Just How Scientific Is Your Favorite Board Game?

Fact-checking the tabletop science game boom

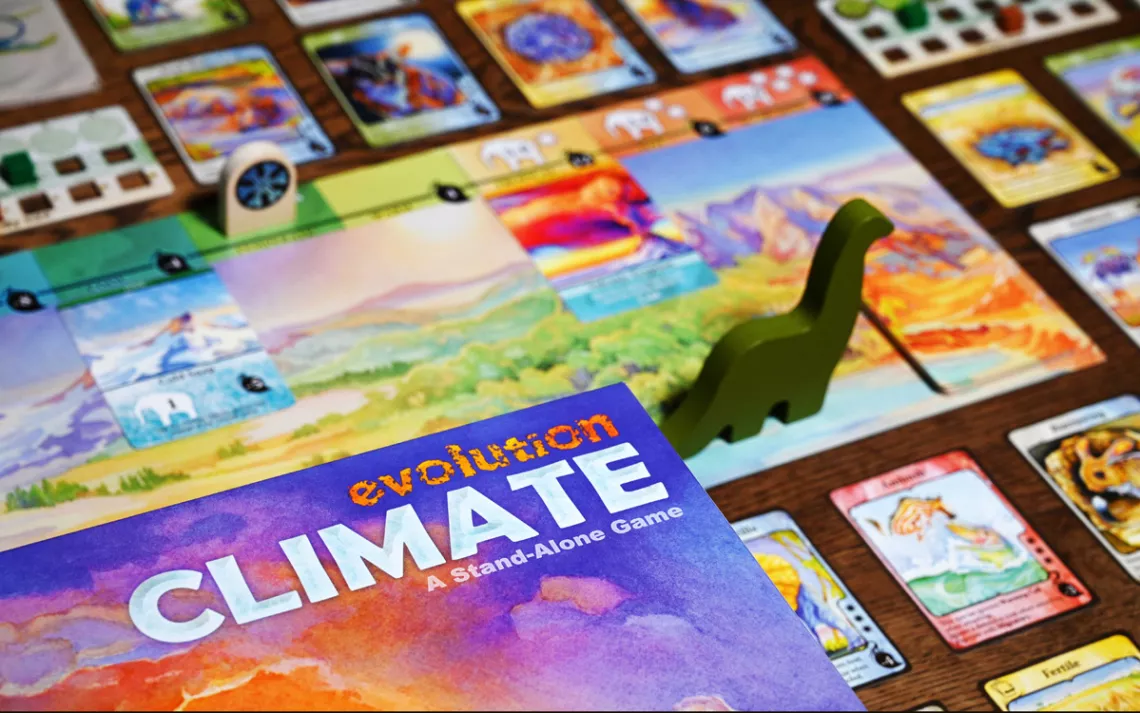

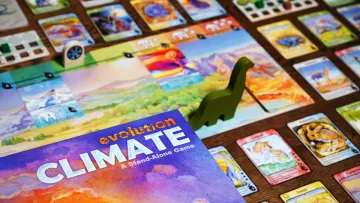

The game Evolution. | Image courtesy of North Star Games

Board and card games (collectively known as “tabletop games”) are going through what some people call a renaissance and what I like to call a “Cambrian explosion.” The number of games published per year has skyrocketed over the past two decades. Most of them are fantasy, sci-fi, and history themed, but I’ve been surprised to find how many focus on science and ecology. In 2019, Elizabeth Hargrave’s bird-themed Wingspan became an instant best-seller, critical darling, and crowd favorite, selling over 750,000 copies—a mind-boggling number for a board game produced by an independent game publisher.

As a science writer and an amateur game designer, I’ve found that nature is an incredible well of potential “mechanics” (the actions players perform in games) and “themes” (the settings or topics of games). But drawing inspiration from reality also creates a responsibility to get it right scientifically—and that’s not always compatible with creating a game that is playable and fun.

Gamifying anything requires simplifying, abstraction, and lots of omissions. A poorly designed game can leave players with a perception that is the opposite of the truth. So I set out to play and analyze seven popular scientific board games that focus on ecology and climate to find out a) how scientific they actually are and b) how fun they are to play.

A note: when I set out to explore ecologically themed board games, I found abundance. I regretfully wasn’t able to cover Parks (2019), Photosynthesis (2017), Renature (2020), Kyoto (2021), Ocean Crisis (2019), Biome Builder (2017), or Cascadia (2021) for this article, but they all easily fit the criteria for this list, and I encourage you to try them.

Publisher: Genius Games

Recommended ages: 8–10 and up. (Note: Recommended ages are far from an exact science, and publishers vary widely in what ages they print on the box. In this article, I’m using a combination of the Board Game Geek "community" estimates, which are crowdsourced, and personal judgment after playing these games.)

Number of players: 2–6

Duration of play: 10–20 minutes

Ecosystem (2019) is a card game designed by independent designer Matt Simpson. It’s published by Genius Games, which specializes in science games that can be played in educational settings, like classrooms, as well as informal game nights.

Gameplay-wise, Ecosystem is very simple: Each player receives a hand of cards featuring illustrated woodland creatures, which they then deploy to build up a personal “ecosystem” of cards on the table in front of them. When the game is over, each player’s ecosystem receives points, according to criteria that loosely resemble “ecosystem function.” Bears next to bees or trout = points. Trout + streams + dragonflies = points. Foxes next to wolves or bears = no points, because the bigger carnivores outcompete or possibly eat the foxes.

Genius Games project coordinator Steve Schlepphorst, who worked on Ecosystem’s development team, says one of the game’s strengths is its ability to mirror how scarcity functions in living ecosystems. “You can just explain the rules to a player and then send them to play, and they will quickly discover the sort of pitfalls of having a ton of eagles but nothing for the eagles to eat,” he says.

When it came to science though, I personally wanted more. The ecological relationships between the organisms are only discussed during the point-scoring phase, and a lot of the who-eats-who dynamics the game depicts are fairly obvious.

That said, Ecosystem fills an important niche as a quick, simple way to introduce a new gamer to “card drafting” (the process of picking a card you want and then letting another player pick) and “tableau building” (which is when you need to arrange a set of cards or tiles on the table in front of you). It’s also simple enough and quick enough to work as a middle school science classroom activity, which is a feat in itself. Experienced gamers, though, are likely to be bored.

Publisher: Weird City Games

Recommended ages: 10 and up

Number of players: 2

Duration of play: ~30 min

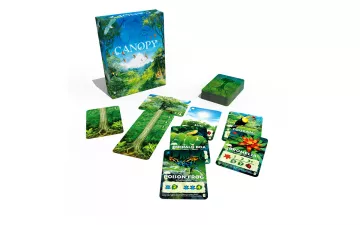

In Canopy, two players take turns drafting cards from facedown piles to add to a “patch of rainforest.” Each card features a plant, animal, or type of weather that you might encounter in the Amazon rainforest, and each has a unique effect when deployed.

For example: drawing a single fire card forces a player to get rid of one card from their forest at the end of the “season.” But draw three fire cards and both you and your opponent are losing forest. “The fire is an interesting card,” says Canopy’s designer, Tim Eisner. “Fire in the natural environment can be helpful, and a lot of plants need that to germinate their seeds, but also obviously, it does damage to people.”

Like Ecosystem, Canopy was designed to be a “gateway game” that is accessible to non-gamers and kids while teaching them board game skills like spotting synergistic card effects. However, Canopy is a more complicated game than Ecosystem, even though beginners can play it. As a season (each round is a season in the forest canopy) comes to an end, it becomes considerably harder to decide which cards in the piles are “best” for your forest.

That challenge has its benefits—the game condenses a system of complex interactions and trade-offs into a simple card-drafting format, and that’s pretty cool. But if one player has experience playing card-synergy games, and the other player is a newbie, the game could end up pretty lopsided.

Eisner, the game’s designer, considers it to be more science-inspired than science-based. But when we talked shortly before Canopy’s release, he said that it did grow out of his own concerns about the climate. “I was thinking for a while about stepping away from board games to do a bit more direct work on climate change,” he said. “But then I realized, through board games, I have a platform.”

Eisner’s ecological concerns extended to Canopy’s production. He also set out to manufacture it without using any plastic—not easy in a field where the parts are often bagged and shrink-wrapped. "Getting the first sample from the manufacturer and not having any plastic in it was very satisfying and gratifying to me,” he said. “It’s still producing a lot of things and sending them all over the world, but it’s nice to make an impact on that level.”

Eisner hopes other publishers will take similar steps. “The [profit] margins in board games are pretty small to start with,” he said, “and people are also somewhat resistant to change.” Now that Canopy has pulled it off though, he hopes that others will follow.

Publisher: Self-published

Recommended ages:10 and up

Number of players: 2 or 4 (one of Nunami's quirks is that you have to play it with an even number of players)

Duration of play: 20–40 minutes

Nunami is a game about humans and wildlife coexisting on a vast tundra. It’s also the first commercially available board game designed by an Inuit person—educator and graphic designer Thomassie Mangiok. “I love board games and video games and whatnot,” says Mangiok. “I thought it was a great medium to share our values.”

Specifically, Mangiok was tired of the idea that animals were lesser than humans. “For as long as I can remember, I heard about respecting animals, living with animals, living in our environment, and being healthy,” he says. “When we adapted to general culture, we were taught through a Christian religion that animals were made for us, that we’re higher beings.… I didn’t like that. I always believed that we’re just creatures, equal to anything out there.”

In Nunami, players add triangular cards representing humans, wildlife, ice, or sand to a board made of rearrangeable hexagons. The goal is to earn plastic chips representing “game points” by having your color be the majority color on a given hex. Oftentimes the way to win Nunami is to spread out and share hexes with other types of cards, mimicking the way ecosystems spread out across the vastness of the tundra.

Nunami doesn’t take long to play, but it took me considerably longer to learn. There are several rules about which cards can be placed where, and some of the wording in the English rulebook was a little bit ambiguous. (Nunami also comes with rulebooks in French and Inuttitut, but, unfortunately, I don’t read either language.) But once you know how to demo a turn, you can teach others in a few minutes.

I really adore playing Nunami, because it’s competitive and lively yet easy-going. Mangiok’s unique perspective comes through in the game’s details: The cards and pieces are waterproof and lightweight enough to tuck into a backpack for a hike (though the 13.5" x 12" box that they come in might be unwieldy). The cards feature adorable illustrations in three different styles—Mangiok’s minimalist graphic designs, anime-like blue cards drawn by his daughter, and line illustrations drawn by his mother on the special-ability-granting Inua cards.

Overall, there are many similarities to other tableau-builder games, but there are also subtle mechanics differences that give Nunami a unique feel. Players may score by occupying more slots in a hex, but if a hex is too dominated by humans or wildlife, the hex doesn’t count for scoring, and nobody wins it. Most tabletop games reward players for doubling down on a single strategy or controlling specific areas of the board, but Nunami rewards balance and coexistence. This value system gives it a different vibe than strictly player-versus-player games, like chess. Nunami is one of the games I show off to nongamer friends when I’m trying to convince them, “Look, board games have massive amounts of untapped artistic potential.”

Some people might argue that Nunami isn’t really an ecology game, at least, not in the same way other games on this list are, and there’s some truth in that. Ecology, the scientific discipline, is very much a Western way of thinking, and Nunami really isn’t about that. Instead, it presents a distinctly Inuit way of thinking about finding balance between humans and neighboring creatures. In a medium dominated by games that center around extraction, exploitation, and fighting to occupy locations, I found Nunami to be very refreshing. And with its emphasis on humans and wildlife coexisting, I’d argue it is a game about ecology, albeit in a very abstract way.

Western thinking tends to divide humans from nature in a very “us versus them” way, and most games about wildlife echo that (false) separation, often omitting human presence from the game entirely. Nunami doesn’t. Instead, humans and wildlife must navigate each other’s presence and thrive alongside each other.

Also, quite frankly, tabletop games, especially “strategy games,” are overwhelmingly steeped in Western worldviews, but the medium is capable of much more than that. I personally want to see many more games from BIPOC creators that offer alternative perspectives.

Publisher: AEG (Alderac Entertainment Group)

Recommended ages: 10–12 and up

Number of players: 2–5

Duration of play: 45–75 minutes

Following on the heels of Wingspan (2019), Mariposas (2020) is the second published game by Elizabeth Hargrave. In it, players help monarch butterflies migrate from Michoacan in Mexico to summering locations across eastern North America and back again.

Hargrave told me that the idea for making a monarch migration game came to her while she was reading Barbara Kingsolver’s novel Flight Behavior, where monarchs turn up at an unexpected location along their migratory pathway. “My game design brain started to think, ‘Oh, you could have butterflies moving on the map,’” Hargrave said.

The game covers the entire migration, which outlasts the lifespan of a single butterfly. As the rulebook puts it: “No single monarch makes the round trip.” Instead, players must guide their butterfly tokens to milkweed locations on the boards, where they can cash in their flower tokens (representing the “nectaring up” phase of migration) and spawn the next generation, which will continue the journey. Players earn points along the way by collecting life-cycle cards and traveling to certain locations by the end of each “season.”

Hargrave says that she never cared all that much about games with fantastical themes. Instead, her game designs reflect her interests as a birder, mushroom hunter, and general nature enthusiast. (She tuned in for our Zoom conversation with her name still displayed as “Mycological Society of Washington, DC.”)

The real-world decline of monarch populations is only indirectly represented Mariposas gameplay. The milkweed locations are fixed points on the map. Human cities mainly serve as landmarks, and several of them have helpful “sanctuary” hexes that allow players to pick up life-cycle cards, such as “caterpillar” and “chrysalis.” The rulebook does include a stark infographic about the monarchs’ decline and points Mariposas enthusiasts toward resources like the Monarch Watchers.

Hargrave hopes the human-planted waystations on the game board will help raise awareness about the decline of milkweed and other wildflowers that monarchs and other pollinators eat. “We’ve lost a lot, a lot of that plant matter that they really rely on,” Hargrave says. “Monarch Watch has a program called Monarch Waystations, really encouraging people to plant all of the nectar plants and milkweeds the monarchs need along the way, because so many of the wild spaces where those plants would normally grow have been developed.”

As a game, Mariposas struck me as a throwback to classic race-across-the-board games like Candyland and Chutes and Ladders, but with much more strategy involved. It allows (and even encourages) quite a bit of meandering and back-tracking, trying to land on the ideal flower or waystation. What most impressed me about it was the way its “table presence” sells the vastness of the monarch migration while still fitting on a small dining table. The board is quite large, while the butterfly tokens are very small and the hexagonal layout of the wildflower patches make it impossible for the butterfly tokens to travel in straight lines. Though the profusion of orange and pink flowers on the board can look overwhelming in photos, the game is gorgeous in person and easy to explain to nongamers.

Curiously, even though the vast majority of board games are about things moving across some sort of map, Mariposas is the only tabletop game I know of about a seasonal migration of nonhuman creatures, and I’d really like to see more of that. Animals’ perambulations are one of the main ways our biosphere moves biogeochemical resources around, and it seems like a natural entry point for future games.

Publisher: Grand Gamers Guild

Recommended ages: 10–12 and up (while the box says 10+, I think that’s optimistic, and Board Game Geek users say 12+)

Number of players: 1–5

Duration of play: 60–90 minutes

Out of all the games on this list, Endangered (2020) is the one I’d most recommend to someone who is dipping their toes in the water of the board game renaissance. Designed by Joe Hopkins, Endangered is a cooperative game (“a coop” in gamer terms). If you’ve never played a coop board game, I highly recommend it—they are a completely different species from Monopoly or Scrabble. “In a competitive game, there’s one person that wins,” Endangered’s creator Joe Hopkins said. “That person won. Good job! Everyone else lost. In a cooperative game, either everyone wins or everyone loses. So you’re all working together.”

In Endangered, players try to prevent the extinction of an endangered species, represented by adorable animal-shaped “meeples.” Each player takes on the persona—philanthropist, environmental lawyer, lobbyist, TV wildlife show host, or zoologist and use “action” cards and dice to take short-term actions like cleaning up habitat, while working to persuade UN ambassadors, represented by facedown cards, to pass legislation protecting the species long term. Each ambassador card has a unique criterion that has to be met to secure the ambassador’s “vote.” Because the ambassador’s goals start out unknown, players spend a lot of time trying to decide which tasks are most urgent and how to divide resources between managing environmental impacts and negotiating politics. It plays in one to two hours offering lots of opportunities for around-the-table debate and collaboration.

According to Hopkins, conservationists from the Center for Biological Diversity were recruited as early games testers, and Endangered’s “scenarios” for saving different species are inspired by real-world efforts—how easy it is to save a particular species is affected by factors like the animal’s mating habits and habitat, for example.

The game is unusual for the pathos it generates. “Endangered is a game that is very emotional,” says Hopkins. “During the game, it’s really like, ‘Ohmigod, we just lost a baby tiger!’ and really, no, it’s just a piece of wood.… But people get emotionally attached when you roll to get a baby.”

I agree. When an environmental destruction tile slams down and kills a baby tiger, it stings. I can safely say that Endangered provoked a lot more swearing from me than any other game on this list.

It’s rare for a board game to have that kind of emotional heft, and designers often try to steer away from “feel-bad” moments. But the reversals between “feel-good” or “I think we’re winning!” moments and moments where everything falls apart is what gives a story narrative weight. So it’s fitting that a from a narrative-driven genre like coop would come closest to replicating real-world political problems in tabletop form.

Hopkins did sacrifice some scientific accuracy in order to make the game more fun to play. “In the real world, moving animals is actually frowned upon,” Hopkins explained. “It’s better for them to stay in their original habitat.… But that moving aspect is an important piece of this game in order to get the animals to mate and to keep the animals safe from the oil spills.”

Endangered uses inclusive language and artwork, and the fact that a board game about environmental conservation exists (and happens to be excellent) is a major step. Its gameplay highlights the many actions ordinary people can take to help imperiled megafauna. And, as a game, I absolutely love it.

Now that playing Pandemic (2006) has become very emotionally fraught, we kind of need another midweight coop with high stakes, deep strategy, and an accessible design to step into Pandemic’s role as the “gateway” game that introduces nongamers to strategy coops. Endangered fits that niche brilliantly. (Caveat: Some gamer friends I’ve played Endangered with felt the game would be a bit too difficult for nongamers; however, I maintain that anyone who can wrap their heads around Wingspan should be able to parse this as well. Also, as a coop game, it lends itself to an “experienced gamers teach the nongamers” vibe.)

My main criticism of Endangered would be that Indigenous and other communities that live alongside tigers and other endangered species are largely absent from the game—instead, all the roles available to players are those of rich, powerful, educated people who can fly around the world and deliver petitions into the hands of UN ambassadors. While the game’s artwork depicts many of these environmentalist characters as nonwhite, I still felt the absence of local stakeholders. Local communities often play pivotal roles in conserving species.

I raise this issue not to dissuade people from trying Endangered, but because I don’t want it to become a recurring blind spot in games about conservation and climate change. My hope is that in the next few years, we’ll start seeing conservation games that include real-world scenarios like Indigneous-led land management. It would also be incredible if board games’ player agency and interactivity—which set them apart from all other narrative forms—can be leveraged to start discussions about climate justice or environmental racism.

Still, Endangered is one of my favorite games that I’ve tried this year, and I’d recommend it to both avid strategy gamers and the tabletop-curious.

EVOLUTION: CLIMATE (2016) & OCEANS (2020)

Publisher: North Star Games

Recommended ages: 12 and up

Number of players: 2–6

Duration of play: ~60 minutes

Evolution: Climate was one of the first games I bought when I started my own game collection. Since the debut of Evolution in 2012, followed by Evolution: Climate (2016) and a stand-alone spinoff called Oceans (2020), the series has sold over 300,000 copies and garnered good reviews from both game designers and evolutionary biologists. Dominic Crapuchettes, the game’s lead designer, adapted it from a game designed by a Russian teacher for use in biology class. “What makes a good simulation doesn’t necessarily make a good game,” Crapuchettes says, but he was taken with the way adapting a “species” changes the overall system dynamic of the game and decided to streamline it for a larger audience.

Like Wingspan, the Evolution games are “engine-builders,” where the entire game relies on finding combinations of cards that amplify each other’s effects. Players draw cards, which they use as “traits” or discard to manipulate the available food supply, increase their species’ population or body size, or start a new species. The species feed either by taking plant tokens from the “watering hole” or by attacking other species. The player whose species have managed to eat the most food tokens at the end of the game wins.

This competitive struggle for survival can make Evolution a brutal game. Crapuchettes took note of the success of family-friendly strategy games with animals that were challenging but didn't make kids cry (read: Wingspan) and created Oceans to appeal to that demographic. In Oceans, for example, players can’t eat other players’ species into extinction (at least not directly). Population growth and feeding work a bit differently in Oceans than they do in Evolution, but the goal is still to get food and avoid extinction.

Oceans is still rooted in biology, but it has fantastical elements—all the Evolution games are technically set in a parallel Earth where other forms might have evolved. (Despite its name, Evolution: Climate has nothing to do with real-world anthropogenic climate change and everything to do with hypothetical paleoecology on a parallel world.) In addition to a core set of “Surface” trait cards, Oceans adds even more fantastical and sci-fi elements through the Deep Cards, which provide unique but extreme abilities. “The Deep is the unknown, and these are the things that have yet to be discovered by science,” Crapuchettes says. “And we could lean in a lot into people’s imagination there. What I wanted to do artistically was invoke that sense of wonder.”

Oceans is a delight to play, but Evolution: Climate, which is available as both an expansion pack for Evolution and as a stand-alone, is still one of my favorite games.

I can’t help it; I like the brutality. But probably not for the reasons you think. The whole series, and particularly Evolution: Climate, has a peculiar quality—the more you know about biology and how ecology creates selective pressure on animals, the more you can see the biology built into the game.

To a biology major, the fact that a player wins Evolution by adding up population, body size, and amount of food consumed is a clear reference to scientific models that use “biomass” as an indicator of how well a species is doing. Evolution players often run into scenarios where one player adds a defense trait to their herbivore, and then another adds a hunting adaptation to their carnivore, thus causing the first player to add another defensive trait, and so forth. These sequences mirror what evolutionary biologists call the “Red Queen Hypothesis,” where predators and prey are locked in a perpetual arms race, with the evolution of new traits in one forcing new traits to arise in the other. It’s one of the best manifestations of a scientific phenomenon in game form that I’ve ever seen.

But what pushes Evolution: Climate over the top in my personal ranking is the way it depicts ecological collapse. Much like real ecosystems, these games spread species out across different niches. If there are too many carnivores or too many herbivores on the table, food supply tends to run out, leading to mass die-offs.

This phenomenon can happen in all the Evolution games, but it happens most frequently in Climate, because Climate adds a “climate board” that players can steer toward colder conditions (with less plant food, which is good for carnivores), warmer conditions (more plant food, good for specialized herbivores). Apocalyptic events like asteroid strikes are also a possibility in Climate–but not the other Evolution games.

In Oceans, extinctions only happen during the “population aging” phase of the player’s own turn (as opposed to immediately after attacks by other players), making extinctions much rarer and less of a “feel-bad” moment. This change will make the games more enjoyable and accessible to many. Crapuchettes notes that Oceans features even more cards that reflect ecological connections between species, such as Parasitism and Whale Cleaner. Food scarcity and shifting game conditions remain core parts of the Oceans experience. The game incorporates the same scientific concepts as its predecessors but does so in a gentler, more traditionally board-game-like way.

But my personal preference is for games with fewer procedural rules and more immersion. I’ve been a fan of evolutionary theory far longer than I’ve been a fan of tabletop games. For weirdos like me, who love biology because it is both patterned and chaotic, brutal yet nurturing, and all those wonderful contradictions, well, we can still play Evolution: Climate.

CO2: SECOND CHANCE (2018)

Publisher: Giochix.it & Stronghold Games

Recommended ages: 14 and up

Number of players: 1–4

Duration of play: 60–180 minutes

Vital LaCerda’s CO2: Second Chance is by far the heaviest game on this list in terms of the game’s difficulty and complexity and the only one that explicitly deals with the global climate crisis. Interestingly, it’s also one of the most optimistic games on this list.

CO2: Second Chance is an updated and, I think, much-improved version of CO2 (2011). In both incarnations, players take on the role of green energy companies who are racing to build clean energy infrastructure before the titular CO2 meter hits 500 ppm, ending the game. (The game can also end if players fail to achieve enough environmental goal tiles by each “decade” end.)

Each player/corporation receives a couple of secret individual goals to meet. Most of the action consists of proposing, laying groundwork for, and building green energy plants over the course of five decades. (If you’re really good at the game, that is. My game group usually wipes out in the second or third decade.) To achieve that, players have to acquire resources—most notably by manipulating the global CEP (Carbon Emissions Permit) market and by moving scientist meeples between projects and conferences. Any dilly-dallying, failure to plan ahead, or backstabbing is almost guaranteed to result in a loss for everyone.

CO2: Second Chance is not for newbie board gamers. When my copy arrived in early February, it was at that point the most complicated game I had ever attempted to learn from a rulebook. Disaster management coops like Pandemic (2006) and Endangered are my jam, but initially CO2: Second Chance still intimidated the heck out of me. Learning how to read the game’s unique system of hieroglyphics was a challenge, for example.

I eventually turned to this helpful tutorial playthrough video from the invaluable Before You Play YouTube channel. Even once we were playing, the learning curve was steep. It took three attempts for us to even survive the first decade of the game’s five—on the third attempt, when we barely survived into the second decade. It felt like a huge accomplishment

Despite its difficulty, there’s something fundamentally sunny about CO2’s outlook. For one thing, it is built on the premise that energy corporations actually could and would cooperate to slow climate change, rather than actively work against it to protect their fossil fuel infrastructure and investments. As a gamer, I got really into it, but the environmental reporter part of my brain couldn’t quite suspend her disbelief. Even the fact that everyone at the beginning of the game agrees that high CO2 levels will end the game feels a bit unlike international energy corporations (even green ones).

“I’m a very optimistic person,” LaCerda told me, when I asked him about it. “I can see the future better than it is now.… It’s very rare for me to have a negative interaction [in my games.]”

That optimism is probably an asset, because it makes CO2: Second Chance feel more … well, fun, like a game. I’m glad it exists and is on my game shelf, but it also made me wonder what a more hard-nosed climate-themed cardboard opus would look like.

My favorite design decision in CO2: Second Chance is the secret individual goals given to each player at the start of the game. Coop games dominate the tabletop disaster-management field, but semi-cooperative games might be the tabletop genre that’s best suited to making a dent in the climate discourse. While coops can verge toward preachiness, semi-coops challenge each player to balance their individual goals with the shared interests of everyone at the table and achieve both. I wish that real-world climate action could resemble a fully cooperative game with everyone working together toward a shared goal, but real-world climate action is usually messy, requiring environmental advocates to navigate a multitude of stakeholder goals and (sometimes conflicting) values. Semi-coops often incorporate conflicting goals and different definitions of what a “win” looks like.

LaCerda designed the game so that players receive secret goals even when playing in “fully cooperative” mode. When I asked him why, he told me, “There is one problem in cooperative games called the "alpha problem." That is when one player tells everybody what they have to do.” By making individual goals private, any know-it-all player that might try to boss around other players is missing key pieces of information, so everyone can choose their own strategy

The alpha player problem in gaming has parallels in global action—or inaction on climate. Many people feel that there’s little they can do against a global problem, and so they often wait for powerful people, the ones who lead governments and corporations, to address the problem. But, of course, real life isn’t a cooperative game, and most of those powerful people have scant personal incentive to forestall disaster.

I don’t know if CO2 is a game that would change anyone’s mind on the importance of climate action; its marketing is squarely aimed at people who are already convinced that climate change is real. But I could see it being a game that motivates someone to call their elected representatives and demand that the government behave a little bit more like a player in a cooperative game.

I hope so, because, with climate change, it’s not just cardboard tokens and meeples on the line.

Closing Thoughts

Playing through all these games was a real treat. Every single one of them is a game that I want to play again. They’re loaded with cool ideas and beautiful art. Being able to look at my game shelf and see my personal interest in animals and ecosystems reflected back at me is awesome. Endangered in particular has become one of my absolute favorite board games.

I’d be psyched to see (and play) more climate-themed games in the next few years, though I wonder if game designers see enough of a market to keep creating new ones.

Crapuchettes has no such doubts. “You don’t want to say it’s a trend? I’ll say it’s a trend!" Tabletop gaming is growing as a hobby, he added, and still creating new market niches for games with all types of themes. Published board games often spend as much as three years in development, so most of the games on this list existed in prototype form long before Wingspan became a runaway hit.

In just the past three months, I have met half a dozen people on game design Discords who are working on environment-related games (and, yes, I have one too). Forthcoming projects from established designers, such as Matt Leacock’s climate-crisis-themed Daybreak and Keystone: North America by Isaac Vega and Jeffrey Joyce, are on the horizon. LaCerda will soon publish a game called Weather Machine, in which players must try to mitigate the damage caused when a mad scientist’s global climate-control device goes rogue. “It’s a fiction game, but it’s about the same problems that I have with the environment,” LaCerda says.

Will these games sell? Will they inspire more gamers to get involved in the real-world struggle against climate change? That’s less clear.

Fortunately, environmental communication is an active area of research. One study that I think has the most actionable advice for would-be climate game designers is “Effectiveness of gaming for communicating and teaching climate change,” published in the journal Climatic Change in 2018 by economists Klaus Eisenack and Jasper Meya. In the early 2000s, Eisenack, who is a board game enthusiast as well as an economist, adapted an “integrated assessment model” from his academic work on political and economic responses to climate change into a board game called Keep Cool (2004).

“It’s a bit like in the real world,” Meya says, of the game. “If you have a certain amount of economic growth—and you can choose whether you get to this with black factories that are carbon-emitting or green factories that are carbon neutral, so you as a player can decide which strategy you choose.… You can in principle win with both strategies. So you can see how the climate system reacts, how the other players react.… That way the player gets a feeling of why it is so difficult to get collective action on climate change mitigation.”

In the study, Eisenack and Meya played Keep Cool in classrooms several dozen times with German high school students. The students filled out surveys about their attitudes on climate change both before and after the game. After playing Keep Cool, the students were more confident that politicians could address climate change. Interestingly, students who played with a more “selfish” strategy of building carbon-emitting factories and letting other players deal with the fallout were more optimistic about international cooperation on climate change actually occurring. Eisenack and Meya concluded that games aiming to make players feel more invested in climate change can include non-cooperative mechanics. They even speculate that giving players a choice between “greener,” more altruistic strategies and more selfish, competitive options may actually strengthen climate games’ messages. The students also reported feeling more personal responsibility about climate change in the post-game surveys. “I really believe and also saw, when I played this game 60 times or so with high school students, that it’s very different from reading a text, because players, they want to win, they get annoyed, they get emotional,” Meya says.

Though it’s just one study, these results make sense to me: Games have a unique ability to put a person in someone else’s shoes and allow players to watch feedback loops and complex systems play out on the table in front of them. Games excel at making probabilistic events, chains of cause and effect, and the impacts of decisions feel accessible and concrete. These are areas where journalism and other forms of climate education often struggle.

That said, I’d encourage designers to get environmental reporters, activists, scientists, and local stakeholders to play-test their climate games! People who cover environmental issues are constantly thinking about how to balance the “doom and gloom” of climate change with empowering stories that motivate people to take action. That expertise is invaluable.

And I’d encourage game-players who want to see more ecologically themed games to speak up about it. Every single designer I interviewed for this article said they had to navigate a lot of skepticism to even get their games to market. Gamers spend lots of money on games with fantasy, sci-fi, and “Medieval Europe-ish” themes, and many publishers remain hesitant to deviate from a successful pattern. But if ecology-inflected games like Wingspan sell well and generate online buzz, that’s a sign to publishers that there’s a market out there for more like it.

Will any of that make a dent in the broader climate discourse? I’m not sure. My gut tells me that people who buy environmentally themed games already believe climate change is real, but tabletop games are played by groups. Tabletop games are nothing if not conversation-generators, and, if they show up at family and community game nights, discussions will happen. Some of those discussions might just keep climate and ecology in people’s minds in a problem-solving way. Others might persuade people to take action on climate. And a few might even change a few minds.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club