How Patagonia Surfed Around Death and Taxes

Founder Yvon Chouinard plans for a future without him

Photos by Campbell Brewer courtesy Patagonia

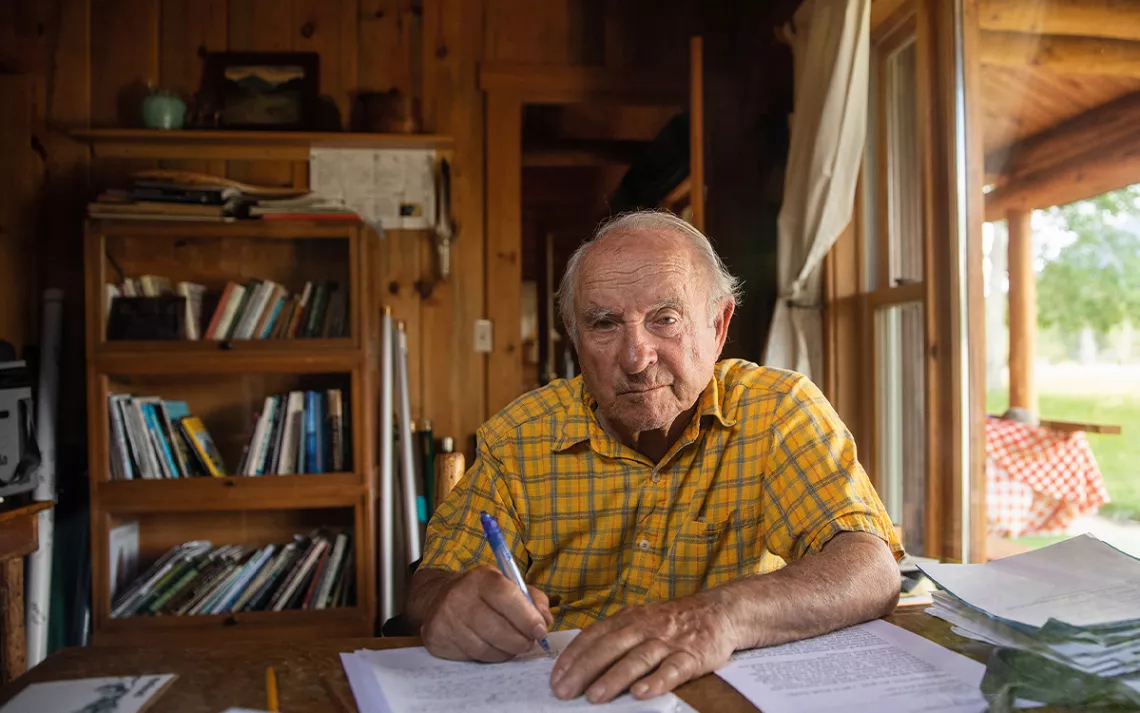

When 73-year-old adventurer Rick Ridgeway learned that his old buddy Yvon Chouinard was giving away outdoor retailer Patagonia to a nonprofit that will donate the company’s profits to environmental work, he wasn’t terribly surprised. Ridgeway has known Chouinard, the company’s 83-year-old founder, since the early 1970s, when the pair bonded during trips to climb and surf in remote places. Then, Ridgeway spent 15 years leading Patagonia’s environmental initiatives and public engagement. The company’s fidelity to green values, he said, was clear from the start.

“Patagonia’s always been one step ahead, out in the vanguard exploring new ways to do things,” Ridgeway said. “The company’s had that commitment since it started 50 years ago.”

On September 14, Patagonia made headlines when Chouinard announced that he was transferring 98 percent of the family-owned company—and all its nonvoting stock—to the nonprofit Holdfast Collective, an advocacy group with a mission to “fight the environmental crisis, protect nature and biodiversity, and support thriving communities.”

The remaining 2 percent—plus the voting power to guide the company—goes to the Patagonia Purpose Trust overseen by members of the Chouinard family. In Patagonia’s ebullient terms: “Earth is now our only shareholder.”

Patagonia projects that the Holdfast Collective will spend or donate $100 million each year, creating an overnight heavyweight among America’s environmental groups and philanthropies. Calling this the “biggest milestone in the company’s history,” Ridgeway estimated a ten-fold increase of the company’s current charitable donations. It’s a major windfall for the environmental movement. And it’s also a creative way to dodge two things that keep many aging founders awake at night: death and taxes.

During his time at Patagonia, Ridgeway saw firsthand the Chouinard family’s quest to secure the company’s legacy. “It was a real conundrum,” he said. “Not just for the tax consequences. The conundrum at its highest level centered around how to inculcate, into the structure of the company, its core values, so that those values would be preserved after the Chouinards were dead.”

Those core values include a longtime dedication to sustainability work. In 2002, Chouinard cofounded the charitable giving network 1% for the Planet, pledging Patagonia would give away 1 percent of annual sales to grassroots environmental nonprofits. (It will continue to do so.) A decade later, Patagonia became California’s first B-Corp, a certification for companies with environmental or social missions.

For entrepreneurs seeking to cement such legacies, “there’s a limited set of options,” said Stuart Hart, cofounder of the sustainable innovation MBA program at the University of Vermont. Hart said that for years Patagonia has explored many succession options. Going public and selling are two common routes. But each can mean losing control, Hart explained, adding that such a move is painful for many leaders. “This was the option that ensured the longevity and perpetuity of the mission for the company,” he said.

When news about the Patagonia transfer broke on the afternoon of September 14, public reaction had a joyous tone rarely linked to conversations about corporate restructuring. “BRB gonna cover myself head to foot in Patagonia,” tweeted publisher Lisa Lucas. Writer Rebecca Solnit tweeted that Chouinard was “annihilated as a billionaire; enhanced as a hero.”

Even as they applauded the move as altruistic, some observers also noted it would avoid massive tax liabilities for the Chouinard family. While the New York Times article that first reported the Patagonia story quoted a company adviser saying it brings the Chouinards “no tax benefit,” that’s incorrect, said Daniel Hemel, an expert in tax law and a professor at New York University School of Law.

“The Chouinards got a huge tax benefit from this,” Hemel said. By keeping control of just 2 percent of Patagonia, the family can contribute to political campaigns by proxy and steer the company while minimizing their tax liability on a $3 billion corporation, Hemel said. The nonprofit Holdfast Collective can use the company’s money for advocacy work. Crucially, its 501(c)(4) designation allows the collective to put money into political campaigns—something a traditional 501(c)(3) charity is banned from.

“If I give $3 billion to you, I’d owe $1.2 billion in gift tax,” Hemel said. “They figured out a way to give $3 billion away, having it not go to a traditional charity, and instead of paying $1.2 billion in gift tax, they’re paying $17 million in tax. So they cut their gift tax bill by more than 98 percent.”

This does not, Hemel stressed, undercut the impact of the move. The Chouinard family is giving up a vast fortune. Their tax savings translate to even more funding for environmental advocacy. The family is both playing by the tax rules and working to save the planet. Chouinard is, famously, a “reluctant billionaire,” and he really does want to save the planet.

Still, by ploughing the company’s earnings into a nonprofit supporting political campaigns, the Chouinard family has drawn attention to a part of tax law that many experts find disturbing. “The ability to give stock to a c-4, then have the c-4 cash out of dividends and capital gains tax-free, that can be used for good or ill,” Hemel said. Last month, The New York Times reported that financier Barre Seid used a similar move to donate $1.6 billion in company shares to the conservative Marble Freedom Trust helmed by dark-money guru Leonard Leo. Such donations divert funds from the government to the hands of powerful individuals. And they can bring a large—and largely opaque—infusion of cash into politics.

“I don’t think that’s an argument against what the Chouinards did. If I were in the Chouinards’ position, I hope I’d be generous enough to do the same,” Hemel said. "It points out that there are problems with our tax code that we should fix. But there are also threats to our climate that we should address.”

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club