Dispatches From a Youth Delegate at COP22

An American activist reports from Marrakesh on election fallout, die-ins, and climate justice

Photo by David Tong

In September 2016, a group of youth climate activists and elders gathered around a campfire at Canticle Farm, an urban permaculture center in Oakland, California. The flames cast shadows on the faces of 13 youth delegates, including myself, headed to Marrakesh, Morocco, for the 22nd United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP22)—an annual gathering to assess international progress in mitigating climate change. The group came from Utah, Hawaii, Navajo Nation, and beyond. SustainUS brought us together as part of a Storytelling Challenge.

SustainUS—a U.S. youth-led organization committed to climate justice storytelling, sustainable development, and progressive campaigning—trains and organizes youth delegations to attend UN conferences. In Oakland, the SustainUS COP22 delegates got to know one another while practicing the basics of nonviolent communication, exchanging stories of our individual work in the climate movement, and sharing meals beneath fig trees. In the past, SustainUS has primarily functioned as a policy-oriented organization; the transition to storytelling happened in the wake of COP21. Morgan Curtis, this year’s delegation leader and a recent recipient of the Spiritual Ecology Fellowship, chose to lead the COP22 SustainUS delegation with a focus on spirituality, sustainability, and group harmony.

Zo Tobi—a musician, climate justice activist, and one of the elders at our fire circle that night in Oakland—listened as SustainUS veterans told stories about COP21 in Paris and the utter exhaustion of tracking the negotiations. “No one ate or saw daylight,” a returner said. Tobi pulled his beanie further down over his ears and put his hands on his knees, leaning toward the flame. “What would it look like to leave COP22 more energized than when you arrived?”

Later, as I traveled to the conference, I held Tobi’s words close. This COP, as I understood it, would not produce any glossy solutions. The climate crisis can’t be halted with the push of a button.

COP22, the so-called COP of action, was intended to address the practical means of implementing the landmark climate action plan hatched at COP21. The first-ever universal, legally binding climate change deal, the Paris Agreement aims to limit global warming well below 2 degrees Celsius and to reduce global greenhouse gas emissions before 2050. I brought along my audio recorder to COP22, seeking narratives from civil society members doing great work within the movement. My aim was to amplify those stories of climate change that might not otherwise be told

In college, I studied folklore and mythology and, during a 2013 solo bike trip down the Mississippi River, found a passion for collecting stories relating to water and climate change. Since the September 2014 People’s Climate March, I’ve been traveling, mostly by bicycle, on a mission to collect 1,001 stories about water and climate change. I was fortunate to launch my travels with a grant from my alma mater, Harvard, for a year of solo “purposeful wandering” after graduation. At COP22, I wanted to learn what might be possible working together in a group.

On November 7, the first day of the conference, it was raining. A group of us left our riad early and headed to the city center, where we boarded buses emblazoned with the circular COP logo. Twenty minutes later, we stepped onto a patch of earth that, weeks before, had been a rocky, barren landscape on the southern outskirts of Marrakesh.

I looked out over a row of white, pointy tents, obscured behind a canvas printed to look like the red walls of the medina. Armed guards fortified the entrance. From a distance, COP has the aura of a circus, minus popcorn and fire-eaters, and plus a few firearms.

Flags from 197 countries rippled in the drizzly breeze. Men in army fatigues, expressionless, marched in straight lines around the rectangle of earth that held the flags; no one was allowed to touch the flagpoles, or even come close. Were they worried, I wondered, that someone would steal them?

Our shoes trailed red dirt inside the conference. Entering COP involves passing through airport-esque security. I soon mastered the routine: Pull out laptop, phone, and audio equipment. Put in plastic bin. Take sip of water to ensure that it’s not a weapon. Succumb to my hair being patted down. Smile at the woman with the metal detector wand as she scans my arms and legs. Apologize for leaving change in my pocket. Repack my belongings. Rinse and repeat.

COP22 was divided into two zones: the Blue Zone and the Green Zone. Badges and security clearance were required to enter both, but the Green Zone was open to the public. More of an exclusive club, the Blue Zone was the site of the plenary (the main meeting space) as well as several smaller meeting rooms, a handful of overpriced coffee booths, and an always-buzzing media tent, where I witnessed Amy Goodman recording a few episodes of Democracy Now! Also located in the Blue Zone were rooms named after oceans and seas, where civil society groups held meetings—“Meet outside Arabian at noon!” was a common refrain. When meetings weren’t in session, government delegates (a.k.a. “party members”), civil society members (“observers”), and members of the international media would collapse on the floors of these rooms for brief naps or huddle around their power outlets, typing frantically on phones and laptops.

The Green Zone was COP22’s civil society space, where non-state actors—municipalities, businesses, and NGOs—gathered to showcase their climate change work. To me, the Green Zone sounded like a cacophonous sales meeting. Nuclear companies and Moroccan mining organizations staffed booths alongside solar energy stalls and grassroots groups such as Pikala, a nonprofit that aims to reinvigorate bicycle culture in Marrakesh by providing free tune-up clinics and transporting otherwise scrap bikes from the Netherlands to Morocco.

On the first day, I wandered aimlessly within the Blue Zone, not knowing where to go. The meeting rooms were mostly off limits to observers like me, but a few of us snuck inside the plenary on lunch break. Near the back of the room, fellow SustainUS delegates and I found the United States chair toward the back of the room—seating is organized alphabetically—and took a seat at the table, gesturing as we joked about what U.S. participation in the climate negotiations might look like if youths were given decision-making power. Why should old white men decide the fate of generations who will be growing old after all the decision-makers are long gone?

Before long, we sank into despair imagining what the negotiations would look like if Trump were president (said despair only mounted in the wake of the next day’s election results). Dejected, I browsed my Twitter feed and found a video of an ice skater in a T. rex costume. I showed it to the others, and then leaned over to a government representative from the UK, our neighbor in the “U” section, a middle-aged white man, back early from lunch. “Do you want to watch a video of a T. rex ice skating?” I asked. “Why not?” he said. Moments later, we were all laughing.

This was the most interaction that I had with a negotiator for the entirety of the conference. As an observer, my role in the negotiations was severely limited. I didn’t set foot inside the plenary again; each of the civil society members present were only given two chairs, and it felt important to us SustainUS delegates that those chairs were occupied by indigenous people and people of color. Sometimes, the best way to be an ally is to step back and listen.

Following that first day of COP, I walked home, fortifying my mental map of the city. The air was red and dusty. A motorcycle rounded the corner and almost knocked me over.

Over the course of our two weeks at COP22, SustainUS organized three main actions: 1) a U.S. election response, 2) a prayer for Standing Rock, and 3) a die-in inside the Green Zone booths of two Moroccan corporate polluters.

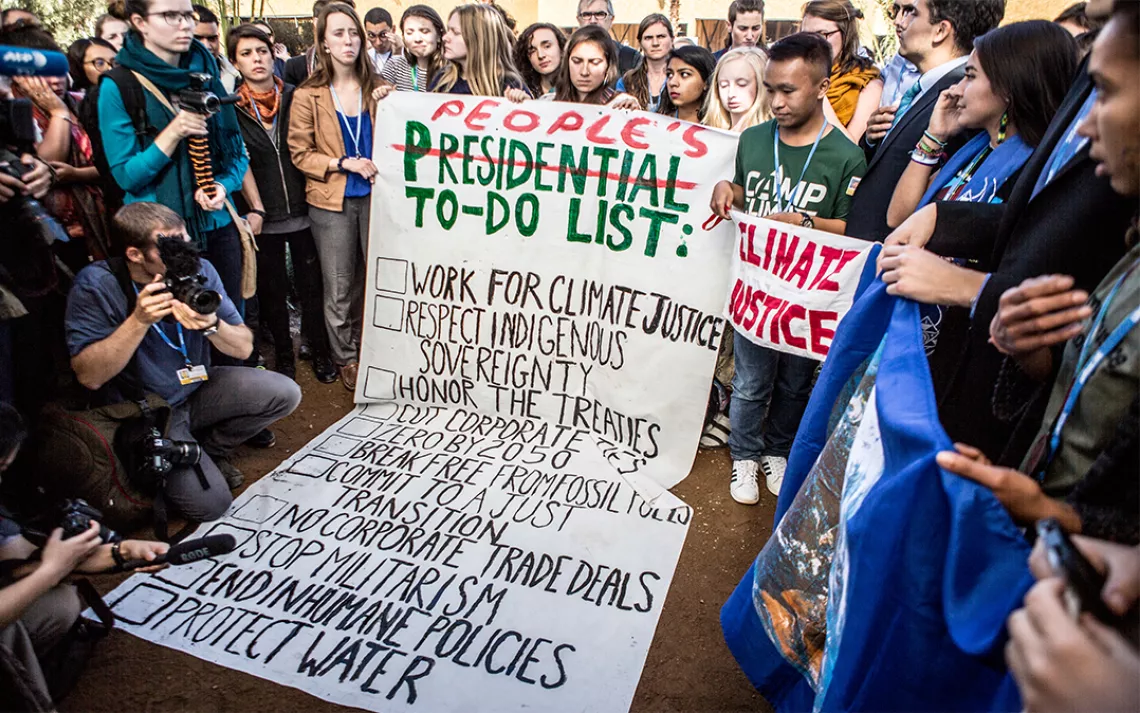

Our election response action was cathartic, to say the least. The night of the U.S. election, SustainUS created a banner that read “Presidential People’s To-Do List” that included “Work for climate justice. Respect indigenous sovereignty. Zero [carbon] by 2050,” and “Break free from fossil fuels.” The decision to cross out the word “presidential” came in the early hours of the morning, when it became clear that Donald Trump would win—a result that reinforced to us that it’s the American people, not the government, who are going to have to respond to the climate crisis.

The next day, SustainUS created space, both inside the Blue Zone and outside in front of the UN flags, for youths to be fully present in their rage and sadness. My grief was reflected back at me; I wasn’t the only one crying as we sang. People showed up from Switzerland and New Zealand and Canada and Brazil to share stories of their resolve to continue fighting against climate change. I left with the confidence that I am not alone in this fight.

Days later, some 200 people attended an indigenous-led prayer ceremony we organized for the water protectors at Standing Rock. Within view of the UN flags, we smudged with sage and circled up, with the intention of holding space for prayer without media—the “without media” piece being no easy feat. A few among us broke the circle to run around asking those who held up smartphone cameras to please stop and instead join us. One of the flag guards was especially obstinate. “This is my job,” he told me, a hint of malice in his voice.

“If I walked into your mosque and started taking photos, and you asked me to stop, I would stop,” I said. After that, he put his phone away and watched us from a distance, leering. Hello, military state, I thought to myself.

Photo by Remy Franklin Our final action, a two-part die-in in the Green Zone, was performed with the intention of shedding light on other pressing environmental justice issues we had learned about that impact Moroccan communities suffering at the hands of corporate polluters—companies that also happened to act as COP22 sponsors. For this, we targeted the booths of Managem, a mining company, and the Office Cherifien des Phosphates (OCP Group). Managem operates Africa’s largest silver mine in Imider, a town 300 kilometers south of COP22. Silver mining is a water-intensive process, and Managem usurps water from Imider’s indigenous Amazigh community. The Amazigh of Imider depend on subsistence agriculture and are already suffering the effects of climate change through desertification. OCP, a phosphate company based in Safi—a coastal town 150 km northwest of COP22—has devastated local fisheries and introduced toxic waste that kills nine or 10 people per year. The thousands of gallons of toxic waste they pump out per minute have created a brown sludge streak along the coast.

We learned of these local environmental justice struggles through Nadir Bouhmouch, a Moroccan photographer and activist who had been interviewed before COP on Democracy Now! Prior to the conference, one of the SustainUS delegation members started talking to Boumouch on Twitter about environmental justice issues in Morocco, and when we arrived, he made it possible for several among us to travel to Safi to witness the pollution firsthand, and for a delegate member from Navajo Nation to visit Imider.

In solidarity with Moroccans who die at the hands of these companies (and in protest of the fact that both were COP22 sponsors), 20 youth activists marched into Green Zone booths and counted to three. We then dropped to the floor, dead. Two among us remained standing to unfurl banners containing our message: “The World Stands With Imider and Safi.” After a few minutes, we stood up and burst into a chant: “Protect our water, not corporate greed! Protect our water, not corporate greed!” I pounded emphatically on the walls of the Managem booth to punctuate our words. The employees huddled into the periphery and cast their eyes downward. Some 50 people looked on, photographing and video-recording our chants. My heart was beating fast for hours afterward.

These demonstrations aside, I left COP22 disillusioned with what I’d witnessed within the UN tents: everyone in suits rushing by one another, not making time to stop and talk, or to even look into the eyes of those who had traveled to the negotiations specifically because they have so much at stake in this struggle. I left asking myself why heads of state aren’t taking directives from youths or indigenous peoples. Why hadn’t indigenous sovereignty—a key issue at the center of the #NoDAPL struggle—been put on the table? I wanted to know why the indigenous leaders I met had been shunted to the position of “observers” rather than negotiating party members. Despite this sadness, I was empowered by the sheer force of climate activists gathered in one place. I couldn’t possibly listen to everyone’s stories in Marrakesh, but I wanted to.

I view storytelling as a way of posing questions that are at the core of our identities. Where are we going, and where do we want to go from here? Storytelling can be a form of protest, as was my experience of sitting down at COP22 with an indigenous leader from the Ecuadorian Amazon to hear directly about how oil companies have desecrated her sacred lands. Listening, like marching in the streets, can function as a form of activism. Combatting climate change, I believe, requires us to listen to one another—something that the COP negotiations attempt to achieve but might not always make possible. How do we engage people who are far away from these white tents, who don’t have the privilege of being gathered in this space? How do we engage with those who don’t know what COP is?

I don’t have those answers, but COP22 left me all the more convinced that in the face of the climate crisis, storytelling is one of the most powerful tools we have. Our power comes from nonviolent direct action in tandem with climate justice storytelling. We must not only act, but also loudly tell the stories of why we have done so. In telling stories, we will into existence the more-just world in which we aspire to live.

On the final day, I exited COP22 arm in arm with fellow youth delegates from SustainUS. We sang as we reentered the world.

We have got the power. We have got the power.

We have got the power. It’s in the hearts of us all.

We left assured that it is everyday people, not only heads of state, who will lead the kind of innovative solution-making that the climate crisis requires.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club