Deep River Blues

A grieving Mississippi visitor takes to the water, guided by youths

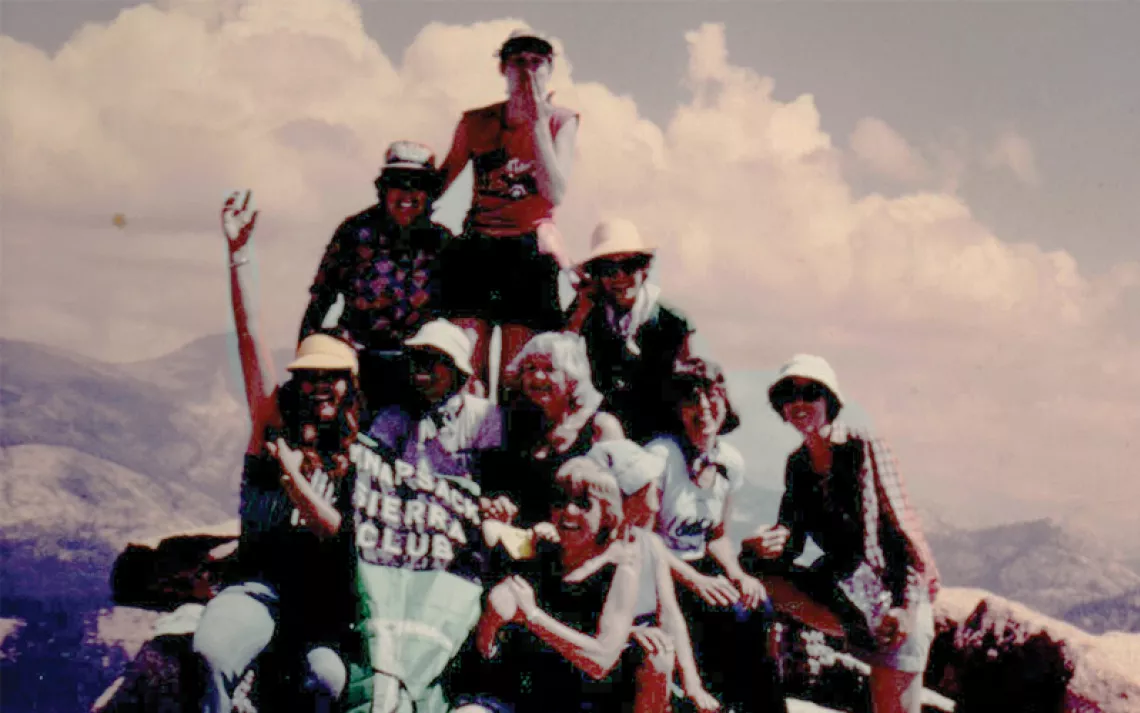

Images courtesy of Chris Battaglia

Dingo’s River and Blues, 2008

During my first trip to Clarksdale, Mississippi, billed as the home of the Delta Blues, I stayed in John Lee Hooker’s favorite room at the Riverside Hotel. Ike Turner once lived there, and it’s where Bessie Smith took her last breath.

I strolled down the street to the banks of the Sunflower River, site of Clarksdale’s annual River Blues and Gospel Festival. At its edge, I found a graveyard and a run-down building. Slow blues riffs crept through a sliver of open door. A woman poked her head out, then invited me inside.

“Red? Dingo? Can we get this lady a drink?” The sign on the wall said “Red’s.” The helpful lady was Robin. Though the ceiling seemed about to cave, the walls were draped in memorabilia from blues pilgrims and artists around the world. This was Red’s Juke Joint.

Red himself, an icon among international blues fans, nodded gruffly, while Dingo—DJ, bluesman, and Red’s right hand—gave me a warm smile.

“Where you from, Baby?” asked Dingo.

“Where you from, Baby?” asked Dingo.

“Colorado,” I said, smiling back.

Small talk grew bigger over a tall can of Budweiser, and I asked Dingo about his name.“I bought a pair of Kangaroo cowboy boots, and the word ‘Dingo’ was on the heel,” he explained. “Then I met a bunch of Australians here at Red’s, and Red say, ‘Oh, that’s an Australian dog right there. He Dr. Dingo.’”

Then in his early 50s, Dingo had been driving trucks since 18. He was about to retire. “More time for fishing on the Sunflower.” For Dingo, the blues and the river went hand-in-hand.

“When you’re listening to the blues, it like going to church. Sit back, get comfortable, relax your mind. Like catchin’ catfish on the Sunflower,” he said. “Makes you feel real good.”

Since that day, I’ve returned to Clarksdale most every year to work the Juke Joint Festival. I always visit Robin, founder of Clarksdale’s historic cultural center, the New Roxy, and her wife, Lena, who works at the local Quapaw Canoe Company. Named after a Native American term for “Downstream People,” Quapaw is a paddling adventure outfit that trains Mississippi Delta youths—many of whom would never otherwise get out on the water—to guide groups in voyageur-style canoes.

Dingo eventually became a shuttle driver for Quapaw and started spending more and more time fishing the Sunflower and the Mighty Mississippi. Our heartfelt conversations about nothing in particular resumed a couple times a year, whenever I came to town. Sometimes, Dingo called to tell me it was time to visit.

Our friendship lasted nearly a decade, until 2016, when he passed away.

2017: The River Flows On

“I think being on the Sunflower is more of an emotional activity for me. It just makes me feel good about everything around me.”

“I think being on the Sunflower is more of an emotional activity for me. It just makes me feel good about everything around me.”

Valencia, age 19, wears a big smile. An alumna of Quapaw’s Mighty Quapaw Apprenticeship Program, a hands-on, multiyear youth development program focused on teamwork and outdoor adventure challenges on the Lower Mississippi River, Valencia now instructs her peers in the river arts.

“When I first started canoeing, I was always jumpy,” she says. “I’d never been out in nature, and I wasn't used to all the bugs, fish, and animals. Over time, I learned that nature is more scared of us than we are of it. “

Like Dingo, Valencia is a Clarksdale native. Whereas Dingo turned to fishing to watch the river unfold, Valencia loves being on the water. A first-generation river enthusiast and more of an R&B fan, she admits, Valencia has become an ambassador for her community. “My goal with teaching river arts is to teach people that water isn't our enemy, and nature doesn't hate us.”

We walk through the Quapaw facility, where a colorful, hand-painted poster states, The Mississippi Connects Us All. On the shelves, accomplished rivergoer and Quapaw proprietor John Ruskey’s newly released Rivergator: Paddler’s Guide to the Middle/Lower Mississippi details river-navigating logistics from St. Louis to the Gulf of Mexico.

Out back, the Quapaw shuttle’s exterior boasts brightly painted river creatures. The words Warning: We Brake for Turtles caution potential tailgaters.

Out back, the Quapaw shuttle’s exterior boasts brightly painted river creatures. The words Warning: We Brake for Turtles caution potential tailgaters.

“Dingo was the only one who could back that up,” says Lena, with a chuckle. “Dingo used to chase the snakes out of the river. It always made the kids squeal. Dingo wasn’t afraid of snakes!”

She hands me an adze, a tool used to chip off the rough layers of wood from the canoes before smoothing, sanding, and seating. I hack a few chips, sampling the work the kids master through the canoe-building component of Quapaw’s programming.

During the last few years, Dingo started carving river sticks into canes, with blues lyrics and drawings etched into the wood. A Dingo stick was a thing of beauty, and I would see them around town—at Red’s, or the New Roxy. They were another way Dingo shared his river and his blues.

“I always talked to Dr. Dingo,” Valencia says. “He was the sweetest man. And he made the dopest canes.”

On the Water

After all these years consuming the blues and the Budweiser at Red’s, today is my first time out on the Sunflower.

I’m here to join the Mighty Quapaws, as the young leaders are called, and Mark River—river guide, youth leader, and Southern head of 1 Mississippi, an organization of “river citizens” who advocate for river protections at local, state, and national levels.

My paddling partner, Robyn, age 17, eases into the stern of our canoe. “I like the outdoors, to relax and chill.” In muddy river boots and jean shorts, Robyn does appear chill. “But canoeing is hard sometimes,” she says, wiping her brow. Her costume-variety pearl stud earrings flash in the hot May sun.

“You’re a good leader,” I tell her from the bow. “You’re strong!”

“Some people have more muscle though, and I got to keep up, or they look back like, ‘Let’s go.’ But when I look up and see you smiling at me and stuff,” she says, “I feel good to row.”

“Some people have more muscle though, and I got to keep up, or they look back like, ‘Let’s go.’ But when I look up and see you smiling at me and stuff,” she says, “I feel good to row.”

“Dingo used to chase snakes from the river.” I hear Lena’s voice, echoing, as we paddle through still waters and low-hanging cypress branches.

Sure enough, as we round a lazy bend, there’s a giant plop. I gasp. The kids shriek, then giggle.

Mark laughs. “It’s a carp,” he says. “That particular one always makes a big splash.”

Ol’ Man River

Before leaving town, I stop into Red’s.

Ellis, or Big E, is working the door. Ellis lives a few miles up the Sunflower, and since Dingo’s departure, he’s started driving the Quapaw shuttle.

“What’s the Mississippi like?” I ask.

“It somethin’.”

“Something like what?”

Ellis widens his eyes.

I tell him I was a friend of Dingo’s.

“Awww come here, Baby Girl.” He pulls me in for a hug.

“Dingo was my best friend,” Ellis says. “We used to sit on that porch, in those rockers, and work our sticks.”

I conjure the scene and smile.

“Now that he’s gone, I don’t sit in those rockers no more. Just ain’t as much fun.”

He pauses.

“Sometime those rockers move. I think it’s Dingo.” Ellis chuckles, and his smile fades. “It probably just the wind.”

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club