Hope in the Midst of Ecological Dystopia

Cli-fi books for the young-adult reader

Climate change is infamously hard to wrap our heads around, and perhaps even harder to attach our hearts to. The remodeling of the entire planet is downright scary, and the demands that climate change places on us—the demands of individual attention and collective action—can be disorienting. While climate change discussions are often driven by political activists and scientists, the scale and scope of the changes we are making to Earth may make it a topic perhaps best suited for the philosophers and the poets.

To best prepare for the times to come, some argue, we will need to visualize a world of climate chaos and to walk through different imagined futures—narratives of action and inaction, of hope and despair. What better way, then, to introduce youths to the possibilities that stretch before us than YA climate fiction?

Climate fiction, or cli-fi, first made a splash with Margaret Atwood’s MaddAddam trilogy. It began to be recognized as its own genre around the time of Kim Stanley Robinson’s Science in the Capital trilogy, and established itself firmly in mainstream literature with Barbara Kingsolver’s 2012 novel Flight Behavior. Since then, young-adult cli-fi titles have exploded onto the literary scene. They are a great way to reach the readers whose lives will likely be dominated by the impacts of climate change—and, perhaps, spur them to action.

Here are some of my favorite YA cli-fi books, organized by age, since some titles are not appropriate for younger imaginations.

Ages 11 to 14

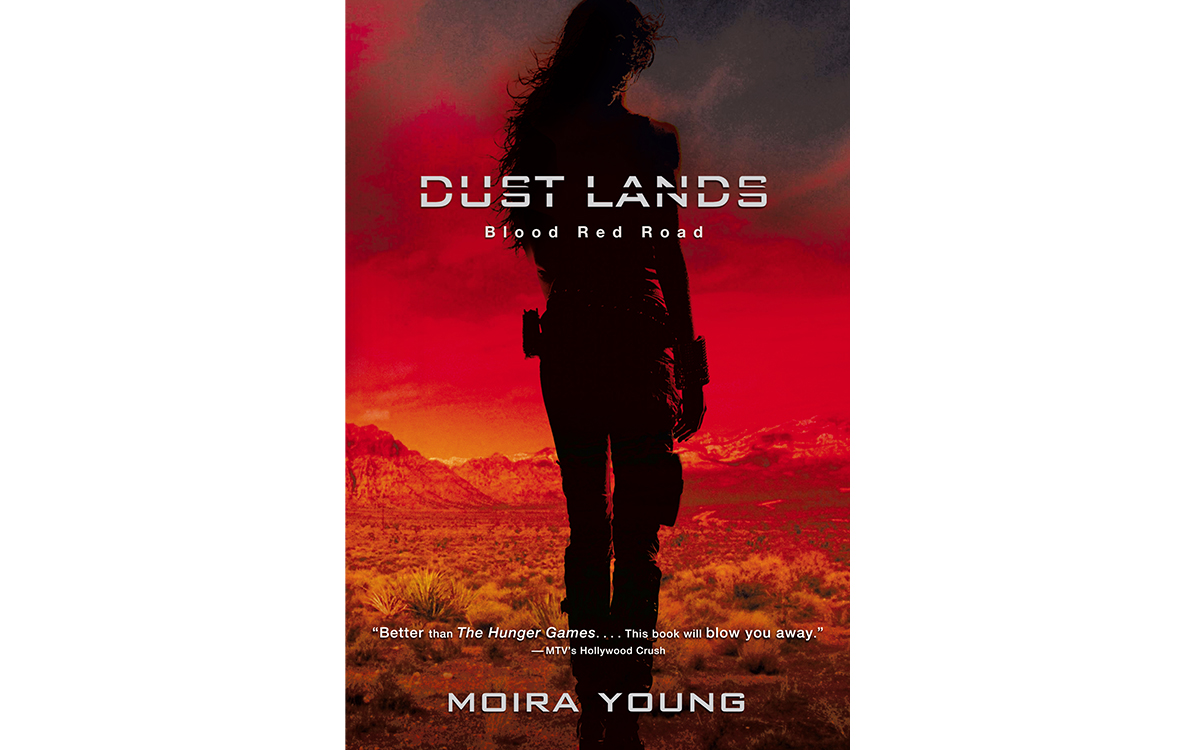

Blood Red Road by Moira Young (Margaret K. McElderry Books, 2012)

Part one of the Dust Lands trilogy, Blood Red Road, is the gritty story of Saba, a fierce young fighter who has set out on an epic journey to find her kidnapped brother, Lugh. Saba has to navigate through a wasted world swirling with dust storms, full of landfills, and baked by heat—but she has the help of a few friends. There’s the roguelike Jack; her sister Emmi, whom Saba dislikes; and the Free Hawks, a group of female warriors who love to hate on the governing authorities.

What happens to the travelers and how the journey ends (or does it?) is best left for readers to unravel. But the setting of the Dust Lands trilogy won’t wait for a spoiler-alert: The dystopia Saba has inherited is a world left by people called “The Wreckers” who are now extinct, their civilization long gone. The Wreckers could very well be us.

Hoot by Carl Hiaasen (Yearling, 2005)

Hoot is an oldie but a goldie. In his first book for kids (followed by the likes of Chomp and Flush), Hiaasen turns his humor to three middle-school children who are trying to save an endangered species of owl from an all-American pancake house called Mother Paula's.

While not explicitly climate fiction, Hoot still makes this list because climate change and mass extinction lurk in the background, making clear that our fates are inextricably linked to the flora and fauna around us.

How will Roy, Mullet, and Beatrice take on the cops, corporate thugs, and construction crews that are threatening the owls? Hiaasen’s indignation at our stupidity is as relevant as ever—only now it's not just Florida wildlife versus a pancake restaurant but the entire planet versus fossil fuels.

Life As We Knew It by Susan Beth Pfeffer (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2008)

The cover of Life As We Knew It apocalyptically reads, “the weather finally broke . . . for good.” And so it has. An asteroid has hit the moon, bringing it closer to Earth and unleashing a wave of natural disasters.

The point is not whether this could happen but that freak events are possible, and this book is a glimpse into what could happen when they do. “Here’s the funny thing about the world coming to an end,” Miranda, the book’s rural Pennsylvania heroine says. “Once it gets going, it doesn’t seem to stop.”

Told in diary entries, the book begins as the complaints of a self-absorbed and precocious teenager and mellows to a woman realizing the harshness of a world in climate winter. Will Miranda find a way out?

The Fog Diver by Joel Ross (Harper Collins, 2015)

The world is covered by a fog in which humans can’t survive, making them move to the highest elevation possible. A group of ragtag orphans operate an air-raft that lets the hero, Chess, dive down into the mists to scavenge for treasures they can trade for supplies. Born in the fog, Chess is the only one immune to the sickness it, and he has special sight that allows him to see in the fog. But his special abilities make him a wanted man in the eyes of Lord Kodoc, ruler of slums and all-around evil guy, who is hunting him.

The Fog Diver is fast-paced and exciting. Through the fog shine a few important parables: that we are the problem that caused the abysmal fog; that nature can thrive if left alone; and that this is the time to let tenacious young kids lead the way.

Also recommended: Survival Colony Nine by Joshua Bellin, The Lost Compass by Joel Ross, Parched by Melanie Crowder, and parts two and three of the Dust Lands trilogy by Moira Young.

Ages 15 to 18

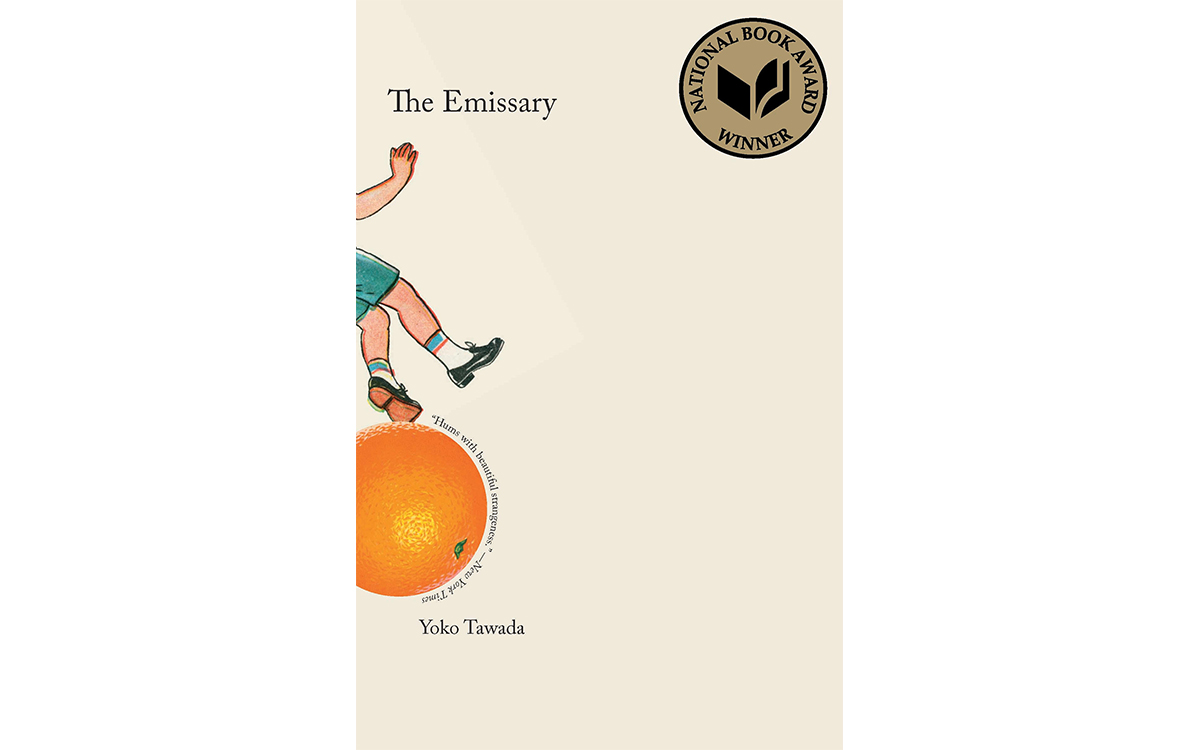

The Emissary by Yoko Tawada (New Directions, 2018)

Born in a country that is isolated and off-kilter, the children living in The Emissary are condemned to short, miserable lives. Japan has suffered some kind of trauma that has left it closed off from the rest of the world; its children are born frail and don’t make it to adulthood, while the adults keep on living.

In this awry world, both sinister and funny, we are introduced to the infant Mumei and his great-grandfather, Yoshiro. Author Yoko Tawada is a master at illustrating their lives; the tenderness and love between great-grandfather and grandson seeps through the pages.

But what will happen when Mumei is chosen as an emissary to tell the outside world what is happening? Will he make the journey? How will the world react to him?

The allegory is clear: Our children will inherit a far more hostile planet. Countries are closing off their borders already, and the number of refugees will only rise as more people are displaced by a changing climate. But we have our own young emissaries like Greta Thunberg. Hopefully, her fate will be different from Mumei’s.

The Highest Tide by Jim Lynch (Bloomsbury, 2010)

A Pacific Northwest bildungsroman, The Highest Tide traces a summer in the life of Miles, a Rachel Carson–worshipping, too-short-for-his-age boy who is deeply fascinated by the ocean and the multitudes of life in it.

When Miles finds strange sea creatures (a giant squid, a ragfish) washing up at a Puget Sound beach, he is mistaken for a prophet and made into a sensation by the local media. During an interview, Miles portentously tells a reporter, “Maybe the earth is trying to tell us something."

The Highest Tide will make young readers enamored with the oceans at a time they need it the most. Climate change is causing warming and acidification. Emaciated whales are washing up on the shores. Coral reefs are dying and algae are blooming. As the waters of Puget Sound continue to rise an inch a year, Miles and his town will experience the highest tide by the end of the fateful summer.

Author Jim Lynch populates his story with a sweet and sour ensemble of characters and manages to keep the spotlight squarely on the water while exploring quintessential coming-of-age themes of puberty and sexuality.

Midnight at the Electric by Jodi Lynn Anderson (Harper Collins, 2017)

Sometimes it takes a simple, quiet voice to show us not only what we’ve lost but what we can hope to gain.

Midnight at the Electric begins in 2065, in Miami, where 16-year-old Adri has spent her whole life watching as the waters rise higher and higher through the city. This is the lost world being left behind, and Adri has been chosen as one of the few colonists to eke out a new future for humanity on Mars.

But before she goes to outer space, her life will be linked to two people who lived generations before her: Catherine and Leonore. Through the letters that Catherine and Leonore wrote to each other, Adri will find a past she never knew she had and an unexpected family among two long-dead women.

Evocative and lyrical, Midnight at the Electric is as much history as it is future. When things go awry in the future—climate chaos, war, dust everywhere—we will have to rely on each other to make it through.

When Adri eventually leaves Earth, she hopes to get to Mars safely and once there, “We make something new, and we do it right. We pay attention.”

Orleans by Sherri Smith (Penguin Random House, 2014)

There is only so much devastation a place can take before it succumbs. The Gulf Coast in Orleans is that place. Hurricane after hurricane has blasted away the land and its people. After the storms comes the Delta Fever, an epidemic not unlike the Spanish Influenza: deadly, with no known cure. After the fever comes the quarantine, and the United States separates from the Delta States.

What the residents of the Outer States don’t realize is that people still survive, in primitive colonies, in the Delta. They just have to not mix blood types (A-positive and O-negative are segregated) to keep the fever at bay. Orleans is harrowing and dystopic but not so hard to imagine.

“You know, there used to be music here all the time . . . jazz and blues, zydeco. The kind of songs that made your heart sing,” an illegal mover of good between the two places says wistfully.

“Not anymore,” replies 15-year-old Fen, an O-positive blood tribe member who is living in the quarantined region. Soon, she will be on the run from blood farmers with her friend’s newborn, trying to give the baby a new life on the outside. This is a book as heartbreaking as it is uplifting. As a species, we are often terrible to one another, but author Sherri Smith insists that we can, and must, be kind.

Also rcommended: Not a Drop to Drink by Mindy McGinnis, Breathe by Sarah Crossan, After the Snow by S.D. Crockett, The Marrow Thieves by Cherie Dimaline, Ship Breaker by Paolo Bacigalupi, and The Carbon Diaries 2015 by Saci Lloyd.

Ages 19 to 22

New York 2140 by Kim Stanley Robinson (Hachette, 2017)

Kim Stanley Robinson is a science fiction master, and New York 2140 is among his masterpieces. Sometimes climate fiction can be dishearteningly dystopian, but not this title. The sea might have risen 10 feet in the 2050s and another 40 feet as 2100 approached, but the denizens of New York soldier on. The voices of eight of these—all residents of the iconic Met Life tower—tell an urgent story of a not-so-far-fetched New York.

How Robinson created a utopian vision of humanity amid the debris of all our bad choices is hard to say. Suffice it to say that this mosaic takes on much more than climate change, because resilience in 2140 is about people changing the system—political, financial, and social—to survive.

“In the eternal battle of men against the sea,” Robinson writes, “which antagonist was winning?” Read and find out.

South Pole Station by Ashley Shelby (Macmillan, 2018)

Cooper Gosling, our aggrieved and somewhat lost protagonist has earned the dubious honor of winning a National Science Foundation grant for the Antarctic Artists & Writers Program and is now living with the oddball personnel that populate a place where it is -54°F and the sun doesn’t shine for half the year.

South Pole Station is rife with workplace drama, as only this kind of atmosphere can be, and author Ashley Shelby has managed to write a novel that is both dark and hilarious. It is also filled with scientific detail that gives the reader a sense of what is happening without being, well, boring.

At times, it is eerily like real life, with the federal government of South Pole Station biased against scientific findings and the arrival of a scientist who claims climate change is a hoax. Heartwarming in the chilling cold, South Pole Station is an irreverent take on the misfits living at the end of the world, and how art and science can share world views.

American War by Omar El Akkad (Penguin Random House, 2018)

America has been waging oil wars for a long time now, but it’s now 2075, and in a country reeling from the impacts of climate change, the North has outlawed the use of oil. But the South refuses to abide by federal laws, and so it secedes from the Union to spark a second Civil War, which drives Omar El Akkad’s fast-paced and alarming debut novel.

In flooded Louisiana, Sarat is born and lives. The story follows her into the war, where she will visit some dark, unhappy places. The only joyous parts of the novel are Sarat’s memories: “My favorite postcards are from the 2030s and 2040s, the last decades before the planet turned on the country and the country turned on itself,” the prologue begins.

Akkad imagines what it would be like if all the horrors of war that America has unleashed across the world—drones, refugee camps, suicide bombers—were to come home, and in the process turn Americans against each other.

Blackfish City by Sam J Miller (Harper Collins, 2018)

While the premise of Blackfish City sounds like science fiction, the context is very much of the present reality. Humans have fled the flooded and burned-up world of climate chaos and used their technological prowess to build a floating city called Qaanaaq in the Arctic Ocean. The energy is renewable, the heating is geothermal, and everywhere you look there is a feat of engineering. Yet society remains unchanged.

Told through the perspectives of four struggling characters—Kaev, Fill, Ankit, and Soq—Blackfish City is a richly imagined story of technology and a reminder that technology can only take us so far when we remain the kind that refuses to play well with others. If the people who left the world behind continue to make the same choices in Qaanaaq, how long before it crumbles too?

Crime is on the rise, corruption is unabated, the rich stay rich and the poor remain poor. In the midst of this arrives a mysterious woman, Masaaraq, regarded as a messiah by some and an enemy by others.

Like Robinson in New York 2140, Miller subverts the hero trope here to show that Masaaraq alone as an individual is nothing and that the collective has no easy ways to form a just society is a post-apocalyptic world.

Also recommended: Who Fears Death by Nnedi Okorafor, Future Home of the Living God by Louise Erdrich, The Migration by Helen Marshall, Odds Against Tomorrow by Nathaniel Rich, Clade by James Bradley, The Floating World by C. Morgan Babst.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club