey from below, so Korcsmaros didn’t see it coming. She felt a crushing pressure and teeth breaking through her skin, and immediately knew she was in trouble. Luckily, the shark didn’t circle back, and a lifeguard boat that happened to be 100 yards away pulled her out of the water. It was the first attack on record in the city of Newport Beach, a popular tourist destination. “We had seen more sharks than usual for a few years in Orange County,” explained Rob Williams, chief lifeguard for Newport Beach, “but that’s when we realized, ‘OK, now it’s real.’”

Sharks come with the territory along certain stretches of coastline. The sand-bottom breakers along Florida’s Atlantic coast, the cold cliff’s-edge waters of Northern California, Hawaii’s reefs and beaches—these are typically considered the shark capitals of the United States. According to one shark attack data aggregator, Florida experienced an average of seven attacks per year between 1950 and 2000, while Hawaii and Northern California both averaged between one and two per year. Ultimately, this was a low risk compared to other hazards (like driving to the beach), but it was enough to instill fear among oceangoers. Southern California averaged only about 0.5 attacks per year in that same period. Surfers have a word—"sharky"—to designate waters in which they divine a certain fishy presence, and the beaches south of Point Conception are rarely described as such.

But that may be changing. Great whites are showing up in droves along the Southern California coast. Chris Lowe, director of California State University Long Beach’s Shark Lab, noticed the first signs of population growth about 20 years ago. “We were telling the public that shark populations everywhere are declining because they’ve been overfished, but some of the data we were getting was suggesting that the white shark population was going up. And I couldn’t believe it,” he said.

That population growth became more evident to the public last summer, when Leanne Ericsson suffered a near-fatal attack at a popular surf spot 20 miles south of where Korcsmaros was bitten the year before. Ericsson’s would prove to be the only confirmed attack that summer, but a string of sightings and close calls followed. Two weeks later, the Orange County sheriff's department spotted a group of sharks close to the surfline. “Be advised, State Parks is asking us to make an announcement to let you know that you are paddleboarding next to approximately 15 great white sharks. They are advising that you exit the water in a . . . uh . . . calm manner,” they announced from a helicopter to surfers below. That day alone, 27 individual sharks were spotted in Los Angeles and Orange Counties, and footage from the sightings made local and national news.

Great whites gathered off Capistrano Beach in April 2017 | Courtesy of @mattlarmand

Great whites gathered off Capistrano Beach in April 2017 | Courtesy of @mattlarmand

Sightings continued through the summer. While some news reports bordered on sensationalist, most were even-keeled, noting that most of the visitors were juvenile great whites, which pose little threat to humans. While it’s hard to collect precise information on shark activity, Chris Lowe called it the “sharkiest summer that we’ve seen,” in an interview with Surfline.

The shark activity was cause for celebration for scientists like Lowe who view sharkier shorelines as a bellwether of natural population rebound. Overfishing and trophy hunting depleted shark stocks worldwide over the last century, and the great white population off of California was no exception to this trend. For years, commercial fisheries in California occasionally landed juvenile great whites, and their meat—usually labeled simply as “shark”—could be found in fish markets in the state as recently as the 1990s. In 1994, California protected great whites from fishing, bycatch, and trophy hunting under its Endangered Species Act, and marine mammals—a favorite food source of the Pacific great whites—have been safeguarded since the United States Marine Mammal Protection Act of 1972. “When you look at how much great white populations have grown in coastal communities like Southern California, it looks like ecosystem recovery,” says Lowe.

Usually this sort of recovery prompts relief and celebration—but Lowe understands that sharks are a unique case. “This can go two ways,” he explains. “I can say, ‘It’s awesome. Shark populations are coming back!’ But it only takes one person to be bitten and it becomes this unrealistic fear that starts to overwhelm people.” Southern Californians are now faced with a difficult question: What to do when a conservation success story inspires more terror than celebration?

Chris Lowe releases a juvenile great white | Courtesy of CSULB Shark Lab

Chris Lowe releases a juvenile great white | Courtesy of CSULB Shark Lab

To be fair, that fear has been stoked by more than just one bite. Thirty-nine attacks between Santa Barbara and San Diego have been recorded since Lowe first began studying sharks in Southern California in 1997. There were only 10 attacks in the previous 20-year period. Lowe’s point is that the fear has grown out of step with the actual threat. Great whites almost never seek out humans as prey. Southern California oceangoers are far more likely to drown than suffer a shark bite—in 2014, nine people died in ocean drownings in Orange County alone. Still, even experienced surfers worry. “I’m afraid, and I’m afraid for my children,” admits Ian Cairns, an Australian surfer who now lives in Orange County.

Cairns has seen this before, and he believes we can learn from past mistakes. Now 65, he became famous in the 1970s for his fearless mastery of powerful waves. During his early days as a surfer in Western Australia, he paid little mind to what might be lurking beneath the surface. “Growing up, I never saw a shark, and there had been no attacks,” he recalls.

Today, the cold-water waves he frequented as a kid inspire fear among surfers worldwide. Australia is currently in the midst of a shark-attack epidemic that has reached the tenor of a national security crisis. Last year there were 15 attacks and two deaths in the states of Western Australia and New South Wales alone. An economic fallout has hit a number of regions as tourists avoid areas where attacks have occurred. “It’s really bad,” Cairns says. “People are afraid to go surfing, and economically, towns are collapsing.” In 2014, after a string of five shark-related deaths in 10 months, the Western Australian state government implemented a “Shark Hazard Mitigation Program.” Floating barrels strung with huge baited hooks (known as “drum lines”) were placed near popular beaches throughout the state. Sharks large enough to pose a threat to humans would be “humanely destroyed”—killed with a shot to the head.

Of the 172 sharks hooked during the program’s seven-month trial run, 50 measured over nine feet and were destroyed. Fourteen more died on the drum lines, and four were shot after being determined to be too weak to survive. All 50 large sharks were tiger sharks, which haven’t been responsible for an attack in Western Australia in years. Not a single great white was caught. Animal welfare and environmental activists lobbied relentlessly against the program. Due in part to the activists' hard work, the program was downsized after the botched trial run and eventually discontinued in 2017.

It’s hard to imagine a catch-and-kill solution being implemented in the United States but it’s not out of the realm of possibility. This year, a county commissioner in Cape Cod proposed setting up drum lines after a shark attacked a seal near a crowded beach, erroneously claiming that Australia had found success with a similar policy.

Chris Lowe stresses that the problem isn’t going to fix itself. “I can’t see populations going down,” he says. Relatively little is known about great white migratory patterns, but scientists believe that adults often return to the feeding areas they frequented as juveniles. Younger sharks rarely attack humans, but those teenage great whites that made national news this summer could pose a serious threat after a few years of beefing up on seals and manta rays during their migratory jaunts.

Lowe is clear, however, that predictions are complicated by one major unknown variable: climate change. Warming oceans could be affecting shark behavior in ways scientists don’t yet understand, he says. Juvenile sharks are attracted to warm waters, “It could be that white sharks are enjoying the benefits of the current climate state right now, but in 20 years they may not. Or that as waters warm they start occurring in places that they’ve never occurred before. These are things we just don’t understand.”

Lifeguard chief Rob Williams made it clear his team is focused primarily on the here and now when it comes to sharks. “We have a new threat that has already started to show itself,” he says. “The question we’re asking ourselves now is how are we going to address it?”

Technology may be able to provide a solution. Traditionally, lifeguards have relied on sighting reports and boat reconnaissance to spot sharks in their waters, while swimmers', surfers', and divers’ only means of attack prevention would be a judgement call to stay on land that day. Over the past few years, high-tech shark-detection systems and consumer products that claim to prevent attacks have become available. New South Wales is deploying megaphone and life-raft-equipped Little Ripper drones that spot sharks using AI software at some beaches. Surfers can wear an electromagnetic bracelet called Sharkbanz that deters sharks. Divers and swimmers can don blue wetsuits with a camouflage pattern designed to make them invisible to the predator. Most of these products have been developed by Australian companies, some in partnership with state and federal governments. The fear surrounding attacks has created a lucrative market.

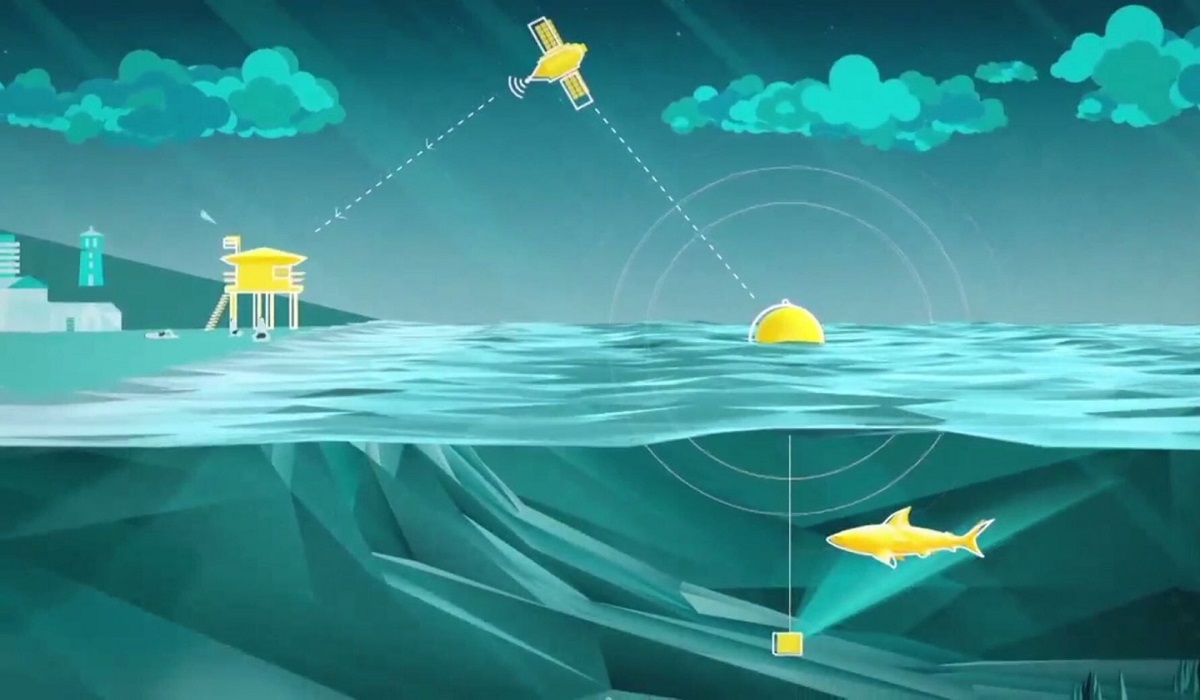

Ian Cairns partnered with one of these shark-tech companies a few years ago—Shark Mitigation Systems (SMS)—which is now making headway in the United States. The city of Newport Beach announced in September that a half-mile stretch of its shoreline will be outfitted with a system of shark-detecting buoys developed by the company. The Clever Buoy system uses sonar to detect shark activity and provide lifeguards with an immediate update whenever a shark swims close to shore. The city chose Corona Del Mar State Beach for its trial run—the same beach where Maria Korcsmaros was attacked last year.

“The lifeguards are on the front lines. The more tools they have, the better,” says Lowe about Clever Buoy. Lowe’s Shark Lab has worked on tagging sharks and setting up tracking buoys along the Southern California coastline, but that data is only downloaded once a week. The Clever Buoy system promises to provide the size, location, and potentially even species of any shark that swims within its range—all in real time. Its sonar detects any animal that swims close to shore, not just sharks that have been tagged in advance. Following a detection, Williams says, lifeguards would make a decision whether to locate it with a helicopter or a boat, and whether to close the beach or simply post warning notices.

Clever Buoy diagram | Courtesy of Shark Mitigation Systems

Clever Buoy diagram | Courtesy of Shark Mitigation Systems

Clever Buoys have never been used in U.S. waters before, but they have been tested in Australia at a number of beaches, and were deployed during a World Surf League competition at Cairns’s home break in Western Australia this year. Their sonar technology operates in a frequency range SMS says has no impact on sea life and has been determined to be noninvasive by the Australian EPA.

The trial program won’t begin until next summer at the earliest. The Clever Buoy system still needs to be approved by various U.S. state and federal regulatory groups before the trial program can begin. And there’s the issue of the price tag—$1 million for a half-mile stretch of beach.

“There’s probably no one device or tool that’s gonna keep people safe at the end of the day,” Lowe says. Each attack-prevention product comes with a certain downside. Some, like Clever Buoy and Little Ripper drones, are too expensive to become a widespread solution. Others may not provide the protection they promise; Floridian Zack Davis was bitten by a blacktip shark while wearing a Sharkbanz he had received for Christmas days earlier.

“It really comes down to people’s knowledge and ability to evaluate risk,” Lowe says. He says surfers may have to make sacrifices to stay safe, like staying away from areas where sightings have been recently reported and avoiding surfing alone. His ultimate goal is to change the public’s perception of the animal he has spent decades studying. “I used to think just doing good science would be enough, but I have to do more. Getting the science out to the public as education is gonna be essential.” If the fear is here to stay, he hopes to spread the message that our most-feared predator is worth protecting.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club