How a Rare Native Plant Preserve Sustains One Texan Woman’s Legacy

The rise of an unlikely naturalist and fierce preservationist

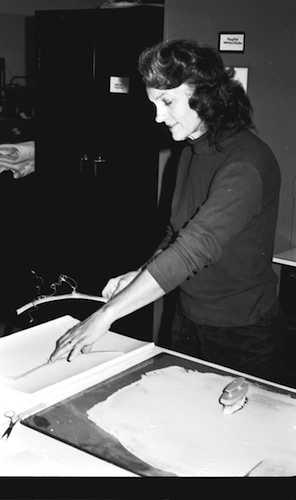

Photos courtesy of Sophia Dembling

To be honest, I don’t recall how I found the Watson Rare Native Plant Preserve back in 2011. Google, probably. My husband and I were planning a trip to South Texas, and the preserve near Warren, Texas, turned up in my research, so I put it on our itinerary. I’m no botanist, but I do like a pretty place.

I remember clearly that April visit, though. We parked by the not-so-easy-to-find entrance and walked past a homemade sign admonishing “Do Not Disturb Plants or Wildlife” and “No Fire Arms” and into a quietly magical landscape.

I remember clearly that April visit, though. We parked by the not-so-easy-to-find entrance and walked past a homemade sign admonishing “Do Not Disturb Plants or Wildlife” and “No Fire Arms” and into a quietly magical landscape.

Southeast Texas in its natural state is a dense tapestry of 10 ecosystems, from towering long-leaf pine forests to cypress bogs. Carnivorous plants and cacti dwell alongside orchids and azaleas. We were alone on the 10-acre property, and the path led us through a pine forest rising from a bed of ferns to a wooden boardwalk with flowers peeking through its slats, past cacti, fields of pitcher plants and white-top sedge, and a small pond. At the end of the boardwalk stood a somewhat dilapidated A-frame cabin.

The place was enchanting, and I knew little about it or the woman responsible. Had I been quicker on my feet, I might have been able to meet Geraldine Watson, who was living in Austin when I visited her preserve; she died almost exactly a year later, at 87. When I finally started digging into her story, I found the kind of character Texas legends are made of. Watson’s legacy includes helping establish Big Thicket National Preserve—the nation’s first—and carving out her own little patch of preserved South Texas. Before her death in 2012, Watson formed a nonprofit and deeded the property to it, ensuring the preserve would remain open to the public.

“The intention was for any individual person not to own it,” says Pauline Singleton, executive director of the nonprofit. “She was trying to make sure somebody would keep it from development. She always welcomed visitors. She considered herself kind of an ambassador to the natural world.”

Born in 1925, Watson moved to South Texas from Louisiana as a child. Both her mother and father took her exploring in the woods, teaching her about the flora there and instilling in her a passion for the complex region. Watson went on to enroll in botany courses at Lamar University, but that was just the beginning of her education; she was mostly self-taught. “That’s what was amazing,” says David Lewis, a retired chemist who became friends with Watson in the 1970s. “She took some botany courses, and she interacted with ecologists and botanists. She went to what I call the ‘school of no credit.’ She really knew the ecology like no one else. She was at the forefront of figuring out what was going on in the preserve.”

Born in 1925, Watson moved to South Texas from Louisiana as a child. Both her mother and father took her exploring in the woods, teaching her about the flora there and instilling in her a passion for the complex region. Watson went on to enroll in botany courses at Lamar University, but that was just the beginning of her education; she was mostly self-taught. “That’s what was amazing,” says David Lewis, a retired chemist who became friends with Watson in the 1970s. “She took some botany courses, and she interacted with ecologists and botanists. She went to what I call the ‘school of no credit.’ She really knew the ecology like no one else. She was at the forefront of figuring out what was going on in the preserve.”

Watson launched a collection of Big Thicket vegetation for Lamar (which later moved to Rice University). “Her outline of the Big Thicket ecosystems became the basis for all discussion for people supporting preservation legislation,” says Maxine Johnston, a fellow activist, now 88 and living in Batson, Texas.

It was the 1960s, and longleaf pine forests were threatened by industry and logging. Seeing the pristine areas mowed down with no forethought ignited Watson’s activism. She became an insistent voice of the preservation movement, while Johnston was a mostly behind-the-scenes force. Watson authored a column about the flora and fauna of the Big Thicket for a short-lived newspaper called the Pine Needle, which was published by a Silsbee attorney in part to promote the establishment of a national park in the Big Thicket. She created slideshows and presented on South Texan flora before garden clubs, civic clubs, professional societies, and government leaders—including then senator George H.W. Bush and then congressman and Appropriations Committee member Charlie Wilson.

The goal was a national park, and Watson and Johnston testified in Congress several times. The fight to preserve the Big Thicket was contentious, with lumber companies riling up locals with “outrageous claims about loss of taxes, taking homes, schools closing, job losses in the forest industry, ad infinitum,” Johnston says. “Geraldine and many others responded with logic and data that refuted the nonsense.” This, she says, was where Watson earned her reputation for being “prickly.”

Watson was a complex individual and perhaps not always likeable, which might just be par for the course. Serious activism requires singlemindedness, stubbornness, a thick skin, and a firm belief in the righteousness of your cause—all admirable qualities that nonetheless may or may not make you a person people are glad to see arrive.

Not that her friends speak ill of her. Singleton, who first met Watson in 2006, says, “Outspoken, yes. Certainly. Ornery, no. I found her to be welcoming and eager to share. A caring person. I guess the crankiness would come out when she encountered people who didn’t care about the things she cared about.”

“Outspoken is an understatement,” Johnston says, while Lewis remembers the two women together as formidable. “You didn’t want to get on their bad side.”

Watson had a husband and five children, and in a 1999 interview said that her activism caused her family great distress. “Everybody hated my guts,” she said. “If I had known then what it would mean to my family, I would never have gotten involved.”

She said she was spit on, and her children were ostracized. “Perhaps Geraldine was a little more vocal and confrontational than others,” Johnston says. “I guess she believed strongly in efforts for preservation, and to some extent her dedication impacted her home life.” Lewis thinks her husband, Earl, probably would have been just as happy to have a quiet, homebody wife.

But Watson and other conservationists prevailed when, in 1974, Gerald Ford signed into creation the Big Thicket National Preserve. The preserve has grown over the years to encompass more than 112,000 acres.

Watson served as the park’s first naturalist and catalogued its plants—which currently include more than 1,300 species of trees, shrubs, vines, and grasses—including four of the five species of carnivorous plants found in the United States. She also mapped out its ecosystems, and laid out the park trails. Her book, Big Thicket Plant Ecology (University of North Texas Press), published in 1979, is now in its third edition.

After about 15 years, Watson left the National Park Service. Johnston blames personnel changes and employee-qualification grades; Singleton and Lewis both think that Watson and the NPS disagreed on management techniques—particularly Watson’s commitment to burn management.

In the meantime, though, she’d found and purchased a piece of property she’d discovered while bird-watching near the town of Warren. Over time, she’d purchased, piece by piece, 10 contiguous acres, creating what she called the Watson Long Leaf Pine Preserve.

There she built with her own two hands a four-level A-frame cottage, which she’d also designed herself. Her family was “not in sympathy with my goals,” she wrote in her application for nonprofit status for the preserve, so she did everything herself, with no electricity and only hand tools—hand-sawing oak beams and rafters.

“I don’t know how she managed to build that cabin,” Singleton says. “The lumberyard would not even ride the truck up the driveway [which was in bad shape]. They would just dump the wood at the end.”

Then, in 1982, a neighbor lost control of a trash fire and that house burned down. Shortly after that, Earl died. But Watson rallied and rebuilt, making a concession to her age by having electricity installed and using power tools. Watson, also an artist, used it as a studio and lived there part-time for many years, although her primary residence was in Silsbee. In 2003, she published a more contemplative book than her first, Reflections on the Neches: A Naturalist’s Odyssey Along the Big Thicket’s Snow River (University of North Texas Press), which she and her daughter Regina illustrated.

Singleton, also a committed conservationist, met Watson after coming upon a newspaper clipping she’d saved of an interview with Watson about the preserve. The article included Watson’s telephone number and an invitation for anyone to call and visit. So Singleton arranged to see the preserve in early June 2006.

Like me, she felt like she’d stepped into “a botanical wonderland.” Unlike me, she knew what she was looking at.

“I had roamed around a bit in the Big Thicket in the eighties,” she says. “And then a period of 15 years or so went by when other things kept me away. When I did return, many places had become taken over by brush, mowed to death, bulldozed, converted to cow pasture, or otherwise altered.”

The reasons are many, she says, including budget constraints within the National Park Service, but also roadside management. “There was a stretch of road between Kountze and Thicket where I once spent hours photographing grasspink orchids, pine-woods rose-gentians and other wonderful wildflowers. No more! They adhere to an obsessive-compulsive mowing schedule that does not allow many of these plants to bloom, and certainly gives them no opportunity to reproduce.” Feral hogs are also a problem, says Singleton; and the inexorable march of development. “The growing population of Texas is a little bit like a runaway bulldozer in the Louvre.”

But at Watson’s preserve, she saw pinewoods, rose gentians, snowy orchids, “and the mostly spent grasspink orchids,” she recalls. “I was delighted to find a place where they still flourished.”

As she approached the house, Singleton saw Watson, then 81 years old, having coffee with a friend on the upper deck. Watson waved Singleton up to join them, then took her on a tour, pointing out plants and flowers and explaining her controlled-burn management technique, which she had done for many years.

“Geraldine burned her place pretty frequently,” says Lewis, who leads free educational walks on the preserve. Because long-leaf pine requires open savannah, “without fire you don’t have long-leaf pine.”

Watson’s preserve includes seven species of orchids, 10 species of ferns, trilliums, violets, and four types of carnivorous plants. “She didn’t know that Ascepias rubra was present until she cleared the land and began to use fire as a management tool,” Singleton says. The grasspink orchids also flourished in the winter burns. Watson introduced red/orange few-flowered milkweed to the property, and white-flowered milkweed. “I have seen it growing in the area, so I consider it a plant that belongs there,” says Singleton. She also planted snowy orchids. And, Singleton says, “The next time I visited, the orange Chapman’s orchids were in bloom. I hadn’t seen them in years.”

Singleton, who is now 73, visited the preserve many times after that first day, and the two women became friends. Now Singleton runs the nonprofit that keeps the preserve going, with funding coming mostly from a handful of “generous individuals,” Singleton says.

Today, the old hand-painted sign has been replaced. Geraldine’s cabin is still standing, but in disrepair. “We’ve been in a holding pattern, trying to just prevent further deterioration,” Singleton says. “I hope that someday we can obtain funding and do all the repairs that it deserves.” Much of the preserve maintenance is done by volunteers, and includes fighting exotic and invasive plants; endlessly repairing the old boardwalk; mowing and maintaining trails; servicing the porta potty; and annual burns.

The preserve seems to have enjoyed the soaking Hurricane Harvey gave it, Singleton says, and five years after her death, Geraldine Watson's wonderland lives on and remains free and open to all.

“That was her wish,” Singleton says. “She wanted to share it.”

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club